Written by Russell Weaver

Victory, Backlash, and Lessons for Community Rights in Buffalo, NY

Buffalo, New York is the state’s second largest municipality and one of the most impoverished, racially segregated cities in the country. Its scars from an extractive, post-industrial economy are on full display. In 2021 it came within inches of electing a community rights mayor who promised to “draw power down” to ordinary, working-class people through bold structural changes. That would-be mayor, Democratic nominee India Walton, lost the November general election to four-term incumbent, Byron Brown, who stayed in the race as a write-in candidate after Walton defeated him in the June primary.

The movement that Walton came from and built on isn’t about to vanish. Although it might experience some attrition, as all movements do after setbacks, the energy she helped channel within it remains a powerful force for radical change. Wielding that power in the days and years ahead will mean learning from Walton’s loss and identifying new targets, strategies, and tactics for prioritizing community rights in Buffalo. To aid those exercises, this article presents a condensed retelling of the mayoral race using the five “key lessons from past people’s movements” – published in the Community Environmental Legal Defense Fund’s (CELDF) 2015 pamphlet On Community Civil Disobedience in the Name of Sustainability – as an organizing framework. What emerges is a sentiment that, despite any deflating feelings that might accompany Walton’s general election loss, Buffalo’s capacity to build dual power – to truly “draw power down” to the people in a way that will put collective community needs ahead of ruling class profits – is arguably greater than ever.

Lesson 1: Movements start locally, with people who are personally harmed by existing systems

For readers unfamiliar with Buffalo, JoAnn Wypijeski’s pre-general election article in The Nation on the recent, post-1990s history of the city’s progressive movement provides critical context for how and why India Walton’s candidacy came to be. Consistent with CELDF’s analysis, people who were personally harmed by Buffalo’s legacies of redlining and disinvestment, industrial pollution, and, more recently, gentrification, formed organizations like PUSH Buffalo, the Partnership for the Public Good, the Clean Air Coalition, Grassroots Gardens, and numerous others – as well as mutual aid networks to fill gaps in public services – that advance social, racial, and economic justice at various spatial scales.

Walton, who grew up poor on Buffalo’s east side, and who left high school early after giving birth to her first child at the age of 14, was drawn into the world of politics through her personal experiences with struggle and perseverance. She was food insecure as a child, lived in a group home as a teenage mother, carted three children on and off the city’s neglected public transit infrastructure, and was subjected to racial discrimination within the health system her twins depended on. Walton’s eyes were opened early to the ways in which prevailing policies and institutions create and widen social inequalities.

At first, she fought against and resisted those systems as an individual. Citing the disrespect she’d felt during her twins’ hospital care, she returned to school to get her GED, and, later, a nursing degree, which she used to secure a job in the same children’s hospital that had previously felt so unwelcoming. When she began attending meetings and actions sponsored by Buffalo’s growing constellation of progressive organizations in the 2010s, her resistance became more firmly grounded in collective action. She eventually completed an Emerging Leaders program through Open Buffalo and dedicated herself to community organizing. She left her nursing job to co-found a Community Land Trust (CLT) in the Fruit Belt neighborhood of Buffalo.

The Fruit Belt is a historically African American, working-class neighborhood east of the city’s Main Street “dividing line.” A little over a decade ago, it became a hotbed for gentrification when billions of public dollars were leveraged to create the Buffalo Niagara Medical Campus (BNMC) on its doorstep. As a registered nurse who was living near and working at the medical campus, Walton acknowledges that she played an unwitting part in the gentrification pressures that BNMC created. But, between her own struggles with poverty and her increasingly clear analysis of social injustices, she was determined to fight back. She staged a one-woman protest that helped reserve street parking for community residents who were losing their spots to BNMC workers, and embraced her role as the first Executive Director of the Fruit Belt CLT.

A CLT is a mechanism for collectivizing land ownership and preserving housing affordability. Often a nonprofit organization controlled by community residents, a CLT holds land in trust within a geographic neighborhood. Structures sitting on that land can still be bought and sold using more conventional housing market mechanisms, but, by taking land out of the equation – i.e., homebuyers purchase structures only, not land – CLTs lower the cost of homebuying. These tools – collective land ownership and deed restrictions to eliminate property speculation – extend ownership and rental opportunities to lower income households and make affordability permanent. A CLT is therefore an institution for protecting community rights to collectively control land and how it is used in a neighborhood.

After declaring her candidacy for Mayor in the closing days of December 2020, Walton hit the campaign trail with a bold vision for scaling up local solutions like CLTs.

In addition to CLTs, Walton also proposed participatory budgeting (PB) to enable community residents to pitch and then vote on ways to use public funds; a municipal bank to provide non-extractive financing for community-anchored projects that could include democratically-owned and -controlled businesses; and an amendment to the city charter that would establish a host of sweeping protections for tenants. She also flirted with even deeper structural changes.

Around the time she announced her candidacy, I published a proposal to use Buffalo’s municipal Home Rule powers under the state constitution to form a charter commission, engage in extensive localized public education and organize around community rights. The goal was to rewrite – and, with hard work and organizing, vote to adopt – a rights-based charter to assert powers needed to control land use and protect environmental rights, worker rights, democratic rights, and rights of nature in neighborhoods. The city’s daily newspaper ran an op-ed on that proposal a few weeks later, which Walton shared on social media, hinting at her support for it.

Lesson 2: Movements move slowly

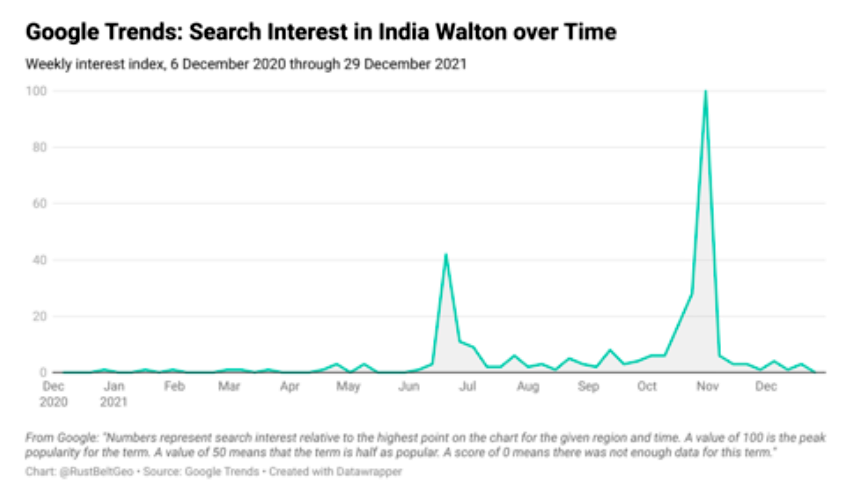

Mirroring the city’s broader progressive movement, Walton’s campaign operated mostly outside the mainstream’s view, plausibly creating perceptions among those not on her team that her candidacy wasn’t going anywhere. Although it’s just one indicator, the graph below shows the Google Trends search interest index for India Walton from the time she announced her candidacy to the present. Except for a few minor blips in the first five months of 2021, the graph suggests that most of the world didn’t take notice of Walton until the June Democratic primary.

Image Text: Google Trends: Search Interest in India Walton over Time; Weekly interest index, 6 December 2020 through 29 December 2021; From Google: ‘Numbers represent search interest relative to the highest point on the chart for the given region and time. A value of 100 is the peak popularity for the term. A value of 50 means that the term is half as popular. A score of 0 means that there was not enough data for this term.’ Chart by @RustBeltGeo

When she upset Brown in the primary, she shocked the Buffalo political establishment and, perhaps, the nation. The only people who weren’t surprised were Walton and her team. For months, they slowly and steadily logged long hours and late nights planning, door-knocking, making phone calls, and generally spreading a message of hope for a Buffalo that cares and works for all its residents.

By refusing to even acknowledge Walton or mention her name, let alone respond to her multiple requests for a pre-primary debate, Brown and his (over)confidence lulled much of the rest of the city into an electoral slumber. Brown’s victory in the primary was a foregone conclusion. Only it didn’t happen that way.

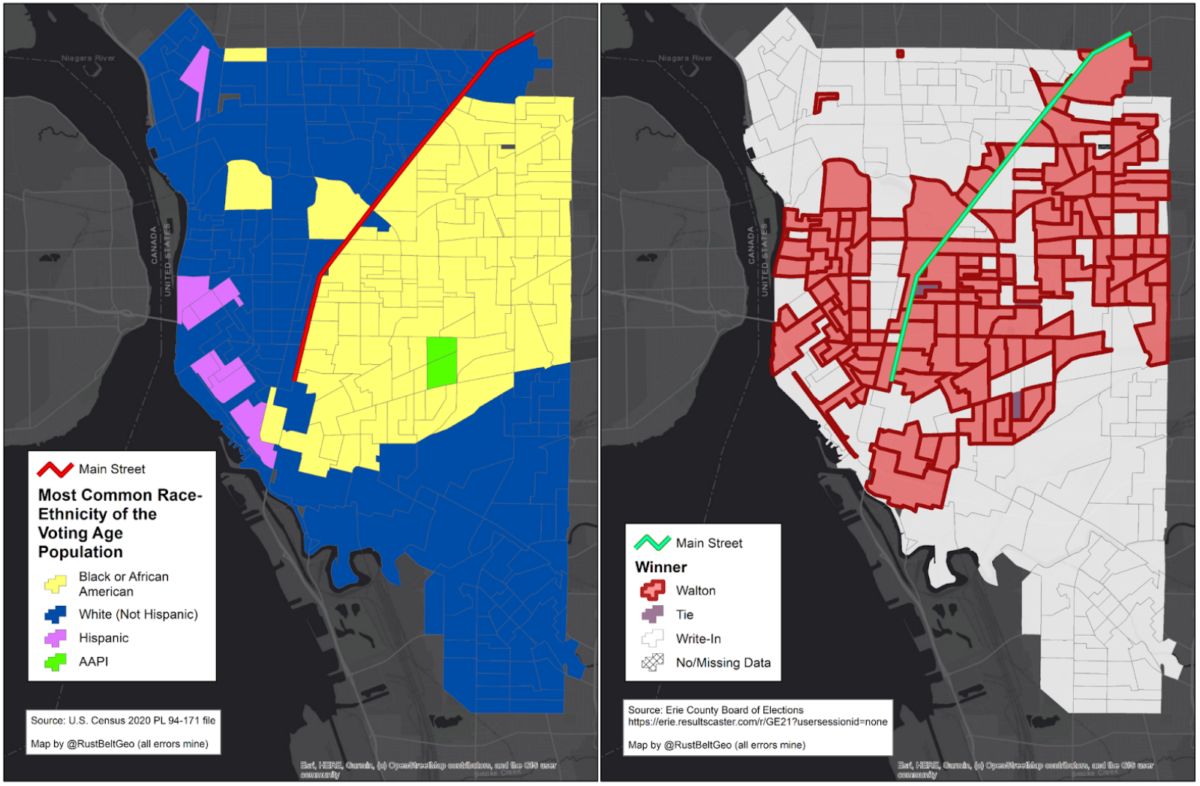

Notably, she carried more affluent, whiter neighborhoods in June while losing in working class communities of color; but in November those patterns were inverted. (See below map showing which precincts Walton won in November.)

Lesson 3: People who fight for fundamental change are ridiculed

As CELDF’s analysis of past people’s movements would have predicted, defenders of the status quo – and, presumably, its uneven distributions of wealth and power – were quick to wage personal attacks on Walton. Borrowing CELDF’s words, she was painted as too “radical, [her] ideas were ridiculed, and even [people] who sympathize with [her] cause argue[d] that the changes [she] seek[s] are too big” or too soon.

Brown’s incumbency, well-stocked campaign finance account, growth-friendly politics, and networked power allowed him to dominate headlines and control messaging after he lost the primary. The national media watchdog group FAIR put out a scathing post-election analysis in November that documented ways in which the local media, particularly the daily newspaper, reported on unverified talking points from Brown loyalists that actively sabotaged Walton’s public image. As Branko Marcetic put it in Jacobin, “Brown successfully turned the election debate to the petty personal mistakes of Walton…[and] it worked: a week before election day [in November], more than half of voters said their opinion of Walton had gotten worse since the primary.”

That turn of public opinion proved fatal to Walton’s campaign.

Lesson 4: Movements experience setbacks

Running parallel to the smear campaign targeting Walton was a coalition built by Brown. Unlike Walton, who strives to meet ordinary people where they are and bring them into a base of working-class power, Brown’s campaign catered to the already powerful. Brown conspired with establishment Democrats, millionaire developers, prominent Republicans and Republican financers, and the city’s formidable police union to consistently add fuel to the anti-Walton fires burning in the local news media.

Brown’s willingness to court and take large donations from Republicans came as a surprise to some, insofar as Brown is a lifelong Democrat and former Chair of the State Democratic Party. However, the move is far less surprising when viewed through the lens of working-class people collectively challenging the ruling class. In Pedagogy of the Oppressed, Paulo Freire cautions that:

“The elites call for harmony between classes as if classes were fortuitous agglomerations of individuals curiously looking at a shop window on a Sunday afternoon. [But] The only [real] harmony…is that found among the oppressors themselves. Although they may diverge and upon occasion even clash over group interests, they unite immediately at a threat to the class.”

Brown’s well-funded campaign of scare tactics and misinformation harmed Walton’s image with voters and mobilized support against her.

The election chapter of the story is over – it’s part of the past, another data point to be integrated into future analyses.

Yet, how the story develops in its next chapter is unwritten. Here’s where CELDF’s lessons can come into play. The important thing for Walton’s organization to do now is to reframe her loss not as an end, but “as a means to attain long-term structural change.” By the time of the general election, Walton’s base had become a multiracial, working-class bloc that transcended the city’s “Main Street dividing line” in ways that haven’t been seen in prior citywide elections. The seeds of collective “people power” in Buffalo seem to be sprouting.

Lesson 5: Creating systems change requires direct action

If elected, Walton may well have established the mechanisms she championed to prioritize community rights in Buffalo. But, without robust civic infrastructure in place to make full use of those mechanisms, any executive-level changes Walton could have made would still have had limited range. Put another way, systems change doesn’t hinge on electing the right candidate – it’s advanced most forcefully when organized communities engage in direct action.

Before the Buffalo mayoral election, one of the most common refrains about leftist candidates for major offices was that they mostly only win educated white voters. Their embrace of “socialist” policies, it’s been argued, doesn’t appeal to working class communities and communities of color. If that argument were true, then the horizon for community rights wouldn’t be particularly bright. An inability to win over and unite the working class – the ordinary masses who are the majority of people – guarantees more of the same. It means that the ruling class minority won’t face a credible challenge to their disproportionate power and influence in society.

While this sort of rigidity and inertia in the existing, unequal political-economic system is unfortunately the rule rather than the exception, Walton’s electoral performance gives hope that the shields around the status quo might soon be pierced in Buffalo. Directly contradicting the common narrative about leftist candidates’ limited appeal, data suggest that Walton’s base was made up of unpropertied voters, voters of color, and voters living in the city’s lowest wealth communities.

My own statistical estimates show that Walton won the renter vote by nearly a 2-1 margin. She also appears to have won a majority of ballots cast by Black voters; and, while there’s too much uncertainty to say that Walton definitively won among Latinx voters and other voters of color, the evidence points in that direction.

Simply put, between the primary and general elections, Walton ostensibly evolved her base into a geographically and racially diverse coalition of working-class voters tired of the status quo. That’s precisely the type of base that, if properly reinforced and activated, can acquire and wield the level of people power sufficient to build a new system that values and protects community rights. Moving in that direction means tapping into the energy and momentum that Walton helped to harness. Drawing on CELDF’s lessons for people’s movements, it means formulating a long-term theory of change, crafting strategies, choosing tactics, and bringing the envisioned change to life through direct action.

The posting of this piece is a reflection of CELDF’s commitment to featuring diverse perspectives and ideas in the quest to bring about a community rights and rights of nature existence into full being.

Russell Weaver is a geographer and Director of Research at the Cornell University ILR Buffalo Co-Lab, where he studies collective action and economic democracy. The views expressed in this post are his and do not reflect the opinions of his employer.

Twitter: @RustBeltGeo