When former Superbowl quarterback Colin Kaepernick took a knee during the national anthem over a year ago, I don’t think anyone could have predicted what would happen next. Whether that would have been one of the singers of the anthem taking a knee a couple of weeks ago, a Houston high schooler sitting during the pledge of allegiance, or high school football players imitating professional ones, Kaepernick’s stance just keeps on giving.

Of course, the four African-American students deciding to sit-in at the Woolworth’s lunch counter in Greensboro, North Carolina, had no idea whether the time was ripe, or whether it wasn’t. They did it for the same reasons that Kaepernick did – because they had given up hope that anyone else would.

The “Greensboro Four” sparked other sit-ins that focused on a definite goal: changing the segregationist policies of Woolworth’s and the local ordinances that put the police in a position to enforce them. It’s unclear, however, where the NFL players’ actions will end up.

One thing it has done is show how little we know about this country’s treatment of protest and dissent. While the public discussion has overwhelmingly focused on protecting the players’ “right to protest” by taking a knee, the law is crystal clear on one point: professional football players are employees, and the football stadiums where they play are private workplaces. In that respect, there’s no difference between them and a secretary who works in an office. Either can be disciplined at will by the employer because the worker has no constitutional rights in the workplace.

As shocking as that may sound, that’s been the law in this country for over a century. When you work for a private company (and there’s no union contract that protects certain rights), the company’s rights in running the workplace supplant any constitutional rights that you have as a worker. It’s why your employer can read your e-mail at will (violating your privacy rights), can require drug/urine testing and locker searches (violating your privacy rights), and stop you from meeting with union organizers or hanging posters in the lunchroom (violating your First Amendment rights).

So, while we’re all talking about the “right” to take a knee, none of us are talking about the fact that the “right” doesn’t exist. NFL owners can discipline their players at will, because the players lose their constitutional rights when they walk into their locker room or onto the field. It’s why Jerry Jones, the owner of the Dallas Cowboys, recently threatened to bench any player that takes a knee during the anthem – because he legally can.

While we need to be supportive of protest and dissent efforts generally, that also means understanding that protest is less meaningful when it doesn’t result in forcing structural change.

It would be as if the sit-ins of the 1960’s contented themselves just with sitting over and over again, rather than leveraging those brave acts to change the system that legalized and enforced segregation.

Making change means more than limiting our horizons to just taking a knee. It means taking time to understand that the latitude to protest in the workplace in the United States today is only as broad as the employer allows; and that, as long as we accept that limitation, our protests will only be tolerated until they make our employers uncomfortable.

CELDF is working with communities and our statewide Community Rights Networks to advance systemic change. We are partnering together to elevate the rights of people, workers, communities, and nature, above the claimed rights of corporations and above state efforts to preempt our communities.

Your donation makes our work possible! Please donate today.

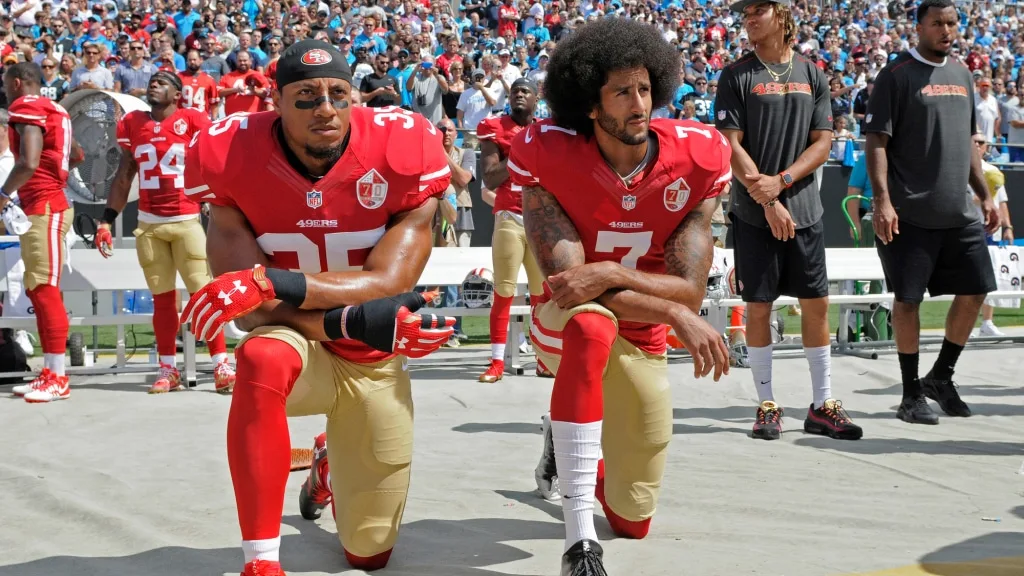

Featured image: Colin Kaepernick,Eric Reid / AP Photo by Mike McCarn

When former Superbowl quarterback Colin Kaepernick took a knee during the national anthem over a year ago, I don’t think anyone could have predicted what would happen next. Whether that would have been one of the singers of the anthem taking a knee a couple of weeks ago, a Houston high schooler sitting during the pledge of allegiance, or high school football players imitating professional ones, Kaepernick’s stance just keeps on giving.

Of course, the four African-American students deciding to sit-in at the Woolworth’s lunch counter in Greensboro, North Carolina, had no idea whether the time was ripe, or whether it wasn’t. They did it for the same reasons that Kaepernick did – because they had given up hope that anyone else would.

The “Greensboro Four” sparked other sit-ins that focused on a definite goal: changing the segregationist policies of Woolworth’s and the local ordinances that put the police in a position to enforce them. It’s unclear, however, where the NFL players’ actions will end up.

One thing it has done is show how little we know about this country’s treatment of protest and dissent. While the public discussion has overwhelmingly focused on protecting the players’ “right to protest” by taking a knee, the law is crystal clear on one point: professional football players are employees, and the football stadiums where they play are private workplaces. In that respect, there’s no difference between them and a secretary who works in an office. Either can be disciplined at will by the employer because the worker has no constitutional rights in the workplace.

As shocking as that may sound, that’s been the law in this country for over a century. When you work for a private company (and there’s no union contract that protects certain rights), the company’s rights in running the workplace supplant any constitutional rights that you have as a worker. It’s why your employer can read your e-mail at will (violating your privacy rights), can require drug/urine testing and locker searches (violating your privacy rights), and stop you from meeting with union organizers or hanging posters in the lunchroom (violating your First Amendment rights).

So, while we’re all talking about the “right” to take a knee, none of us are talking about the fact that the “right” doesn’t exist. NFL owners can discipline their players at will, because the players lose their constitutional rights when they walk into their locker room or onto the field. It’s why Jerry Jones, the owner of the Dallas Cowboys, recently threatened to bench any player that takes a knee during the anthem – because he legally can.

While we need to be supportive of protest and dissent efforts generally, that also means understanding that protest is less meaningful when it doesn’t result in forcing structural change.

It would be as if the sit-ins of the 1960’s contented themselves just with sitting over and over again, rather than leveraging those brave acts to change the system that legalized and enforced segregation.

Making change means more than limiting our horizons to just taking a knee. It means taking time to understand that the latitude to protest in the workplace in the United States today is only as broad as the employer allows; and that, as long as we accept that limitation, our protests will only be tolerated until they make our employers uncomfortable.

CELDF is working with communities and our statewide Community Rights Networks to advance systemic change. We are partnering together to elevate the rights of people, workers, communities, and nature, above the claimed rights of corporations and above state efforts to preempt our communities.

Your donation makes our work possible! Please donate today.

Featured image: Colin Kaepernick,Eric Reid / AP Photo by Mike McCarn

When former Superbowl quarterback Colin Kaepernick took a knee during the national anthem over a year ago, I don’t think anyone could have predicted what would happen next. Whether that would have been one of the singers of the anthem taking a knee a couple of weeks ago, a Houston high schooler sitting during the pledge of allegiance, or high school football players imitating professional ones, Kaepernick’s stance just keeps on giving.

Of course, the four African-American students deciding to sit-in at the Woolworth’s lunch counter in Greensboro, North Carolina, had no idea whether the time was ripe, or whether it wasn’t. They did it for the same reasons that Kaepernick did – because they had given up hope that anyone else would.

The “Greensboro Four” sparked other sit-ins that focused on a definite goal: changing the segregationist policies of Woolworth’s and the local ordinances that put the police in a position to enforce them. It’s unclear, however, where the NFL players’ actions will end up.

One thing it has done is show how little we know about this country’s treatment of protest and dissent. While the public discussion has overwhelmingly focused on protecting the players’ “right to protest” by taking a knee, the law is crystal clear on one point: professional football players are employees, and the football stadiums where they play are private workplaces. In that respect, there’s no difference between them and a secretary who works in an office. Either can be disciplined at will by the employer because the worker has no constitutional rights in the workplace.

As shocking as that may sound, that’s been the law in this country for over a century. When you work for a private company (and there’s no union contract that protects certain rights), the company’s rights in running the workplace supplant any constitutional rights that you have as a worker. It’s why your employer can read your e-mail at will (violating your privacy rights), can require drug/urine testing and locker searches (violating your privacy rights), and stop you from meeting with union organizers or hanging posters in the lunchroom (violating your First Amendment rights).

So, while we’re all talking about the “right” to take a knee, none of us are talking about the fact that the “right” doesn’t exist. NFL owners can discipline their players at will, because the players lose their constitutional rights when they walk into their locker room or onto the field. It’s why Jerry Jones, the owner of the Dallas Cowboys, recently threatened to bench any player that takes a knee during the anthem – because he legally can.

While we need to be supportive of protest and dissent efforts generally, that also means understanding that protest is less meaningful when it doesn’t result in forcing structural change.

It would be as if the sit-ins of the 1960’s contented themselves just with sitting over and over again, rather than leveraging those brave acts to change the system that legalized and enforced segregation.

Making change means more than limiting our horizons to just taking a knee. It means taking time to understand that the latitude to protest in the workplace in the United States today is only as broad as the employer allows; and that, as long as we accept that limitation, our protests will only be tolerated until they make our employers uncomfortable.

CELDF is working with communities and our statewide Community Rights Networks to advance systemic change. We are partnering together to elevate the rights of people, workers, communities, and nature, above the claimed rights of corporations and above state efforts to preempt our communities.

Your donation makes our work possible! Please donate today.

Featured image: Colin Kaepernick,Eric Reid / AP Photo by Mike McCarn

When former Superbowl quarterback Colin Kaepernick took a knee during the national anthem over a year ago, I don’t think anyone could have predicted what would happen next. Whether that would have been one of the singers of the anthem taking a knee a couple of weeks ago, a Houston high schooler sitting during the pledge of allegiance, or high school football players imitating professional ones, Kaepernick’s stance just keeps on giving.

Of course, the four African-American students deciding to sit-in at the Woolworth’s lunch counter in Greensboro, North Carolina, had no idea whether the time was ripe, or whether it wasn’t. They did it for the same reasons that Kaepernick did – because they had given up hope that anyone else would.

The “Greensboro Four” sparked other sit-ins that focused on a definite goal: changing the segregationist policies of Woolworth’s and the local ordinances that put the police in a position to enforce them. It’s unclear, however, where the NFL players’ actions will end up.

One thing it has done is show how little we know about this country’s treatment of protest and dissent. While the public discussion has overwhelmingly focused on protecting the players’ “right to protest” by taking a knee, the law is crystal clear on one point: professional football players are employees, and the football stadiums where they play are private workplaces. In that respect, there’s no difference between them and a secretary who works in an office. Either can be disciplined at will by the employer because the worker has no constitutional rights in the workplace.

As shocking as that may sound, that’s been the law in this country for over a century. When you work for a private company (and there’s no union contract that protects certain rights), the company’s rights in running the workplace supplant any constitutional rights that you have as a worker. It’s why your employer can read your e-mail at will (violating your privacy rights), can require drug/urine testing and locker searches (violating your privacy rights), and stop you from meeting with union organizers or hanging posters in the lunchroom (violating your First Amendment rights).

So, while we’re all talking about the “right” to take a knee, none of us are talking about the fact that the “right” doesn’t exist. NFL owners can discipline their players at will, because the players lose their constitutional rights when they walk into their locker room or onto the field. It’s why Jerry Jones, the owner of the Dallas Cowboys, recently threatened to bench any player that takes a knee during the anthem – because he legally can.

While we need to be supportive of protest and dissent efforts generally, that also means understanding that protest is less meaningful when it doesn’t result in forcing structural change.

It would be as if the sit-ins of the 1960’s contented themselves just with sitting over and over again, rather than leveraging those brave acts to change the system that legalized and enforced segregation.

Making change means more than limiting our horizons to just taking a knee. It means taking time to understand that the latitude to protest in the workplace in the United States today is only as broad as the employer allows; and that, as long as we accept that limitation, our protests will only be tolerated until they make our employers uncomfortable.

CELDF is working with communities and our statewide Community Rights Networks to advance systemic change. We are partnering together to elevate the rights of people, workers, communities, and nature, above the claimed rights of corporations and above state efforts to preempt our communities.

Your donation makes our work possible! Please donate today.

Featured image: Colin Kaepernick,Eric Reid / AP Photo by Mike McCarn

When former Superbowl quarterback Colin Kaepernick took a knee during the national anthem over a year ago, I don’t think anyone could have predicted what would happen next. Whether that would have been one of the singers of the anthem taking a knee a couple of weeks ago, a Houston high schooler sitting during the pledge of allegiance, or high school football players imitating professional ones, Kaepernick’s stance just keeps on giving.

Of course, the four African-American students deciding to sit-in at the Woolworth’s lunch counter in Greensboro, North Carolina, had no idea whether the time was ripe, or whether it wasn’t. They did it for the same reasons that Kaepernick did – because they had given up hope that anyone else would.

The “Greensboro Four” sparked other sit-ins that focused on a definite goal: changing the segregationist policies of Woolworth’s and the local ordinances that put the police in a position to enforce them. It’s unclear, however, where the NFL players’ actions will end up.

One thing it has done is show how little we know about this country’s treatment of protest and dissent. While the public discussion has overwhelmingly focused on protecting the players’ “right to protest” by taking a knee, the law is crystal clear on one point: professional football players are employees, and the football stadiums where they play are private workplaces. In that respect, there’s no difference between them and a secretary who works in an office. Either can be disciplined at will by the employer because the worker has no constitutional rights in the workplace.

As shocking as that may sound, that’s been the law in this country for over a century. When you work for a private company (and there’s no union contract that protects certain rights), the company’s rights in running the workplace supplant any constitutional rights that you have as a worker. It’s why your employer can read your e-mail at will (violating your privacy rights), can require drug/urine testing and locker searches (violating your privacy rights), and stop you from meeting with union organizers or hanging posters in the lunchroom (violating your First Amendment rights).

So, while we’re all talking about the “right” to take a knee, none of us are talking about the fact that the “right” doesn’t exist. NFL owners can discipline their players at will, because the players lose their constitutional rights when they walk into their locker room or onto the field. It’s why Jerry Jones, the owner of the Dallas Cowboys, recently threatened to bench any player that takes a knee during the anthem – because he legally can.

While we need to be supportive of protest and dissent efforts generally, that also means understanding that protest is less meaningful when it doesn’t result in forcing structural change.

It would be as if the sit-ins of the 1960’s contented themselves just with sitting over and over again, rather than leveraging those brave acts to change the system that legalized and enforced segregation.

Making change means more than limiting our horizons to just taking a knee. It means taking time to understand that the latitude to protest in the workplace in the United States today is only as broad as the employer allows; and that, as long as we accept that limitation, our protests will only be tolerated until they make our employers uncomfortable.

CELDF is working with communities and our statewide Community Rights Networks to advance systemic change. We are partnering together to elevate the rights of people, workers, communities, and nature, above the claimed rights of corporations and above state efforts to preempt our communities.

Your donation makes our work possible! Please donate today.

Featured image: Colin Kaepernick,Eric Reid / AP Photo by Mike McCarn

When former Superbowl quarterback Colin Kaepernick took a knee during the national anthem over a year ago, I don’t think anyone could have predicted what would happen next. Whether that would have been one of the singers of the anthem taking a knee a couple of weeks ago, a Houston high schooler sitting during the pledge of allegiance, or high school football players imitating professional ones, Kaepernick’s stance just keeps on giving.

Of course, the four African-American students deciding to sit-in at the Woolworth’s lunch counter in Greensboro, North Carolina, had no idea whether the time was ripe, or whether it wasn’t. They did it for the same reasons that Kaepernick did – because they had given up hope that anyone else would.

The “Greensboro Four” sparked other sit-ins that focused on a definite goal: changing the segregationist policies of Woolworth’s and the local ordinances that put the police in a position to enforce them. It’s unclear, however, where the NFL players’ actions will end up.

One thing it has done is show how little we know about this country’s treatment of protest and dissent. While the public discussion has overwhelmingly focused on protecting the players’ “right to protest” by taking a knee, the law is crystal clear on one point: professional football players are employees, and the football stadiums where they play are private workplaces. In that respect, there’s no difference between them and a secretary who works in an office. Either can be disciplined at will by the employer because the worker has no constitutional rights in the workplace.

As shocking as that may sound, that’s been the law in this country for over a century. When you work for a private company (and there’s no union contract that protects certain rights), the company’s rights in running the workplace supplant any constitutional rights that you have as a worker. It’s why your employer can read your e-mail at will (violating your privacy rights), can require drug/urine testing and locker searches (violating your privacy rights), and stop you from meeting with union organizers or hanging posters in the lunchroom (violating your First Amendment rights).

So, while we’re all talking about the “right” to take a knee, none of us are talking about the fact that the “right” doesn’t exist. NFL owners can discipline their players at will, because the players lose their constitutional rights when they walk into their locker room or onto the field. It’s why Jerry Jones, the owner of the Dallas Cowboys, recently threatened to bench any player that takes a knee during the anthem – because he legally can.

While we need to be supportive of protest and dissent efforts generally, that also means understanding that protest is less meaningful when it doesn’t result in forcing structural change.

It would be as if the sit-ins of the 1960’s contented themselves just with sitting over and over again, rather than leveraging those brave acts to change the system that legalized and enforced segregation.

Making change means more than limiting our horizons to just taking a knee. It means taking time to understand that the latitude to protest in the workplace in the United States today is only as broad as the employer allows; and that, as long as we accept that limitation, our protests will only be tolerated until they make our employers uncomfortable.

CELDF is working with communities and our statewide Community Rights Networks to advance systemic change. We are partnering together to elevate the rights of people, workers, communities, and nature, above the claimed rights of corporations and above state efforts to preempt our communities.

Your donation makes our work possible! Please donate today.

Featured image: Colin Kaepernick,Eric Reid / AP Photo by Mike McCarn

When former Superbowl quarterback Colin Kaepernick took a knee during the national anthem over a year ago, I don’t think anyone could have predicted what would happen next. Whether that would have been one of the singers of the anthem taking a knee a couple of weeks ago, a Houston high schooler sitting during the pledge of allegiance, or high school football players imitating professional ones, Kaepernick’s stance just keeps on giving.

Of course, the four African-American students deciding to sit-in at the Woolworth’s lunch counter in Greensboro, North Carolina, had no idea whether the time was ripe, or whether it wasn’t. They did it for the same reasons that Kaepernick did – because they had given up hope that anyone else would.

The “Greensboro Four” sparked other sit-ins that focused on a definite goal: changing the segregationist policies of Woolworth’s and the local ordinances that put the police in a position to enforce them. It’s unclear, however, where the NFL players’ actions will end up.

One thing it has done is show how little we know about this country’s treatment of protest and dissent. While the public discussion has overwhelmingly focused on protecting the players’ “right to protest” by taking a knee, the law is crystal clear on one point: professional football players are employees, and the football stadiums where they play are private workplaces. In that respect, there’s no difference between them and a secretary who works in an office. Either can be disciplined at will by the employer because the worker has no constitutional rights in the workplace.

As shocking as that may sound, that’s been the law in this country for over a century. When you work for a private company (and there’s no union contract that protects certain rights), the company’s rights in running the workplace supplant any constitutional rights that you have as a worker. It’s why your employer can read your e-mail at will (violating your privacy rights), can require drug/urine testing and locker searches (violating your privacy rights), and stop you from meeting with union organizers or hanging posters in the lunchroom (violating your First Amendment rights).

So, while we’re all talking about the “right” to take a knee, none of us are talking about the fact that the “right” doesn’t exist. NFL owners can discipline their players at will, because the players lose their constitutional rights when they walk into their locker room or onto the field. It’s why Jerry Jones, the owner of the Dallas Cowboys, recently threatened to bench any player that takes a knee during the anthem – because he legally can.

While we need to be supportive of protest and dissent efforts generally, that also means understanding that protest is less meaningful when it doesn’t result in forcing structural change.

It would be as if the sit-ins of the 1960’s contented themselves just with sitting over and over again, rather than leveraging those brave acts to change the system that legalized and enforced segregation.

Making change means more than limiting our horizons to just taking a knee. It means taking time to understand that the latitude to protest in the workplace in the United States today is only as broad as the employer allows; and that, as long as we accept that limitation, our protests will only be tolerated until they make our employers uncomfortable.

CELDF is working with communities and our statewide Community Rights Networks to advance systemic change. We are partnering together to elevate the rights of people, workers, communities, and nature, above the claimed rights of corporations and above state efforts to preempt our communities.

Your donation makes our work possible! Please donate today.

Featured image: Colin Kaepernick,Eric Reid / AP Photo by Mike McCarn