Written by Taru Taylor

Authors Note: I addressed this speech on police reform to a group of high-school students set to graduate this year. I meant to impress upon them the fact that We the People, ultimately, define the rule of law. For our informed consent is what legitimizes government. And so it’s up to us to command all of our public servants, including cops. Thanks to the Twenty-sixth Amendment, the awesome responsibilities of citizenship are now thrust upon newly-minted citizens who turn 18 this year. We the People must nullify the despotic doctrine so-called qualified immunity. The buck stops with every single citizen from their eighteenth birthday.

Introducing the Rule of Law

Since most of you are 18 years old, or turning 18 very soon, I want to welcome you to the First Branch of Government. For there are four branches of government, not three. The citizenry, the legislature, the executive branch, and the judiciary.

We learn all about “checks and balances” in civics, but we tend to learn it in terms of the other three branches of government. For example, how the president can veto congress and congress can, in turn, override his veto; how the Supreme Court can nullify federal legislation or executive orders, and so on.

But We the People check and balance too. As electors we check and balance elected officials by voting for them when we like them and by voting them out of office when we don’t.

As jurors we check and balance judges with our more common-sense notions of justice. In fact, in Federalist no. 83, Alexander Hamilton argues that trial by jury is a valuable check against judicial despotism. He says: “The strongest argument in [the jury’s] favor is, that it is a security against [judicial] corruption.”

We the People are the First Branch of Government. Ultimately, We define the Rule of Law. We must ever remind our public servants that The Constitution is, after all, an employee handbook.

The Preamble is a statement of purpose from us, the collective boss. Articles 1-3 spell out the duties and limitations of our federal employees. Article 4 focuses on our state-level employees. The Bill of Rights protects us employers from employees who may step out of their place of public servitude.

Article 1 Section 1 vests legislative powers in Congress. Article 2 Section 1 vests executive power in the President. Article 3 Section 1 vests judicial power, ultimately, in the Supreme Court. But the Tenth Amendment reserves all powers not delegated to the other three branches of government to the states, or to the People. The Tenth Amendment literally mandates power to the People.

Nor is the citizenry, the collective boss, limited to propertied white men.

The Fifteenth Amendment made Black men the boss too. Women got the right to be the boss thanks to the Nineteenth Amendment. The Twenty-sixth Amendment gave U.S.-born citizens the right to be the boss on their eighteenth birthdays. And so I say to you, newly-minted bosses, congratulations.

In short, We the People make the Rule of Law.

Alexander Hamilton, concluding Federalist no. 85, argued that The Constitution must be established by the voluntary consent of the whole people. Writing in the 1780s, he did more or less limit “the people” to propertied white men like him. But as I write in 2021, we have had millions of Black voters, a Black president, and we now have a Black female vice president.

Back to 1776. The Declaration of Independence framed our social contract in terms of equality and the inalienable rights of life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness. “That to secure these Rights, Governments are instituted among Men, deriving their just Powers from the Consent of the Governed.”

Thus Hamilton and Thomas Jefferson based the social contract on the consent of the people. They understood the Rule of Law in terms of the informed consent of the citizenry.

Yet John Adams probably best expressed the Rule of Law when he said: “Ours is a government of laws and not of men.”

So when We determine the constitutionality of the 18,000 police departments in our 50 states plus D.C., we must ever do so in terms of the Rule of Law.

Police officers are known as “law enforcement.” For their professional purpose is to enforce the law. Moreover, The Constitution, according to Article 6, is “the supreme Law of the Land.”

Let’s spell out this syllogism:

Police officers are supposed to enforce the law.

The Constitution is “the supreme Law of the Land.”

Therefore, police officers are supposed to enforce The Constitution.

I never heard of any police officer swearing an oath to their union contract. Nor do they swear an oath to any of the 50 different state constitutions plus D.C. But every police officer does swear an oath to uphold and defend The Constitution.

The point is, whenever We allow police officers to frame the issue of proper and professional policing, in local terms, We play whack-a-mole with 18,000 different police departments. Or, if you like, We face a Hydra, the mythological beast that grew two new heads every time Hercules chopped off one of its heads.

Which is why We must frame the issue of proper policing in terms of the Rule of Law, that is, in terms of “the supreme Law of the Land,” The Constitution. If police officers are really “law enforcement,” they must enforce The Constitution. As street-level strict constructionists of The Constitution.

Their job is to apprehend the criminal suspect with minimal violence and then take them before the magistrate, all the while respecting the suspect’s presumed innocence. Properly understood, they are gofers for the judge. Insofar as they go beyond their proper job description and fail to execute The Constitution in strict terms, they are lawless law enforcement.

I’m now going to share with you a very useful heuristic that will enable you to tell, in just about any situation involving a person and a public official, whether the Rule of Law, or lawlessness, applies.

And then I’m going to apply this heuristic to the doctrine of qualified immunity, which the Supreme Court made law in the case of Pierson v. Ray in 1967. I’m going to argue that Justice William Douglas’ lone dissent in that case provides our template for police reform going forward. His dissent should frame our efforts to nullify the despotic doctrine so-called “qualified immunity.”

The Hohfeld Rule

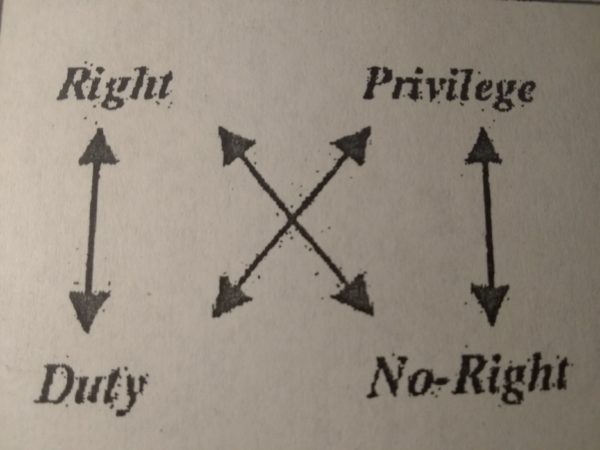

Wesley Hohfeld, an American legal scholar who came to prominence during the early twentieth century, posited four basic legal relations. But today we’re going to focus on the two legal relations that pertain to republican government: the right—duty relation on the left of the diagram, and the privilege—no-right relation on the right.

Every time a person confronts a public official, one of the two relations applies. The person has either a right or they have a no-right. The public official has either a duty or they have a privilege.

Hence, the Hohfeld Rule and its diagram.

Here’s a simple way to think about these legal terms:

A duty is what I must do. A privilege is what I may do. A right is what some other person must do for me.

Bear in mind that Hohfeld was of the legal realist school of jurisprudence. To him, whether or not a person has a right depends on whether the court would mandate performance of its correlative duty. In other words, the ultimate test of duty is whether the court would find for the plaintiff in a lawsuit. Hohfeld dispensed with abstract notions of right. He thought that courts determine the meaning of rights and duties.

The heuristic, the Hohfeld Rule, is as follows:

Always look for the duty before you use the term right.

The pertinent questions are:

1) Who is the duty-bearer?

2) Does their expected conduct correspond with what you call a right?

If not, then no-right.

If I can act, and be safe from the courts, then I have a privilege.

Now let’s work out the implications of the Hohfeld Rule regarding the doctrine of qualified immunity.

The Hohfeld Rule Regarding Pierson v. Ray

Pierson v. Ray is the 1967 case in which the Supreme Court made qualified immunity the law of the land. The case involved a group of white and Black clergymen who had attempted to use segregated facilities in a bus terminal in Jackson, Mississippi. A municipal court convicted them of violating a state statute that made it a crime to congregate in a public place if they might breach the peace and then refuse to disperse when so ordered by a police officer. They were acquitted on appeal.

The clergymen then sued the municipal-court judge and the police officers who arrested them under Section 1 of the Ku Klux Klan Act of 1871, which makes liable “every person” who under color of law intentionally and knowingly deprives another person of their rights under The Constitution.

The Court held that the Act had in no way impaired the common law’s absolute immunity for judges in their judicial acts. It held that the police officers had a qualified immunity which would protect them from liability if the court found, on retrial, that the officers acted in the good faith belief that the statute they were enforcing was constitutional.

If we look at the diagram of the Hohfeld Rule, we can see that the Pierson ruling gave judges and police officers a privilege. It thus gave citizens a no-right. The decision brings to mind the legal axiom that where there is no remedy, there is no right.

But James Madison had argued in Federalist no. 43 that if the federal government would guarantee every state a republican form of government, “the superintending government ought clearly to possess authority to defend the system against aristocratic or monarchical innovations.” Indeed, Section 5 of the Fourteenth Amendment declared that Congress has this very same authority, with the “power to enforce, by appropriate legislation, the provisions of this article.” This means that the Civil Rights Acts were well within congressional mandate.

The Court decided wrong when it nullified the Ku Klux Klan Act. For, to use the language of Madison, the Pierson ruling sanctioned an “aristocratic innovation” that subverts our republican form of government.

But what is a republic?

In Federalist no. 39, Madison defined republic as “government which derives all its powers directly or indirectly from the great body of the people, and is administered by persons holding their offices during pleasure, for a limited period, or during good behavior.”

Based on Madison’s definition, we can safely say that a republic is a society on the left side of the Hohfeld diagram. It is a society where every citizen is on the top left right section and every public official is on the bottom left duty section.

So far as we know, the republic is the only form of government that can bring about equality in a nation of millions. It’s thus on the left side of the diagram. But the different types of unequal societies on the right side of the diagram are legion. They include aristocracy, monarchy, apartheid society, and the police state. In unequal societies, some persons are on the diagram’s bottom right no-right section and select persons are on its top right privilege section.

As Justice Douglas makes clear in his dissent, the Pierson majority aggravated our separate and unequal society. Through the Ku Klux Klan Act, Congress had meant to put all state actors, including judges and police officers, on the Hohfeld diagram’s bottom left duty section. Which would have put all citizens, including Black people, on its top left right section. But Pierson, to this day, echoes the infamous Dred Scott decision of 1857: “the negro has no rights which white men are bound to respect.”

Douglas Dissenting in Pierson v Ray

The Rule of Law diametrically opposes divine right. The American revolutionaries of the 1770s and 1780s stood for republican principle against the divine right of kings in the person of George III. They ended up creating a slave-lord republic that endured until the Civil War. Even so, the documents that define our social contract, especially The Declaration of Independence and The Constitution, do point the way toward the Rule of Law.

Regarding this present topic of constitutional policing, Douglas’ Pierson dissent epitomizes the Rule of Law.

The Ku Klux Klan Act says that “every person” who under color of state law or custom “subjects, or causes to be subjected, any citizen … to the deprivation of any rights, privileges, or immunities secured by the Constitution and laws, shall be liable to the party injured in an action at law, suit in equity, or other proper proceeding for redress.” Douglas makes clear that when the Act says “every person,” it means every person. Not every person except judges or police officers.

Douglas notes the “lawlessness” that pervaded the South after the Civil War and thus necessitated the Civil Rights Acts. And lawlessness was not limited to the South nor to the namesake of the Act in question, the Ku Klux Klan. Douglas describes some judges as “instruments of oppression.” Furthermore, he describes some state courts as “instruments of suppression of civil rights.” Writing in 1967, he makes plain the continuing relevance of the Civil Rights Acts enacted during the Reconstruction era: “The methods may have changed; the means may have become more subtle; but the wrong to be remedied still exists.”

As for the argument that judges and police officers need immunity from liability to be independent and to do their jobs effectively, this is what he had to say about that: “The argument that the actions of public officials must not be subjected to public scrutiny because to do so would have an inhibiting effect on their work, is but a more sophisticated way of saying, “The King can do no wrong.”

In other words, qualified immunity is but an updated version of the divine right of kings. Or, if we look at the Hohfeld diagram, privilege denotes the divine right of judges and police officers. And no-right denotes, more often than not, Dred Scott as applied to Black and brown people.

Justice William Douglas did champion the Rule of Law. But he was in lone dissent.

Conclusion

Fifty-four years later, apologists for lawless law enforcement and police brutality are still saying, in so many words, that “The King can do no wrong.” Thanks to the persistence of qualified immunity, the “king” either sits on a bench or they wear a blue uniform.

But We are citizens, all four branches of government. Our democratic republic brooks no kings nor queens, no princes nor princesses. We are citizens all. Of a republic, not a police state.

We the People must therefore overturn Pierson. We must insist that our public servants, our tax-paid employees, even those who wear black robes or blue uniforms, guarantee our republican form of government as mandated by Article 4 Section 4 of The Constitution.

The posting of this piece is a reflection of CELDF’s commitment to featuring diverse perspectives and ideas in the quest to bring about a community rights and rights of nature existence into full being.

Photo by Joshua Sukoff on Unsplash