Written by Taru Taylor

Boycott

Half a decade ago I boycotted my law-school graduation ceremony. Case Western Reserve University (CWRU) had recycled a photo of me for one of its “diversity” advertisements, without my permission. I was thus tokenized as an “underrepresented minority.”

This experience almost defeated my purpose for attending CWRU in the first place. For I was determined to go where my LSAT score (law school admissions test) matched the school average. I took “meritocracy” seriously. I never wanted to go through the back door as a “minority.”

One CWRU law professor who’s white and liberal told me that my boycott was an “overreaction” to an “honest mistake.” A Black civil rights attorney and fellow law-school alumna said that although she understood where I was coming from, she “would’ve handled it differently.” My protest got some support from a handful of professors, students, alumni and alumnae. But the overall campus vibe was that I’d made a mountain out of a “microaggression.”

Petition

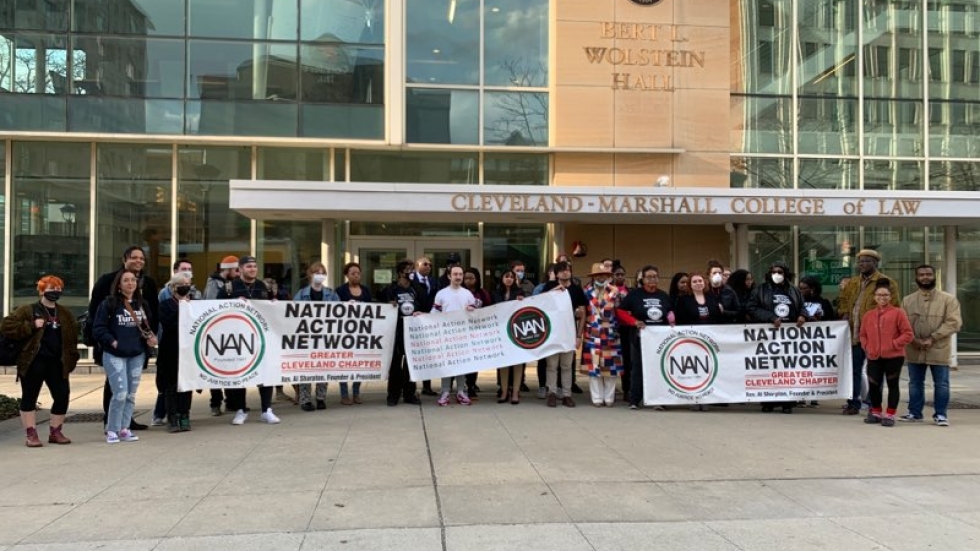

Fast forward to fall 2020, just a few months after the George Floyd tragedy. Local community stakeholders petitioned Cleveland State University (CSU) to take down the name “John Marshall” from its law school. I drafted the petition after reading Paul Finkelman’s Supreme Injustice, especially its chapter on Marshall’s proslavery judging and slaveholding. But what jump-started my efforts was a previous petition drafted by Hanna Kassis, an alumnus of the University of Illinois College of Law who successfully led the fight to rename his alma mater. The CSU board of trustees did finally expunge “Marshall” last November 17, 2022.

Cue outraged reaction from the right. One CSU alumnus’ letter to the editor blamed the decision on the “woke crowd” and on “current Bolsheviks of thought.” The Kwarcianys’ letter epitomizes the paranoid style which frames any fight against institutional racism as “cancel culture” run amok.

As if canceling white supremacy were a bad thing.

Badges and incidents of slavery

We’re now in 2023, the third year of the George Floyd era. It also marks the fifty-fifth anniversary of the assassinations of Martin Luther King Jr. and Robert Kennedy. Zoom out and it’s 531 years since Christopher Columbus set foot on American soil. Zoom in and I will have lived in Cleveland for eight years come August.

My law-school experiences typify the U.S. problem of internal colonialism. That is, historian and former Ebony editor Lerone Bennett Jr.’s idea that white colonizers and colonized Blacks underpin U.S. demographics. No American city better fits the profile of Blacks segregated in poverty amidst white suburban affluence. Cleveland is where Third-World conditions meet “First-World problems.”

Cleveland thus provides the backdrop for this essay on badges and incidents of slavery. I started off this essay by narrating two of my racist experiences while living here. I will use the concept of internal colonialism to explain why they were badges and incidents of slavery. This legal term of art denotes the Thirteenth Amendment, which gave Congress the power to abolish slavery and its badges and incidents.

Internal colonialism

The marketing ad that used my Black face in the name of “diversity” was not a “microaggression.” The campaign to take down a judicial icon of the antebellum slave power was not “cancel culture.” Understand: these were badges and incidents of slavery.

In Jones v. Alfred H. Mayer Co. (1968), the Supreme Court held: “Congress has the power under the Thirteenth Amendment rationally to determine what are the badges and incidents of slavery, and the authority to translate that determination into effective legislation.” And so, it behooves American citizens who are Black to define badges and incidents of slavery in our own terms. To inform public opinion; to instruct 535 U.S. congressmen and congresswomen to legislate thereby. Especially, the Congressional Black Caucus.

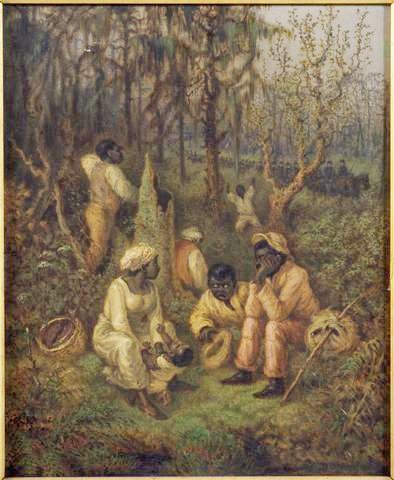

Our definition starts with the fact that Black Americans are here because so many of our ancestors were kidnapped from Africa; trafficked across the Atlantic; enslaved in the Americas. Our very presence in the Western Hemisphere is an incident of slavery. Our Black skin was arbitrarily attainted into a badge of slavery.

The U.S. ruling class that dates from the 1606 founding of the Virginia Company eventually forced Blacks into hereditary servitude, even as they coerced many of their fellow Europeans into indentured servitude. Each of our country’s original 13 colonies fit the pattern of European exploitation of American Indians, Irish Catholics, and Africans.

We should therefore define badges and incidents of slavery within the context of Lerone Bennett Jr.’s essay on internal colonialism titled “System.” Every colonial system is based on a relationship of dominance and subordination. The European system resulted from the slave trade and military conquest. He defines colonialism as: “a mass relationship of economic exploitation based on inequality and contempt and perpetrated by force, cultural repression, and the political ideology of racism.”

Bennett refers to the U.S. variant as internal colonialism. Its demography scans a white developing center and a Black underdeveloped circumference—white suburban enclaves and Black inner-city ghettos. The Black-bourgeois class mediates between the white center and the Black circumference. “What Britain was to Ghana, what France was to Senegal, white America was (and is) to the Black colony of America.”

But Bennett’s main point is that racism isn’t personal. It’s institutional. The question of white personal prejudice doesn’t matter. Black-bourgeois mediation doesn’t matter either. Racism holistically maintains white dominance and Black subordination through interlocking institutions. “The system is a synthesis of individual acts and institutionalized practices. Programmed by socioeconomic arrangements and propelled by the feedback of past and present exploitation, the system produces racist results from actions that may not be consciously racist.” [my italics]

Therefore, badges and incidents of slavery are racist results some 400 years in the making. They are institutional, not personal.

The boycott and the petition as badges and incidents of slavery

One of the administrators who was involved in the “diversity” ad summoned me to her office shortly after my op-ed explaining my boycott appeared in print. She told me that she felt personally attacked. She was on the brink of tears as she explained that my article’s conclusion—“I am not your Negro”—hurt her feelings. She felt like those words were directed at her.

But by making it all about her feelings, she missed the point of my protest. A protest that was so important to me that I denied my mother the opportunity to watch her son walk across the stage to receive my diploma. My fight was against institutional racism. Her feelings were beside the point. (What about my feelings?)

CWRU had exploited me as a marketing tool. Nor was any payment for my unwitting service forthcoming. Moreover, my alma mater labeled me as a so-called “underrepresented minority,” as if my place in the school weren’t merited. Unjust enrichment resulted whereby a white institution benefited at the expense of a Black man. The marketing ad was therefore an incident of slavery.

“John Marshall”—badge of slavery—is the easier argument. The man owned hundreds of slaves. One of my op-eds thus argued that his name was a proslavery symbol just as inflammatory as the Confederate battle flag. It parallels law professor Alexander Tsesis’ argument that Confederate monuments are badges of slavery. He argues that people should use the Thirteenth-Amendment ban against badges of slavery, as needed, to demolish racist monuments.

“These monuments commemorate the achievements of military prowess in support of slavery. They are not solely historical markers nor burial obelisks but symbols of racist heritage.” We Clevelanders petitioned CSU to expunge a name that commemorated judicial achievement in support of slavery. We helped take down a badge of slavery.

Conclusion

American Revolutionaries led by Benjamin Franklin and George Washington defeated King George III. In the words of The Declaration of Independence, they won a “separate and equal station.” They leveled up by way of the “Laws of Nature.” And by way of the self-evident truths that “all men are created equal” and governments derive “their just powers from the consent of the governed.” They pitted natural rights against the divine right of kings.

But white America pretends to what Bennett describes as the “divine right to appropriate the services and resources of the colonized.” They have hypocritically kept natural-law doctrine away from Blacks. They refuse to acknowledge natural rights with reference to Blacks.

The Dred Scott decision of 1857 expressed their controlling idea: “the negro had no rights which the white man was bound to respect.” Then, after the Civil War ended in 1865, they instituted Jim Crow. In other words, they segregated Blacks into a colonial situation. The “separate but equal” doctrine of Plessy v. Ferguson (1896) persists.

We must understand badges and incidents of slavery within this historical context. The colonial relationship of white dominance and Black subordination does change from time to time. The Supreme Court said as much, in Jones v. Alfred H. Mayer Co., when it described the Black Codes as substitutes for the slave system. In turn, “the exclusion of Negroes from white communities became a substitute for the Black Codes.” And so on.

The challenge: How to overcome the white dominance/Black subordination relationship. How to decolonize.

How to fight badges and incidents of slavery, but not petty-like as in a game of whack-a-mole. How to fight racist results, not personal prejudices. How to overcome racist institutions.

In short, how to level up to parity within the “new world order.”

We Blacks must embrace natural law. Become human-rights advocates in the spirit of Malcolm X. But we must do so in corporate terms. Our fight is against institutional racism, therefore we must build institutions. We have been subordinated as a group, therefore we must uplift ourselves as a group. We have been oppressed as Negroes; we must overcome as Maroons.

The posting of this piece is a reflection of CELDF’s commitment to featuring diverse perspectives and ideas in the quest to bring about a community rights and rights of nature existence into full being.

Author’s Note: I went to law school to learn all about how We the People are sovereign and how as jurors and electors we “check and balance” the other three branches of government. A lot of this stuff I should have learned in grade school. Please email me at tytaylor521@yahoo.com with questions or comments or further dialogue.