Written by Ron Whyte

Editor’s Note: Where waste goes and exists is not a coincidence. This compelling guest blog from Ron Whyte, with Mural Arts Philadelphia, shows how civic participation, public education and systemic thinking can be used together to build power, improve lives and challenge structures that rely on dispossession and oppression, in South Philadelphia.

During its period of post-industrial decline from the mid 1970’s to the early 1990’s, Philadelphia earned the unfortunate nickname of ‘Filthadelphia,’ having become infamous for the trash, litter and dumping that blighted its streets. Yet if we look back in time we will observe that up until the 1950’s Philadelphia was consistently ranked as one of the cleanest cities in the country. In fact, Benjamin Franklin organized the very first street sweeping program during the colonial era, right here in Philadelphia in the 1750’s. In 1917, Philadelphia was one of the first U.S. cities to deploy modern street sweeping technology. So, what changed between the 1950’s and the mid-late 1970’s? The answer to this question reveals a layer of complexity that is almost never associated with the seemingly simple and straightforward issue of trash.

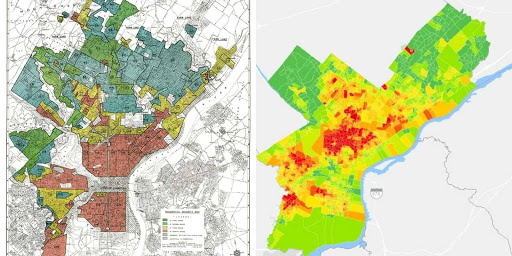

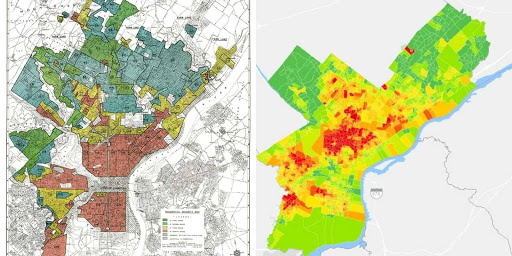

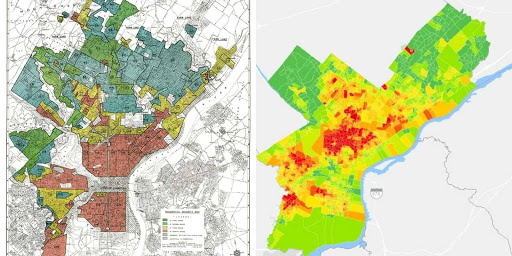

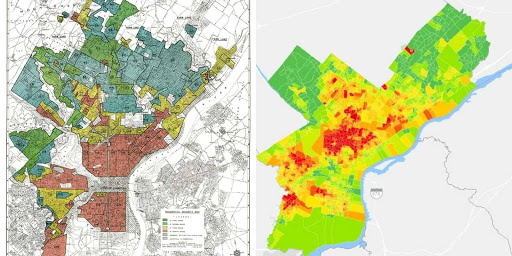

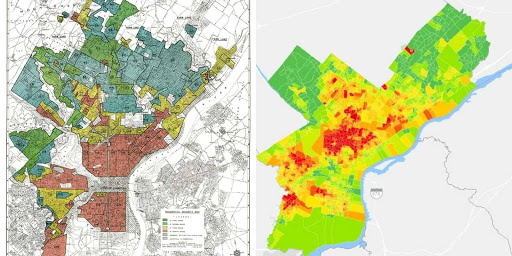

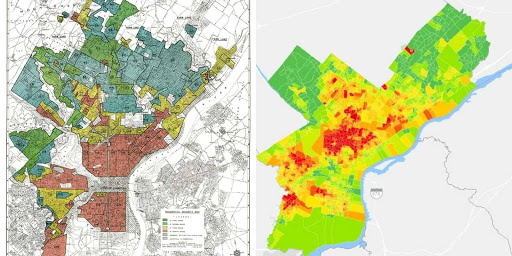

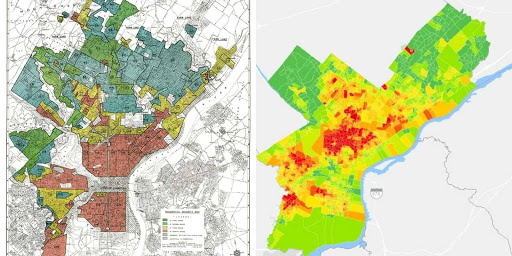

Left, 1937 Philadelphia redlining map; Right, 2018 Philadelphia Litter Index

By the 1950’s, Philadelphia was undergoing the same demographic shifts as other major cities. These changes were driven by one of the largest internal migrations in world history — The Great Migration. Between 1910 and 1970, around six million Black people packed up and fled the poverty, oppression, segregation and racial terror of the Jim Crow South. These internally displaced persons, or refugees, ran into the arms of a less overtly violent, but no less insidious form of systemic racism here in the North. The chronic trash, blight and social dysfunction that plagues low income communities of color in our major cities is a reflection of the systematic disenfranchisement and environmental racism these communities have been subjected to

Trash Academy (a program of Mural Arts Philadelphia’s Environmental Justice Institute) will not approach the issue of trash and litter in urban neighborhoods without putting the situation in its proper historical and socio-political context.

Our recent education and awareness campaign on the benefits of reusable bags is an example of our praxis in action. Single use plastic bags are being banned in cities across the country and around the world, and when we were invited to join a coalition of environmental non-profits and community groups taking action on this issue here in Philadelphia, we welcomed the opportunity. Our unique blend of art, activism and community advocacy was an integral part of the process that led to legislation to ban plastic bags here in Philadelphia. Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, implementation of the ban was delayed until 2021. The state legislature has also passed legislation to interfere in the city’s power to enact the ban Nevertheless, for the young people in our cohort especially, this win was a validation of sorts and yet more proof that art has a crucial role to play in social movements.

We complicate the issue of trash. We recognize that we cannot address the trash issue without acknowledging pre-existing systems of exploitation and oppression. We recognize that mitigation strategies must flow organically from those who have the lived experience of struggling day to day with the problem we’re attempting to solve. We engage community members in participant-led research, education, advocacy, and civic engagement while creating and testing innovative, grassroots solutions to the issue of trash through a horizontal collaborative process. We also encourage youth leadership, positioning young people to take the lead in educating and transforming their own communities. And, because we’re embedded within Mural Arts, the largest public arts organization in the country, we’re committed to approaching the trash issue through the doorway of art and creativity, utilizing game play, fun and discovery as tools and as springboards for more in depth analysis and conversations.When we see disposable coffee cups clogging up a storm drain, or plastic bags fluttering from tree limbs, our first thought is usually something along the lines of, “ugh, people are so disgusting!” And I must admit that when I first became involved with Trash Academy in 2016 I was someone who viewed the problem of trash, litter and dumping to be primarily one of personal consumption and personal habits. The misconception that we would have cleaner streets if only litter bugs would simply learn to hold onto their trash until they reached a trash can, or if people would just stop throwing trash out of their car windows. In the era of neoliberalism, blaming individuals for systemic social problems is definitely the trend du jour.

When we see disposable coffee cups clogging up a storm drain, or plastic bags fluttering from tree limbs, our first thought is usually something along the lines of, “ugh, people are so disgusting!” And I must admit that when I first became involved with Trash Academy in 2016 I was someone who viewed the problem of trash, litter and dumping to be primarily one of personal consumption and personal habits. The misconception that we would have cleaner streets if only litter bugs would simply learn to hold onto their trash until they reached a trash can, or if people would just stop throwing trash out of their car windows. In the era of neoliberalism, blaming individuals for systemic social problems is definitely the trend du jour.

However, the complication that arises when we attempt to totally shift the blame onto corporations and systems is that residents who desperately want to see the trash go away are constantly noticing the bad habits and behaviors of their neighbors. We have perceived this dynamic through our work in South Philadelphia, where the trash crisis is particularly pronounced. The “in your face” bad behavior (littering, short dumping, neglecting to clean the front of one’s property) helps obscure the larger systemic issues and contributes to finger pointing and horizontal hostility. This dynamic highlights why the trash issue is so particularly thorny; yes, larger systemic issues are driving all of this dysfunction, and yet, individual decisions and our participation in consumer culture are factors that cannot be ignored either.

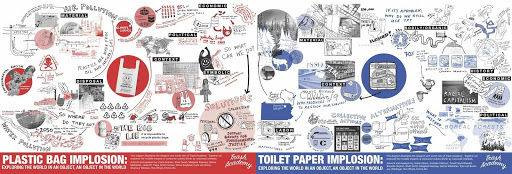

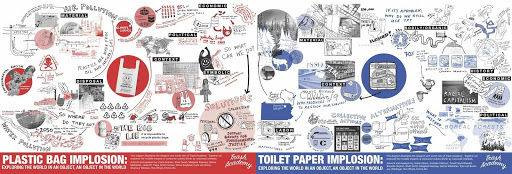

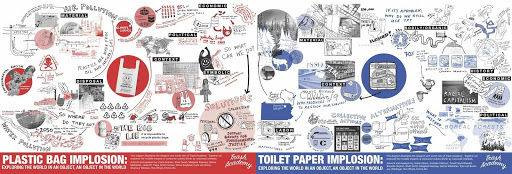

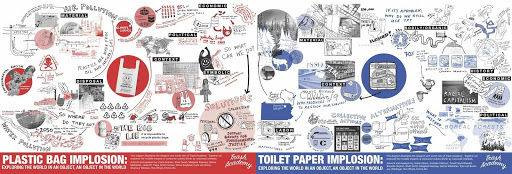

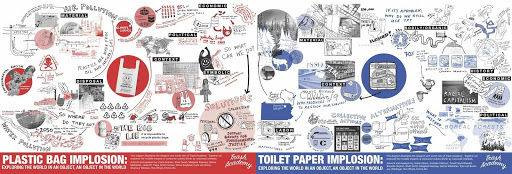

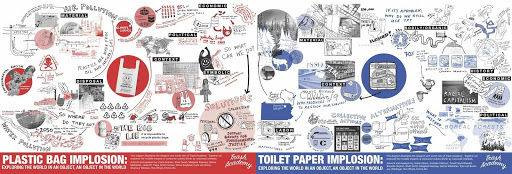

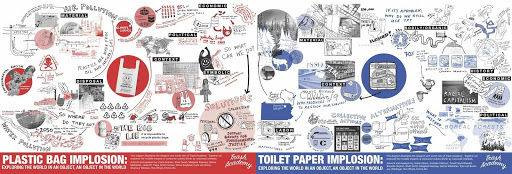

Educational tools are a key part of how we educate and raise awareness, and we have developed one to specifically address this dichotomy of personal behavior/consumption versus corporate and systemic impacts. We were inspired by the implosion research method pioneered by professor Donna Haraway and introduced to us by design strategist Gamar Markarian. The implosion is a very effective tool for unpacking the hidden complexities embedded within seemingly simple objects. The implosion method sees how every issue, object or reaction is “unpackable.”

Our innovation on the implosion method was to visualize it (with help from lead artist Margaret Kearney). We created a space for collaboration between artists, community members, and activists. Our implosions function as stand-alone educational tools, or, they can be complimented by webinars we have developed in collaboration with community members and youth in our cohort. Our ‘implosion’ project was in large part inspired by events taking place during the initial COVID-19 lockdown, particularly the panic buying of toilet paper. While some have viewed the pandemic as a reason to jettison thoughts of sustainability, we are highlighting the fact that the interwoven crises of climate change, environmental degradation and environmental racism require us to be even more committed to protecting what remains while curbing the destructive impacts of consumer culture.

‘places to which the dispossessed have been banished’

Once the trash issue has been complicated we notice that the places associated with cleanliness are usually populated by certain types of people, while the places associated with grime and disorder are primarily the places to which the dispossessed have been banished. And yet, the places associated with cleanliness are the places from which the majority of the trash is being generated.

Call it capitalism’s detritus, and it’s a global crisis.

Those with privilege have the luxury of not having to interact with the waste they create — it’s ferried away with twice weekly trash pick ups and regular street sweeping and cleaning, or, it’s sent overseas to become a problem for the developing world. It’s no coincidence that polluting fossil fuel projects have inflicted South Philadelphia for generations. And you’ll almost never see trash littering the well manicured lawns and green spaces of the suburbs, but not because the people who live there are cleaner or more conscientious than urban, inner city dwellers. Communities that have not been targeted by the police and flooded with drugs and guns are in a much better position to exercise the kind of community care and solidarity that fosters a sense of belonging and collective ownership over one’s neighborhood. And, of course, these “clean” communities are flush with resources and political power.

Ron Whyte is an environmental activist based in Philadelphia. Photo by Teishka Smith.

Ron Whyte is an environmental activist based in Philadelphia. Photo by Teishka Smith.

Written by Ron Whyte

Editor’s Note: Where waste goes and exists is not a coincidence. This compelling guest blog from Ron Whyte, with Mural Arts Philadelphia, shows how civic participation, public education and systemic thinking can be used together to build power, improve lives and challenge structures that rely on dispossession and oppression, in South Philadelphia.

During its period of post-industrial decline from the mid 1970’s to the early 1990’s, Philadelphia earned the unfortunate nickname of ‘Filthadelphia,’ having become infamous for the trash, litter and dumping that blighted its streets. Yet if we look back in time we will observe that up until the 1950’s Philadelphia was consistently ranked as one of the cleanest cities in the country. In fact, Benjamin Franklin organized the very first street sweeping program during the colonial era, right here in Philadelphia in the 1750’s. In 1917, Philadelphia was one of the first U.S. cities to deploy modern street sweeping technology. So, what changed between the 1950’s and the mid-late 1970’s? The answer to this question reveals a layer of complexity that is almost never associated with the seemingly simple and straightforward issue of trash.

Left, 1937 Philadelphia redlining map; Right, 2018 Philadelphia Litter Index

By the 1950’s, Philadelphia was undergoing the same demographic shifts as other major cities. These changes were driven by one of the largest internal migrations in world history — The Great Migration. Between 1910 and 1970, around six million Black people packed up and fled the poverty, oppression, segregation and racial terror of the Jim Crow South. These internally displaced persons, or refugees, ran into the arms of a less overtly violent, but no less insidious form of systemic racism here in the North. The chronic trash, blight and social dysfunction that plagues low income communities of color in our major cities is a reflection of the systematic disenfranchisement and environmental racism these communities have been subjected to

Trash Academy (a program of Mural Arts Philadelphia’s Environmental Justice Institute) will not approach the issue of trash and litter in urban neighborhoods without putting the situation in its proper historical and socio-political context.

Our recent education and awareness campaign on the benefits of reusable bags is an example of our praxis in action. Single use plastic bags are being banned in cities across the country and around the world, and when we were invited to join a coalition of environmental non-profits and community groups taking action on this issue here in Philadelphia, we welcomed the opportunity. Our unique blend of art, activism and community advocacy was an integral part of the process that led to legislation to ban plastic bags here in Philadelphia. Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, implementation of the ban was delayed until 2021. The state legislature has also passed legislation to interfere in the city’s power to enact the ban Nevertheless, for the young people in our cohort especially, this win was a validation of sorts and yet more proof that art has a crucial role to play in social movements.

We complicate the issue of trash. We recognize that we cannot address the trash issue without acknowledging pre-existing systems of exploitation and oppression. We recognize that mitigation strategies must flow organically from those who have the lived experience of struggling day to day with the problem we’re attempting to solve. We engage community members in participant-led research, education, advocacy, and civic engagement while creating and testing innovative, grassroots solutions to the issue of trash through a horizontal collaborative process. We also encourage youth leadership, positioning young people to take the lead in educating and transforming their own communities. And, because we’re embedded within Mural Arts, the largest public arts organization in the country, we’re committed to approaching the trash issue through the doorway of art and creativity, utilizing game play, fun and discovery as tools and as springboards for more in depth analysis and conversations.When we see disposable coffee cups clogging up a storm drain, or plastic bags fluttering from tree limbs, our first thought is usually something along the lines of, “ugh, people are so disgusting!” And I must admit that when I first became involved with Trash Academy in 2016 I was someone who viewed the problem of trash, litter and dumping to be primarily one of personal consumption and personal habits. The misconception that we would have cleaner streets if only litter bugs would simply learn to hold onto their trash until they reached a trash can, or if people would just stop throwing trash out of their car windows. In the era of neoliberalism, blaming individuals for systemic social problems is definitely the trend du jour.

When we see disposable coffee cups clogging up a storm drain, or plastic bags fluttering from tree limbs, our first thought is usually something along the lines of, “ugh, people are so disgusting!” And I must admit that when I first became involved with Trash Academy in 2016 I was someone who viewed the problem of trash, litter and dumping to be primarily one of personal consumption and personal habits. The misconception that we would have cleaner streets if only litter bugs would simply learn to hold onto their trash until they reached a trash can, or if people would just stop throwing trash out of their car windows. In the era of neoliberalism, blaming individuals for systemic social problems is definitely the trend du jour.

However, the complication that arises when we attempt to totally shift the blame onto corporations and systems is that residents who desperately want to see the trash go away are constantly noticing the bad habits and behaviors of their neighbors. We have perceived this dynamic through our work in South Philadelphia, where the trash crisis is particularly pronounced. The “in your face” bad behavior (littering, short dumping, neglecting to clean the front of one’s property) helps obscure the larger systemic issues and contributes to finger pointing and horizontal hostility. This dynamic highlights why the trash issue is so particularly thorny; yes, larger systemic issues are driving all of this dysfunction, and yet, individual decisions and our participation in consumer culture are factors that cannot be ignored either.

Educational tools are a key part of how we educate and raise awareness, and we have developed one to specifically address this dichotomy of personal behavior/consumption versus corporate and systemic impacts. We were inspired by the implosion research method pioneered by professor Donna Haraway and introduced to us by design strategist Gamar Markarian. The implosion is a very effective tool for unpacking the hidden complexities embedded within seemingly simple objects. The implosion method sees how every issue, object or reaction is “unpackable.”

Our innovation on the implosion method was to visualize it (with help from lead artist Margaret Kearney). We created a space for collaboration between artists, community members, and activists. Our implosions function as stand-alone educational tools, or, they can be complimented by webinars we have developed in collaboration with community members and youth in our cohort. Our ‘implosion’ project was in large part inspired by events taking place during the initial COVID-19 lockdown, particularly the panic buying of toilet paper. While some have viewed the pandemic as a reason to jettison thoughts of sustainability, we are highlighting the fact that the interwoven crises of climate change, environmental degradation and environmental racism require us to be even more committed to protecting what remains while curbing the destructive impacts of consumer culture.

‘places to which the dispossessed have been banished’

Once the trash issue has been complicated we notice that the places associated with cleanliness are usually populated by certain types of people, while the places associated with grime and disorder are primarily the places to which the dispossessed have been banished. And yet, the places associated with cleanliness are the places from which the majority of the trash is being generated.

Call it capitalism’s detritus, and it’s a global crisis.

Those with privilege have the luxury of not having to interact with the waste they create — it’s ferried away with twice weekly trash pick ups and regular street sweeping and cleaning, or, it’s sent overseas to become a problem for the developing world. It’s no coincidence that polluting fossil fuel projects have inflicted South Philadelphia for generations. And you’ll almost never see trash littering the well manicured lawns and green spaces of the suburbs, but not because the people who live there are cleaner or more conscientious than urban, inner city dwellers. Communities that have not been targeted by the police and flooded with drugs and guns are in a much better position to exercise the kind of community care and solidarity that fosters a sense of belonging and collective ownership over one’s neighborhood. And, of course, these “clean” communities are flush with resources and political power.

Ron Whyte is an environmental activist based in Philadelphia. Photo by Teishka Smith.

Ron Whyte is an environmental activist based in Philadelphia. Photo by Teishka Smith.

Written by Ron Whyte

Editor’s Note: Where waste goes and exists is not a coincidence. This compelling guest blog from Ron Whyte, with Mural Arts Philadelphia, shows how civic participation, public education and systemic thinking can be used together to build power, improve lives and challenge structures that rely on dispossession and oppression, in South Philadelphia.

During its period of post-industrial decline from the mid 1970’s to the early 1990’s, Philadelphia earned the unfortunate nickname of ‘Filthadelphia,’ having become infamous for the trash, litter and dumping that blighted its streets. Yet if we look back in time we will observe that up until the 1950’s Philadelphia was consistently ranked as one of the cleanest cities in the country. In fact, Benjamin Franklin organized the very first street sweeping program during the colonial era, right here in Philadelphia in the 1750’s. In 1917, Philadelphia was one of the first U.S. cities to deploy modern street sweeping technology. So, what changed between the 1950’s and the mid-late 1970’s? The answer to this question reveals a layer of complexity that is almost never associated with the seemingly simple and straightforward issue of trash.

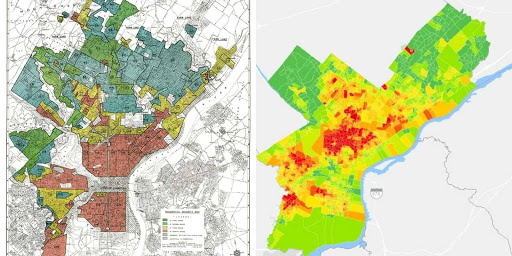

Left, 1937 Philadelphia redlining map; Right, 2018 Philadelphia Litter Index

By the 1950’s, Philadelphia was undergoing the same demographic shifts as other major cities. These changes were driven by one of the largest internal migrations in world history — The Great Migration. Between 1910 and 1970, around six million Black people packed up and fled the poverty, oppression, segregation and racial terror of the Jim Crow South. These internally displaced persons, or refugees, ran into the arms of a less overtly violent, but no less insidious form of systemic racism here in the North. The chronic trash, blight and social dysfunction that plagues low income communities of color in our major cities is a reflection of the systematic disenfranchisement and environmental racism these communities have been subjected to

Trash Academy (a program of Mural Arts Philadelphia’s Environmental Justice Institute) will not approach the issue of trash and litter in urban neighborhoods without putting the situation in its proper historical and socio-political context.

Our recent education and awareness campaign on the benefits of reusable bags is an example of our praxis in action. Single use plastic bags are being banned in cities across the country and around the world, and when we were invited to join a coalition of environmental non-profits and community groups taking action on this issue here in Philadelphia, we welcomed the opportunity. Our unique blend of art, activism and community advocacy was an integral part of the process that led to legislation to ban plastic bags here in Philadelphia. Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, implementation of the ban was delayed until 2021. The state legislature has also passed legislation to interfere in the city’s power to enact the ban Nevertheless, for the young people in our cohort especially, this win was a validation of sorts and yet more proof that art has a crucial role to play in social movements.

We complicate the issue of trash. We recognize that we cannot address the trash issue without acknowledging pre-existing systems of exploitation and oppression. We recognize that mitigation strategies must flow organically from those who have the lived experience of struggling day to day with the problem we’re attempting to solve. We engage community members in participant-led research, education, advocacy, and civic engagement while creating and testing innovative, grassroots solutions to the issue of trash through a horizontal collaborative process. We also encourage youth leadership, positioning young people to take the lead in educating and transforming their own communities. And, because we’re embedded within Mural Arts, the largest public arts organization in the country, we’re committed to approaching the trash issue through the doorway of art and creativity, utilizing game play, fun and discovery as tools and as springboards for more in depth analysis and conversations.When we see disposable coffee cups clogging up a storm drain, or plastic bags fluttering from tree limbs, our first thought is usually something along the lines of, “ugh, people are so disgusting!” And I must admit that when I first became involved with Trash Academy in 2016 I was someone who viewed the problem of trash, litter and dumping to be primarily one of personal consumption and personal habits. The misconception that we would have cleaner streets if only litter bugs would simply learn to hold onto their trash until they reached a trash can, or if people would just stop throwing trash out of their car windows. In the era of neoliberalism, blaming individuals for systemic social problems is definitely the trend du jour.

When we see disposable coffee cups clogging up a storm drain, or plastic bags fluttering from tree limbs, our first thought is usually something along the lines of, “ugh, people are so disgusting!” And I must admit that when I first became involved with Trash Academy in 2016 I was someone who viewed the problem of trash, litter and dumping to be primarily one of personal consumption and personal habits. The misconception that we would have cleaner streets if only litter bugs would simply learn to hold onto their trash until they reached a trash can, or if people would just stop throwing trash out of their car windows. In the era of neoliberalism, blaming individuals for systemic social problems is definitely the trend du jour.

However, the complication that arises when we attempt to totally shift the blame onto corporations and systems is that residents who desperately want to see the trash go away are constantly noticing the bad habits and behaviors of their neighbors. We have perceived this dynamic through our work in South Philadelphia, where the trash crisis is particularly pronounced. The “in your face” bad behavior (littering, short dumping, neglecting to clean the front of one’s property) helps obscure the larger systemic issues and contributes to finger pointing and horizontal hostility. This dynamic highlights why the trash issue is so particularly thorny; yes, larger systemic issues are driving all of this dysfunction, and yet, individual decisions and our participation in consumer culture are factors that cannot be ignored either.

Educational tools are a key part of how we educate and raise awareness, and we have developed one to specifically address this dichotomy of personal behavior/consumption versus corporate and systemic impacts. We were inspired by the implosion research method pioneered by professor Donna Haraway and introduced to us by design strategist Gamar Markarian. The implosion is a very effective tool for unpacking the hidden complexities embedded within seemingly simple objects. The implosion method sees how every issue, object or reaction is “unpackable.”

Our innovation on the implosion method was to visualize it (with help from lead artist Margaret Kearney). We created a space for collaboration between artists, community members, and activists. Our implosions function as stand-alone educational tools, or, they can be complimented by webinars we have developed in collaboration with community members and youth in our cohort. Our ‘implosion’ project was in large part inspired by events taking place during the initial COVID-19 lockdown, particularly the panic buying of toilet paper. While some have viewed the pandemic as a reason to jettison thoughts of sustainability, we are highlighting the fact that the interwoven crises of climate change, environmental degradation and environmental racism require us to be even more committed to protecting what remains while curbing the destructive impacts of consumer culture.

‘places to which the dispossessed have been banished’

Once the trash issue has been complicated we notice that the places associated with cleanliness are usually populated by certain types of people, while the places associated with grime and disorder are primarily the places to which the dispossessed have been banished. And yet, the places associated with cleanliness are the places from which the majority of the trash is being generated.

Call it capitalism’s detritus, and it’s a global crisis.

Those with privilege have the luxury of not having to interact with the waste they create — it’s ferried away with twice weekly trash pick ups and regular street sweeping and cleaning, or, it’s sent overseas to become a problem for the developing world. It’s no coincidence that polluting fossil fuel projects have inflicted South Philadelphia for generations. And you’ll almost never see trash littering the well manicured lawns and green spaces of the suburbs, but not because the people who live there are cleaner or more conscientious than urban, inner city dwellers. Communities that have not been targeted by the police and flooded with drugs and guns are in a much better position to exercise the kind of community care and solidarity that fosters a sense of belonging and collective ownership over one’s neighborhood. And, of course, these “clean” communities are flush with resources and political power.

Ron Whyte is an environmental activist based in Philadelphia. Photo by Teishka Smith.

Ron Whyte is an environmental activist based in Philadelphia. Photo by Teishka Smith.

Written by Ron Whyte

Editor’s Note: Where waste goes and exists is not a coincidence. This compelling guest blog from Ron Whyte, with Mural Arts Philadelphia, shows how civic participation, public education and systemic thinking can be used together to build power, improve lives and challenge structures that rely on dispossession and oppression, in South Philadelphia.

During its period of post-industrial decline from the mid 1970’s to the early 1990’s, Philadelphia earned the unfortunate nickname of ‘Filthadelphia,’ having become infamous for the trash, litter and dumping that blighted its streets. Yet if we look back in time we will observe that up until the 1950’s Philadelphia was consistently ranked as one of the cleanest cities in the country. In fact, Benjamin Franklin organized the very first street sweeping program during the colonial era, right here in Philadelphia in the 1750’s. In 1917, Philadelphia was one of the first U.S. cities to deploy modern street sweeping technology. So, what changed between the 1950’s and the mid-late 1970’s? The answer to this question reveals a layer of complexity that is almost never associated with the seemingly simple and straightforward issue of trash.

Left, 1937 Philadelphia redlining map; Right, 2018 Philadelphia Litter Index

By the 1950’s, Philadelphia was undergoing the same demographic shifts as other major cities. These changes were driven by one of the largest internal migrations in world history — The Great Migration. Between 1910 and 1970, around six million Black people packed up and fled the poverty, oppression, segregation and racial terror of the Jim Crow South. These internally displaced persons, or refugees, ran into the arms of a less overtly violent, but no less insidious form of systemic racism here in the North. The chronic trash, blight and social dysfunction that plagues low income communities of color in our major cities is a reflection of the systematic disenfranchisement and environmental racism these communities have been subjected to

Trash Academy (a program of Mural Arts Philadelphia’s Environmental Justice Institute) will not approach the issue of trash and litter in urban neighborhoods without putting the situation in its proper historical and socio-political context.

Our recent education and awareness campaign on the benefits of reusable bags is an example of our praxis in action. Single use plastic bags are being banned in cities across the country and around the world, and when we were invited to join a coalition of environmental non-profits and community groups taking action on this issue here in Philadelphia, we welcomed the opportunity. Our unique blend of art, activism and community advocacy was an integral part of the process that led to legislation to ban plastic bags here in Philadelphia. Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, implementation of the ban was delayed until 2021. The state legislature has also passed legislation to interfere in the city’s power to enact the ban Nevertheless, for the young people in our cohort especially, this win was a validation of sorts and yet more proof that art has a crucial role to play in social movements.

We complicate the issue of trash. We recognize that we cannot address the trash issue without acknowledging pre-existing systems of exploitation and oppression. We recognize that mitigation strategies must flow organically from those who have the lived experience of struggling day to day with the problem we’re attempting to solve. We engage community members in participant-led research, education, advocacy, and civic engagement while creating and testing innovative, grassroots solutions to the issue of trash through a horizontal collaborative process. We also encourage youth leadership, positioning young people to take the lead in educating and transforming their own communities. And, because we’re embedded within Mural Arts, the largest public arts organization in the country, we’re committed to approaching the trash issue through the doorway of art and creativity, utilizing game play, fun and discovery as tools and as springboards for more in depth analysis and conversations.When we see disposable coffee cups clogging up a storm drain, or plastic bags fluttering from tree limbs, our first thought is usually something along the lines of, “ugh, people are so disgusting!” And I must admit that when I first became involved with Trash Academy in 2016 I was someone who viewed the problem of trash, litter and dumping to be primarily one of personal consumption and personal habits. The misconception that we would have cleaner streets if only litter bugs would simply learn to hold onto their trash until they reached a trash can, or if people would just stop throwing trash out of their car windows. In the era of neoliberalism, blaming individuals for systemic social problems is definitely the trend du jour.

When we see disposable coffee cups clogging up a storm drain, or plastic bags fluttering from tree limbs, our first thought is usually something along the lines of, “ugh, people are so disgusting!” And I must admit that when I first became involved with Trash Academy in 2016 I was someone who viewed the problem of trash, litter and dumping to be primarily one of personal consumption and personal habits. The misconception that we would have cleaner streets if only litter bugs would simply learn to hold onto their trash until they reached a trash can, or if people would just stop throwing trash out of their car windows. In the era of neoliberalism, blaming individuals for systemic social problems is definitely the trend du jour.

However, the complication that arises when we attempt to totally shift the blame onto corporations and systems is that residents who desperately want to see the trash go away are constantly noticing the bad habits and behaviors of their neighbors. We have perceived this dynamic through our work in South Philadelphia, where the trash crisis is particularly pronounced. The “in your face” bad behavior (littering, short dumping, neglecting to clean the front of one’s property) helps obscure the larger systemic issues and contributes to finger pointing and horizontal hostility. This dynamic highlights why the trash issue is so particularly thorny; yes, larger systemic issues are driving all of this dysfunction, and yet, individual decisions and our participation in consumer culture are factors that cannot be ignored either.

Educational tools are a key part of how we educate and raise awareness, and we have developed one to specifically address this dichotomy of personal behavior/consumption versus corporate and systemic impacts. We were inspired by the implosion research method pioneered by professor Donna Haraway and introduced to us by design strategist Gamar Markarian. The implosion is a very effective tool for unpacking the hidden complexities embedded within seemingly simple objects. The implosion method sees how every issue, object or reaction is “unpackable.”

Our innovation on the implosion method was to visualize it (with help from lead artist Margaret Kearney). We created a space for collaboration between artists, community members, and activists. Our implosions function as stand-alone educational tools, or, they can be complimented by webinars we have developed in collaboration with community members and youth in our cohort. Our ‘implosion’ project was in large part inspired by events taking place during the initial COVID-19 lockdown, particularly the panic buying of toilet paper. While some have viewed the pandemic as a reason to jettison thoughts of sustainability, we are highlighting the fact that the interwoven crises of climate change, environmental degradation and environmental racism require us to be even more committed to protecting what remains while curbing the destructive impacts of consumer culture.

‘places to which the dispossessed have been banished’

Once the trash issue has been complicated we notice that the places associated with cleanliness are usually populated by certain types of people, while the places associated with grime and disorder are primarily the places to which the dispossessed have been banished. And yet, the places associated with cleanliness are the places from which the majority of the trash is being generated.

Call it capitalism’s detritus, and it’s a global crisis.

Those with privilege have the luxury of not having to interact with the waste they create — it’s ferried away with twice weekly trash pick ups and regular street sweeping and cleaning, or, it’s sent overseas to become a problem for the developing world. It’s no coincidence that polluting fossil fuel projects have inflicted South Philadelphia for generations. And you’ll almost never see trash littering the well manicured lawns and green spaces of the suburbs, but not because the people who live there are cleaner or more conscientious than urban, inner city dwellers. Communities that have not been targeted by the police and flooded with drugs and guns are in a much better position to exercise the kind of community care and solidarity that fosters a sense of belonging and collective ownership over one’s neighborhood. And, of course, these “clean” communities are flush with resources and political power.

Ron Whyte is an environmental activist based in Philadelphia. Photo by Teishka Smith.

Ron Whyte is an environmental activist based in Philadelphia. Photo by Teishka Smith.

Written by Ron Whyte

Editor’s Note: Where waste goes and exists is not a coincidence. This compelling guest blog from Ron Whyte, with Mural Arts Philadelphia, shows how civic participation, public education and systemic thinking can be used together to build power, improve lives and challenge structures that rely on dispossession and oppression, in South Philadelphia.

During its period of post-industrial decline from the mid 1970’s to the early 1990’s, Philadelphia earned the unfortunate nickname of ‘Filthadelphia,’ having become infamous for the trash, litter and dumping that blighted its streets. Yet if we look back in time we will observe that up until the 1950’s Philadelphia was consistently ranked as one of the cleanest cities in the country. In fact, Benjamin Franklin organized the very first street sweeping program during the colonial era, right here in Philadelphia in the 1750’s. In 1917, Philadelphia was one of the first U.S. cities to deploy modern street sweeping technology. So, what changed between the 1950’s and the mid-late 1970’s? The answer to this question reveals a layer of complexity that is almost never associated with the seemingly simple and straightforward issue of trash.

Left, 1937 Philadelphia redlining map; Right, 2018 Philadelphia Litter Index

By the 1950’s, Philadelphia was undergoing the same demographic shifts as other major cities. These changes were driven by one of the largest internal migrations in world history — The Great Migration. Between 1910 and 1970, around six million Black people packed up and fled the poverty, oppression, segregation and racial terror of the Jim Crow South. These internally displaced persons, or refugees, ran into the arms of a less overtly violent, but no less insidious form of systemic racism here in the North. The chronic trash, blight and social dysfunction that plagues low income communities of color in our major cities is a reflection of the systematic disenfranchisement and environmental racism these communities have been subjected to

Trash Academy (a program of Mural Arts Philadelphia’s Environmental Justice Institute) will not approach the issue of trash and litter in urban neighborhoods without putting the situation in its proper historical and socio-political context.

Our recent education and awareness campaign on the benefits of reusable bags is an example of our praxis in action. Single use plastic bags are being banned in cities across the country and around the world, and when we were invited to join a coalition of environmental non-profits and community groups taking action on this issue here in Philadelphia, we welcomed the opportunity. Our unique blend of art, activism and community advocacy was an integral part of the process that led to legislation to ban plastic bags here in Philadelphia. Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, implementation of the ban was delayed until 2021. The state legislature has also passed legislation to interfere in the city’s power to enact the ban Nevertheless, for the young people in our cohort especially, this win was a validation of sorts and yet more proof that art has a crucial role to play in social movements.

We complicate the issue of trash. We recognize that we cannot address the trash issue without acknowledging pre-existing systems of exploitation and oppression. We recognize that mitigation strategies must flow organically from those who have the lived experience of struggling day to day with the problem we’re attempting to solve. We engage community members in participant-led research, education, advocacy, and civic engagement while creating and testing innovative, grassroots solutions to the issue of trash through a horizontal collaborative process. We also encourage youth leadership, positioning young people to take the lead in educating and transforming their own communities. And, because we’re embedded within Mural Arts, the largest public arts organization in the country, we’re committed to approaching the trash issue through the doorway of art and creativity, utilizing game play, fun and discovery as tools and as springboards for more in depth analysis and conversations.When we see disposable coffee cups clogging up a storm drain, or plastic bags fluttering from tree limbs, our first thought is usually something along the lines of, “ugh, people are so disgusting!” And I must admit that when I first became involved with Trash Academy in 2016 I was someone who viewed the problem of trash, litter and dumping to be primarily one of personal consumption and personal habits. The misconception that we would have cleaner streets if only litter bugs would simply learn to hold onto their trash until they reached a trash can, or if people would just stop throwing trash out of their car windows. In the era of neoliberalism, blaming individuals for systemic social problems is definitely the trend du jour.

When we see disposable coffee cups clogging up a storm drain, or plastic bags fluttering from tree limbs, our first thought is usually something along the lines of, “ugh, people are so disgusting!” And I must admit that when I first became involved with Trash Academy in 2016 I was someone who viewed the problem of trash, litter and dumping to be primarily one of personal consumption and personal habits. The misconception that we would have cleaner streets if only litter bugs would simply learn to hold onto their trash until they reached a trash can, or if people would just stop throwing trash out of their car windows. In the era of neoliberalism, blaming individuals for systemic social problems is definitely the trend du jour.

However, the complication that arises when we attempt to totally shift the blame onto corporations and systems is that residents who desperately want to see the trash go away are constantly noticing the bad habits and behaviors of their neighbors. We have perceived this dynamic through our work in South Philadelphia, where the trash crisis is particularly pronounced. The “in your face” bad behavior (littering, short dumping, neglecting to clean the front of one’s property) helps obscure the larger systemic issues and contributes to finger pointing and horizontal hostility. This dynamic highlights why the trash issue is so particularly thorny; yes, larger systemic issues are driving all of this dysfunction, and yet, individual decisions and our participation in consumer culture are factors that cannot be ignored either.

Educational tools are a key part of how we educate and raise awareness, and we have developed one to specifically address this dichotomy of personal behavior/consumption versus corporate and systemic impacts. We were inspired by the implosion research method pioneered by professor Donna Haraway and introduced to us by design strategist Gamar Markarian. The implosion is a very effective tool for unpacking the hidden complexities embedded within seemingly simple objects. The implosion method sees how every issue, object or reaction is “unpackable.”

Our innovation on the implosion method was to visualize it (with help from lead artist Margaret Kearney). We created a space for collaboration between artists, community members, and activists. Our implosions function as stand-alone educational tools, or, they can be complimented by webinars we have developed in collaboration with community members and youth in our cohort. Our ‘implosion’ project was in large part inspired by events taking place during the initial COVID-19 lockdown, particularly the panic buying of toilet paper. While some have viewed the pandemic as a reason to jettison thoughts of sustainability, we are highlighting the fact that the interwoven crises of climate change, environmental degradation and environmental racism require us to be even more committed to protecting what remains while curbing the destructive impacts of consumer culture.

‘places to which the dispossessed have been banished’

Once the trash issue has been complicated we notice that the places associated with cleanliness are usually populated by certain types of people, while the places associated with grime and disorder are primarily the places to which the dispossessed have been banished. And yet, the places associated with cleanliness are the places from which the majority of the trash is being generated.

Call it capitalism’s detritus, and it’s a global crisis.

Those with privilege have the luxury of not having to interact with the waste they create — it’s ferried away with twice weekly trash pick ups and regular street sweeping and cleaning, or, it’s sent overseas to become a problem for the developing world. It’s no coincidence that polluting fossil fuel projects have inflicted South Philadelphia for generations. And you’ll almost never see trash littering the well manicured lawns and green spaces of the suburbs, but not because the people who live there are cleaner or more conscientious than urban, inner city dwellers. Communities that have not been targeted by the police and flooded with drugs and guns are in a much better position to exercise the kind of community care and solidarity that fosters a sense of belonging and collective ownership over one’s neighborhood. And, of course, these “clean” communities are flush with resources and political power.

Ron Whyte is an environmental activist based in Philadelphia. Photo by Teishka Smith.

Ron Whyte is an environmental activist based in Philadelphia. Photo by Teishka Smith.

Written by Ron Whyte

Editor’s Note: Where waste goes and exists is not a coincidence. This compelling guest blog from Ron Whyte, with Mural Arts Philadelphia, shows how civic participation, public education and systemic thinking can be used together to build power, improve lives and challenge structures that rely on dispossession and oppression, in South Philadelphia.

During its period of post-industrial decline from the mid 1970’s to the early 1990’s, Philadelphia earned the unfortunate nickname of ‘Filthadelphia,’ having become infamous for the trash, litter and dumping that blighted its streets. Yet if we look back in time we will observe that up until the 1950’s Philadelphia was consistently ranked as one of the cleanest cities in the country. In fact, Benjamin Franklin organized the very first street sweeping program during the colonial era, right here in Philadelphia in the 1750’s. In 1917, Philadelphia was one of the first U.S. cities to deploy modern street sweeping technology. So, what changed between the 1950’s and the mid-late 1970’s? The answer to this question reveals a layer of complexity that is almost never associated with the seemingly simple and straightforward issue of trash.

Left, 1937 Philadelphia redlining map; Right, 2018 Philadelphia Litter Index

By the 1950’s, Philadelphia was undergoing the same demographic shifts as other major cities. These changes were driven by one of the largest internal migrations in world history — The Great Migration. Between 1910 and 1970, around six million Black people packed up and fled the poverty, oppression, segregation and racial terror of the Jim Crow South. These internally displaced persons, or refugees, ran into the arms of a less overtly violent, but no less insidious form of systemic racism here in the North. The chronic trash, blight and social dysfunction that plagues low income communities of color in our major cities is a reflection of the systematic disenfranchisement and environmental racism these communities have been subjected to

Trash Academy (a program of Mural Arts Philadelphia’s Environmental Justice Institute) will not approach the issue of trash and litter in urban neighborhoods without putting the situation in its proper historical and socio-political context.

Our recent education and awareness campaign on the benefits of reusable bags is an example of our praxis in action. Single use plastic bags are being banned in cities across the country and around the world, and when we were invited to join a coalition of environmental non-profits and community groups taking action on this issue here in Philadelphia, we welcomed the opportunity. Our unique blend of art, activism and community advocacy was an integral part of the process that led to legislation to ban plastic bags here in Philadelphia. Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, implementation of the ban was delayed until 2021. The state legislature has also passed legislation to interfere in the city’s power to enact the ban Nevertheless, for the young people in our cohort especially, this win was a validation of sorts and yet more proof that art has a crucial role to play in social movements.

We complicate the issue of trash. We recognize that we cannot address the trash issue without acknowledging pre-existing systems of exploitation and oppression. We recognize that mitigation strategies must flow organically from those who have the lived experience of struggling day to day with the problem we’re attempting to solve. We engage community members in participant-led research, education, advocacy, and civic engagement while creating and testing innovative, grassroots solutions to the issue of trash through a horizontal collaborative process. We also encourage youth leadership, positioning young people to take the lead in educating and transforming their own communities. And, because we’re embedded within Mural Arts, the largest public arts organization in the country, we’re committed to approaching the trash issue through the doorway of art and creativity, utilizing game play, fun and discovery as tools and as springboards for more in depth analysis and conversations.When we see disposable coffee cups clogging up a storm drain, or plastic bags fluttering from tree limbs, our first thought is usually something along the lines of, “ugh, people are so disgusting!” And I must admit that when I first became involved with Trash Academy in 2016 I was someone who viewed the problem of trash, litter and dumping to be primarily one of personal consumption and personal habits. The misconception that we would have cleaner streets if only litter bugs would simply learn to hold onto their trash until they reached a trash can, or if people would just stop throwing trash out of their car windows. In the era of neoliberalism, blaming individuals for systemic social problems is definitely the trend du jour.

When we see disposable coffee cups clogging up a storm drain, or plastic bags fluttering from tree limbs, our first thought is usually something along the lines of, “ugh, people are so disgusting!” And I must admit that when I first became involved with Trash Academy in 2016 I was someone who viewed the problem of trash, litter and dumping to be primarily one of personal consumption and personal habits. The misconception that we would have cleaner streets if only litter bugs would simply learn to hold onto their trash until they reached a trash can, or if people would just stop throwing trash out of their car windows. In the era of neoliberalism, blaming individuals for systemic social problems is definitely the trend du jour.

However, the complication that arises when we attempt to totally shift the blame onto corporations and systems is that residents who desperately want to see the trash go away are constantly noticing the bad habits and behaviors of their neighbors. We have perceived this dynamic through our work in South Philadelphia, where the trash crisis is particularly pronounced. The “in your face” bad behavior (littering, short dumping, neglecting to clean the front of one’s property) helps obscure the larger systemic issues and contributes to finger pointing and horizontal hostility. This dynamic highlights why the trash issue is so particularly thorny; yes, larger systemic issues are driving all of this dysfunction, and yet, individual decisions and our participation in consumer culture are factors that cannot be ignored either.

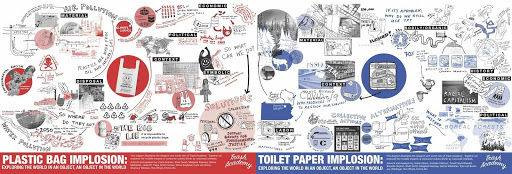

Educational tools are a key part of how we educate and raise awareness, and we have developed one to specifically address this dichotomy of personal behavior/consumption versus corporate and systemic impacts. We were inspired by the implosion research method pioneered by professor Donna Haraway and introduced to us by design strategist Gamar Markarian. The implosion is a very effective tool for unpacking the hidden complexities embedded within seemingly simple objects. The implosion method sees how every issue, object or reaction is “unpackable.”

Our innovation on the implosion method was to visualize it (with help from lead artist Margaret Kearney). We created a space for collaboration between artists, community members, and activists. Our implosions function as stand-alone educational tools, or, they can be complimented by webinars we have developed in collaboration with community members and youth in our cohort. Our ‘implosion’ project was in large part inspired by events taking place during the initial COVID-19 lockdown, particularly the panic buying of toilet paper. While some have viewed the pandemic as a reason to jettison thoughts of sustainability, we are highlighting the fact that the interwoven crises of climate change, environmental degradation and environmental racism require us to be even more committed to protecting what remains while curbing the destructive impacts of consumer culture.

‘places to which the dispossessed have been banished’

Once the trash issue has been complicated we notice that the places associated with cleanliness are usually populated by certain types of people, while the places associated with grime and disorder are primarily the places to which the dispossessed have been banished. And yet, the places associated with cleanliness are the places from which the majority of the trash is being generated.

Call it capitalism’s detritus, and it’s a global crisis.

Those with privilege have the luxury of not having to interact with the waste they create — it’s ferried away with twice weekly trash pick ups and regular street sweeping and cleaning, or, it’s sent overseas to become a problem for the developing world. It’s no coincidence that polluting fossil fuel projects have inflicted South Philadelphia for generations. And you’ll almost never see trash littering the well manicured lawns and green spaces of the suburbs, but not because the people who live there are cleaner or more conscientious than urban, inner city dwellers. Communities that have not been targeted by the police and flooded with drugs and guns are in a much better position to exercise the kind of community care and solidarity that fosters a sense of belonging and collective ownership over one’s neighborhood. And, of course, these “clean” communities are flush with resources and political power.

Ron Whyte is an environmental activist based in Philadelphia. Photo by Teishka Smith.

Ron Whyte is an environmental activist based in Philadelphia. Photo by Teishka Smith.

Written by Ron Whyte

Editor’s Note: Where waste goes and exists is not a coincidence. This compelling guest blog from Ron Whyte, with Mural Arts Philadelphia, shows how civic participation, public education and systemic thinking can be used together to build power, improve lives and challenge structures that rely on dispossession and oppression, in South Philadelphia.

During its period of post-industrial decline from the mid 1970’s to the early 1990’s, Philadelphia earned the unfortunate nickname of ‘Filthadelphia,’ having become infamous for the trash, litter and dumping that blighted its streets. Yet if we look back in time we will observe that up until the 1950’s Philadelphia was consistently ranked as one of the cleanest cities in the country. In fact, Benjamin Franklin organized the very first street sweeping program during the colonial era, right here in Philadelphia in the 1750’s. In 1917, Philadelphia was one of the first U.S. cities to deploy modern street sweeping technology. So, what changed between the 1950’s and the mid-late 1970’s? The answer to this question reveals a layer of complexity that is almost never associated with the seemingly simple and straightforward issue of trash.

Left, 1937 Philadelphia redlining map; Right, 2018 Philadelphia Litter Index

By the 1950’s, Philadelphia was undergoing the same demographic shifts as other major cities. These changes were driven by one of the largest internal migrations in world history — The Great Migration. Between 1910 and 1970, around six million Black people packed up and fled the poverty, oppression, segregation and racial terror of the Jim Crow South. These internally displaced persons, or refugees, ran into the arms of a less overtly violent, but no less insidious form of systemic racism here in the North. The chronic trash, blight and social dysfunction that plagues low income communities of color in our major cities is a reflection of the systematic disenfranchisement and environmental racism these communities have been subjected to

Trash Academy (a program of Mural Arts Philadelphia’s Environmental Justice Institute) will not approach the issue of trash and litter in urban neighborhoods without putting the situation in its proper historical and socio-political context.

Our recent education and awareness campaign on the benefits of reusable bags is an example of our praxis in action. Single use plastic bags are being banned in cities across the country and around the world, and when we were invited to join a coalition of environmental non-profits and community groups taking action on this issue here in Philadelphia, we welcomed the opportunity. Our unique blend of art, activism and community advocacy was an integral part of the process that led to legislation to ban plastic bags here in Philadelphia. Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, implementation of the ban was delayed until 2021. The state legislature has also passed legislation to interfere in the city’s power to enact the ban Nevertheless, for the young people in our cohort especially, this win was a validation of sorts and yet more proof that art has a crucial role to play in social movements.

We complicate the issue of trash. We recognize that we cannot address the trash issue without acknowledging pre-existing systems of exploitation and oppression. We recognize that mitigation strategies must flow organically from those who have the lived experience of struggling day to day with the problem we’re attempting to solve. We engage community members in participant-led research, education, advocacy, and civic engagement while creating and testing innovative, grassroots solutions to the issue of trash through a horizontal collaborative process. We also encourage youth leadership, positioning young people to take the lead in educating and transforming their own communities. And, because we’re embedded within Mural Arts, the largest public arts organization in the country, we’re committed to approaching the trash issue through the doorway of art and creativity, utilizing game play, fun and discovery as tools and as springboards for more in depth analysis and conversations.When we see disposable coffee cups clogging up a storm drain, or plastic bags fluttering from tree limbs, our first thought is usually something along the lines of, “ugh, people are so disgusting!” And I must admit that when I first became involved with Trash Academy in 2016 I was someone who viewed the problem of trash, litter and dumping to be primarily one of personal consumption and personal habits. The misconception that we would have cleaner streets if only litter bugs would simply learn to hold onto their trash until they reached a trash can, or if people would just stop throwing trash out of their car windows. In the era of neoliberalism, blaming individuals for systemic social problems is definitely the trend du jour.

When we see disposable coffee cups clogging up a storm drain, or plastic bags fluttering from tree limbs, our first thought is usually something along the lines of, “ugh, people are so disgusting!” And I must admit that when I first became involved with Trash Academy in 2016 I was someone who viewed the problem of trash, litter and dumping to be primarily one of personal consumption and personal habits. The misconception that we would have cleaner streets if only litter bugs would simply learn to hold onto their trash until they reached a trash can, or if people would just stop throwing trash out of their car windows. In the era of neoliberalism, blaming individuals for systemic social problems is definitely the trend du jour.

However, the complication that arises when we attempt to totally shift the blame onto corporations and systems is that residents who desperately want to see the trash go away are constantly noticing the bad habits and behaviors of their neighbors. We have perceived this dynamic through our work in South Philadelphia, where the trash crisis is particularly pronounced. The “in your face” bad behavior (littering, short dumping, neglecting to clean the front of one’s property) helps obscure the larger systemic issues and contributes to finger pointing and horizontal hostility. This dynamic highlights why the trash issue is so particularly thorny; yes, larger systemic issues are driving all of this dysfunction, and yet, individual decisions and our participation in consumer culture are factors that cannot be ignored either.

Educational tools are a key part of how we educate and raise awareness, and we have developed one to specifically address this dichotomy of personal behavior/consumption versus corporate and systemic impacts. We were inspired by the implosion research method pioneered by professor Donna Haraway and introduced to us by design strategist Gamar Markarian. The implosion is a very effective tool for unpacking the hidden complexities embedded within seemingly simple objects. The implosion method sees how every issue, object or reaction is “unpackable.”

Our innovation on the implosion method was to visualize it (with help from lead artist Margaret Kearney). We created a space for collaboration between artists, community members, and activists. Our implosions function as stand-alone educational tools, or, they can be complimented by webinars we have developed in collaboration with community members and youth in our cohort. Our ‘implosion’ project was in large part inspired by events taking place during the initial COVID-19 lockdown, particularly the panic buying of toilet paper. While some have viewed the pandemic as a reason to jettison thoughts of sustainability, we are highlighting the fact that the interwoven crises of climate change, environmental degradation and environmental racism require us to be even more committed to protecting what remains while curbing the destructive impacts of consumer culture.

‘places to which the dispossessed have been banished’

Once the trash issue has been complicated we notice that the places associated with cleanliness are usually populated by certain types of people, while the places associated with grime and disorder are primarily the places to which the dispossessed have been banished. And yet, the places associated with cleanliness are the places from which the majority of the trash is being generated.

Call it capitalism’s detritus, and it’s a global crisis.

Those with privilege have the luxury of not having to interact with the waste they create — it’s ferried away with twice weekly trash pick ups and regular street sweeping and cleaning, or, it’s sent overseas to become a problem for the developing world. It’s no coincidence that polluting fossil fuel projects have inflicted South Philadelphia for generations. And you’ll almost never see trash littering the well manicured lawns and green spaces of the suburbs, but not because the people who live there are cleaner or more conscientious than urban, inner city dwellers. Communities that have not been targeted by the police and flooded with drugs and guns are in a much better position to exercise the kind of community care and solidarity that fosters a sense of belonging and collective ownership over one’s neighborhood. And, of course, these “clean” communities are flush with resources and political power.

Ron Whyte is an environmental activist based in Philadelphia. Photo by Teishka Smith.

Ron Whyte is an environmental activist based in Philadelphia. Photo by Teishka Smith.

Written by Ron Whyte

Editor’s Note: Where waste goes and exists is not a coincidence. This compelling guest blog from Ron Whyte, with Mural Arts Philadelphia, shows how civic participation, public education and systemic thinking can be used together to build power, improve lives and challenge structures that rely on dispossession and oppression, in South Philadelphia.

During its period of post-industrial decline from the mid 1970’s to the early 1990’s, Philadelphia earned the unfortunate nickname of ‘Filthadelphia,’ having become infamous for the trash, litter and dumping that blighted its streets. Yet if we look back in time we will observe that up until the 1950’s Philadelphia was consistently ranked as one of the cleanest cities in the country. In fact, Benjamin Franklin organized the very first street sweeping program during the colonial era, right here in Philadelphia in the 1750’s. In 1917, Philadelphia was one of the first U.S. cities to deploy modern street sweeping technology. So, what changed between the 1950’s and the mid-late 1970’s? The answer to this question reveals a layer of complexity that is almost never associated with the seemingly simple and straightforward issue of trash.

Left, 1937 Philadelphia redlining map; Right, 2018 Philadelphia Litter Index

By the 1950’s, Philadelphia was undergoing the same demographic shifts as other major cities. These changes were driven by one of the largest internal migrations in world history — The Great Migration. Between 1910 and 1970, around six million Black people packed up and fled the poverty, oppression, segregation and racial terror of the Jim Crow South. These internally displaced persons, or refugees, ran into the arms of a less overtly violent, but no less insidious form of systemic racism here in the North. The chronic trash, blight and social dysfunction that plagues low income communities of color in our major cities is a reflection of the systematic disenfranchisement and environmental racism these communities have been subjected to

Trash Academy (a program of Mural Arts Philadelphia’s Environmental Justice Institute) will not approach the issue of trash and litter in urban neighborhoods without putting the situation in its proper historical and socio-political context.

Our recent education and awareness campaign on the benefits of reusable bags is an example of our praxis in action. Single use plastic bags are being banned in cities across the country and around the world, and when we were invited to join a coalition of environmental non-profits and community groups taking action on this issue here in Philadelphia, we welcomed the opportunity. Our unique blend of art, activism and community advocacy was an integral part of the process that led to legislation to ban plastic bags here in Philadelphia. Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, implementation of the ban was delayed until 2021. The state legislature has also passed legislation to interfere in the city’s power to enact the ban Nevertheless, for the young people in our cohort especially, this win was a validation of sorts and yet more proof that art has a crucial role to play in social movements.

We complicate the issue of trash. We recognize that we cannot address the trash issue without acknowledging pre-existing systems of exploitation and oppression. We recognize that mitigation strategies must flow organically from those who have the lived experience of struggling day to day with the problem we’re attempting to solve. We engage community members in participant-led research, education, advocacy, and civic engagement while creating and testing innovative, grassroots solutions to the issue of trash through a horizontal collaborative process. We also encourage youth leadership, positioning young people to take the lead in educating and transforming their own communities. And, because we’re embedded within Mural Arts, the largest public arts organization in the country, we’re committed to approaching the trash issue through the doorway of art and creativity, utilizing game play, fun and discovery as tools and as springboards for more in depth analysis and conversations.When we see disposable coffee cups clogging up a storm drain, or plastic bags fluttering from tree limbs, our first thought is usually something along the lines of, “ugh, people are so disgusting!” And I must admit that when I first became involved with Trash Academy in 2016 I was someone who viewed the problem of trash, litter and dumping to be primarily one of personal consumption and personal habits. The misconception that we would have cleaner streets if only litter bugs would simply learn to hold onto their trash until they reached a trash can, or if people would just stop throwing trash out of their car windows. In the era of neoliberalism, blaming individuals for systemic social problems is definitely the trend du jour.

When we see disposable coffee cups clogging up a storm drain, or plastic bags fluttering from tree limbs, our first thought is usually something along the lines of, “ugh, people are so disgusting!” And I must admit that when I first became involved with Trash Academy in 2016 I was someone who viewed the problem of trash, litter and dumping to be primarily one of personal consumption and personal habits. The misconception that we would have cleaner streets if only litter bugs would simply learn to hold onto their trash until they reached a trash can, or if people would just stop throwing trash out of their car windows. In the era of neoliberalism, blaming individuals for systemic social problems is definitely the trend du jour.

However, the complication that arises when we attempt to totally shift the blame onto corporations and systems is that residents who desperately want to see the trash go away are constantly noticing the bad habits and behaviors of their neighbors. We have perceived this dynamic through our work in South Philadelphia, where the trash crisis is particularly pronounced. The “in your face” bad behavior (littering, short dumping, neglecting to clean the front of one’s property) helps obscure the larger systemic issues and contributes to finger pointing and horizontal hostility. This dynamic highlights why the trash issue is so particularly thorny; yes, larger systemic issues are driving all of this dysfunction, and yet, individual decisions and our participation in consumer culture are factors that cannot be ignored either.

Educational tools are a key part of how we educate and raise awareness, and we have developed one to specifically address this dichotomy of personal behavior/consumption versus corporate and systemic impacts. We were inspired by the implosion research method pioneered by professor Donna Haraway and introduced to us by design strategist Gamar Markarian. The implosion is a very effective tool for unpacking the hidden complexities embedded within seemingly simple objects. The implosion method sees how every issue, object or reaction is “unpackable.”

Our innovation on the implosion method was to visualize it (with help from lead artist Margaret Kearney). We created a space for collaboration between artists, community members, and activists. Our implosions function as stand-alone educational tools, or, they can be complimented by webinars we have developed in collaboration with community members and youth in our cohort. Our ‘implosion’ project was in large part inspired by events taking place during the initial COVID-19 lockdown, particularly the panic buying of toilet paper. While some have viewed the pandemic as a reason to jettison thoughts of sustainability, we are highlighting the fact that the interwoven crises of climate change, environmental degradation and environmental racism require us to be even more committed to protecting what remains while curbing the destructive impacts of consumer culture.

‘places to which the dispossessed have been banished’

Once the trash issue has been complicated we notice that the places associated with cleanliness are usually populated by certain types of people, while the places associated with grime and disorder are primarily the places to which the dispossessed have been banished. And yet, the places associated with cleanliness are the places from which the majority of the trash is being generated.

Call it capitalism’s detritus, and it’s a global crisis.

Those with privilege have the luxury of not having to interact with the waste they create — it’s ferried away with twice weekly trash pick ups and regular street sweeping and cleaning, or, it’s sent overseas to become a problem for the developing world. It’s no coincidence that polluting fossil fuel projects have inflicted South Philadelphia for generations. And you’ll almost never see trash littering the well manicured lawns and green spaces of the suburbs, but not because the people who live there are cleaner or more conscientious than urban, inner city dwellers. Communities that have not been targeted by the police and flooded with drugs and guns are in a much better position to exercise the kind of community care and solidarity that fosters a sense of belonging and collective ownership over one’s neighborhood. And, of course, these “clean” communities are flush with resources and political power.

Ron Whyte is an environmental activist based in Philadelphia. Photo by Teishka Smith.

Ron Whyte is an environmental activist based in Philadelphia. Photo by Teishka Smith.