By Simon-Davis Cohen and Lindsey Schromen-Wawrin

Biden’s January 27, 2021 executive order “Tackling the Climate Crisis at Home and Abroad” reveals the way corporate power is protected from democracy.

“We face a climate crisis that threatens our people and communities, public health and economy, and, starkly, our ability to live on planet Earth,” the order reads. However, rather than seek to govern the private fossil fuel sector, the order narrowly confines itself to future oil and gas leases on public lands. That’s because current interpretations of the U.S. Constitution ties the hands of the government from substantively governing existing fossil fuel infrastructure.

This tells us something about that “applicable law,” namely, the U.S. Constitution and the U.S. Supreme Court’s interpretation and manipulation of law to insulate corporate power.

Along with committing to a “procurement strategy” to convert its own fleets to electric vehicles, infusing climate into its foreign relations, considering the adjustment of royalties and subsidies, the order says the executive branch will, “to the extent consistent with applicable law…pause new oil and natural gas leases on public lands or in offshore waters.”

The keywords are “new” and “public lands.” Biden does not seek to govern private property and existing leases on public lands are not impacted.

A municipal analogy can be seen in cities. Cleveland is limited by state law from raising the minimum wage for all workers. So, as a concession, Cleveland merely raised the wage of its own employees. Doing nothing for private sector workers.

Because Biden’s order remains “consistent with applicable law,” it does nothing to govern private oil and gas leasing, or existing leases on federal lands. This tells us something about that “applicable law,” namely, the U.S. Constitution and the U.S. Supreme Court’s interpretation and manipulation of law to insulate corporate power.

Biden’s order operates within the confines of a system of law that has elevated fossil fuel companies into “persons” that enjoy property rights including under the Due Process Clause. (A corruption of the 14th Amendment that was actually meant to create some justice for formerly enslaved people.)

Of course, it’s not up to Biden to change this status quo. But the reasons Biden’s order is so weak exposes a structure that will seek to limit bolder future action to address the climate crisis.

Along with making changes to diplomatic relations, commitments, and calls to address the climate crisis, the order articulates a vision for federal spending “to spur innovation, commercialization, and deployment of clean energy technologies and infrastructure.”

Focusing mainly on spending allows it to avoid mandating changes within the private sector. It only calls for strategies to encourage things like “broad participation in the goal of conserving 30 percent of our lands and waters by 2030.”

The order does what it can within existing law. It’s up to movements to change that law. That means expanding constitutional demands beyond procedural demands to abolish the Electoral College and reform the courts, and into substantively addressing corporate constitutional privileges enshrined in the Constitution.

This piece was originally published here in Common Dreams.

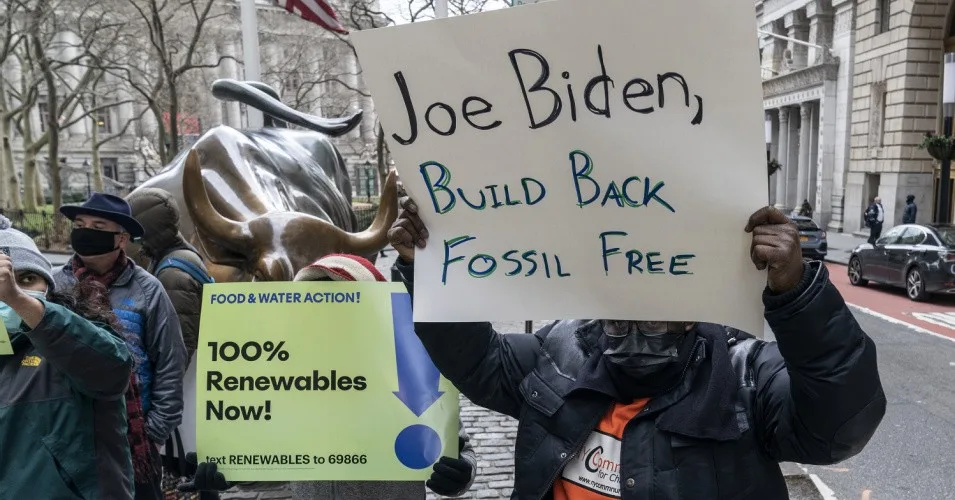

Photo: Lev Radin/Pacific Press/LightRocket via Getty Images