On July 21st, a special live streaming event will bring together grassroots activists from these places to share their experiences of repression and resistance. The event,…

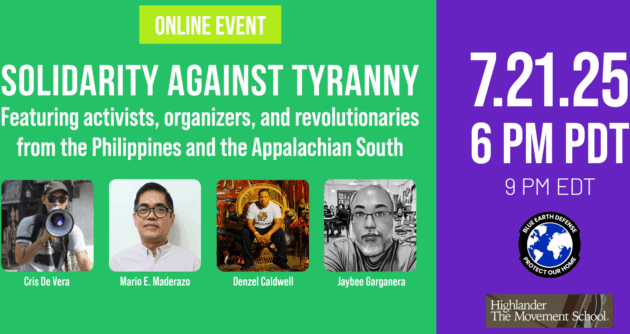

On July 21st, a special live streaming event will bring together grassroots activists from these places to share their experiences of repression and resistance. The event, called “Solidarity Against Tyranny,” begins at 6pm Pacific Daylight Time (aka 9pm Eastern Daylight Time, or 9am on July 22nd, Philippine Time) and is free to attend.

On July 21st, a special live streaming event will bring together grassroots activists from these places to share their experiences of repression and resistance. The event,…

On July 21st at 6pm PDT / 9pm EDT, we invite you to join us for a special event, “Solidarity Against Tyranny,” to help answer…

COLUMBUS, OH – What can a community do when the democratic process itself has been outlawed? That’s the question facing residents of Ohio.

Contact: Tish O’Dell, CELDF Consulting Director Tish@CELDF.org 440-552-6774 For Immediate Release A collection of essays that confront the root causes of the interconnected ecological and…

Announcing Truth and Reckoning on Substack, a project of the Community Environmental Legal Defense Fund (CELDF). We’re launching this Substack newsletter as we celebrate our…

Can You Handle the Truth? – Essays of Hard Truths Aimed at Right Relationship with Earth and Each Other Can You Handle the Truth? is…

Feature photo by Pax Ahimsa Gethen We are long past the time when we can afford to settle for Pyrrhic victories Despite growing awareness of…

There is a critical need for a movement to recognize nature as a legal entity with rights. Just as human rights are enshrined in law…

Dozens of activists for the rights of nature who traveled to the United Nations to participate in a high-level meeting were unexpectedly barred from speaking…

Regional environmental leader Tish O’Dell spoke to Cleveland State students about the legal system’s failure to protect nature and the urgent need for cultural change.

Grant Township’s 2014 Rights of Nature law became the first such piece of legislation to be enforced by a state, with the Pennsylvania Department of…

Today, April 22nd (Earth Day), advocates for the New York bill have been invited to the United Nations to address a high-level meeting on harmony…

Voluntary standards for light pollution, like voluntary standards for much else where profit and community or ecosystem well-being might be at odds, have a habit…

This interview was conducted by the Environmental Coffeehouse welcoming Ben Price, CELDF Education Director & Tish O’Dell, Consulting Director of Community Environmental Legal Defense Fund…

In the first part of the program, author and Community Environmental Legal Defense Fund’s education director Ben Price joins the program to talk about his…

“Great Lakes and State Waters Bill of Rights” introduced in New York State Assembly BUFFALO – What if bodies of water were guaranteed the kinds of…

Author, Ben Price, was interviewed on the Project Censored Show by Eleanor Goldfield about his new book, Wouldn’t You Say, A Collection of Essays on Environment…

We hope you enjoy the articles, factoids, features, and spotlights of the people who make CELDF the powerhouse that it is through our 2024 End-of-Year Newsletter.

Summer is fading away. School is back in full swing. Electoral politics are in full volume. And, 2024 is fast approaching its end. CELDF’s 2024 “Vote…

The essays in Wouldn’t You Say? ask challenging questions about modern society, our relationship to each other, and to the natural world. Order Your Copy…

Feature photo by Samuel Regan-Asante on Unsplash Opposing harmful industrial projects – like mines, aerial pesticide spraying, factory farms, or toxic waste disposal facilities – is…