Written by Kira Kelly and Simon Davis-Cohen

Power offers concessions only to its most privileged opponents, concedes nothing without a demand, and blunts any tool it offers to the general public

One hundred years ago, the 19th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution was ratified, purporting to grant women the right to vote in the United States. In reality, this right applied only to white women; explicitly racist laws during and beyond the Jim Crow era categorically prohibited Black people from voting, and kept Indigenous and many Asian, Middle Eastern, and Latinx people from obtaining citizenship. Even after courts struck down overtly discriminatory measures, “neutral” restrictions rooted in racism evolved to nonetheless continue depriving many women of meaningful access to the polls.

The 19th Amendment benefited white women almost exclusively, to the detriment of women of color. Many revolutionary Black women dedicated their lives to the suffragette movement in the early 20th century, only to have white suffragette leaders erase their names from accounts of movement history, silence their demands for anti-racism as a necessary component of feminism, and accept the establishment’s offer to make voting accessible mainly to white, affluent women.

Key Lessons from the Suffragettes

Suffragette activists offer many lessons to modern social and environmental justice movements. First, we will never achieve justice or equality when the most privileged subsect of an oppressed group withdraws its outrage from the movement in exchange for mainstream recognition. Second, a marginalized group cannot make structural change by channeling its energy into rigidly controlled and deliberately ineffective mechanisms for change.

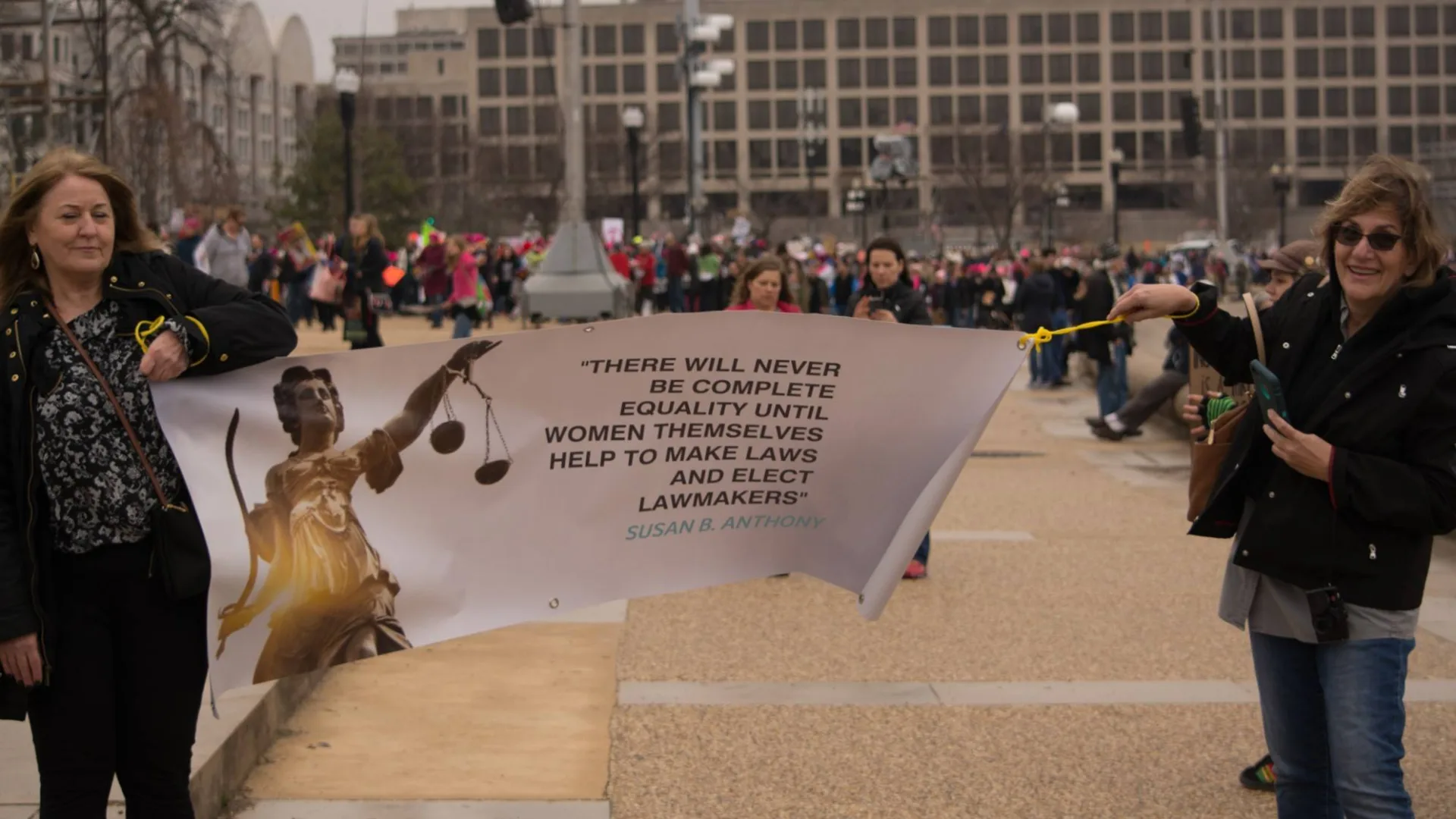

Men did not voluntarily vote to extend political access to women. To pressure the system that excluded them, suffragettes exercised their inherent right to vote without waiting for the government to give them permission, and used a wide range of organizing and movement building tools to force federal changes. Women illegally voted. They marched, they picketed. They held parades, pageants, and other mass gatherings. They went on hunger (and intimacy) strikes. They pushed for local and state laws that gave women the right to vote before the federal government would. They “rioted.” Many served jail time for these activities.

Thinking Outside the Box

To gain recognition from a system that does not recognize your full personhood demands tactics that fall outside that system’s own proscribed mechanisms for change. You can’t vote to get the right to vote. Furthermore, anything that voting alone can accomplish will necessarily be within the range of options the existing corporate state is willing to offer.

This is not to deny or discredit the importance of voting, or of safeguarding the right to vote against ongoing gerrymandering and voting restrictions white, wealthy, cisgender men and their affiliated corporate interests have designed to dilute Black, brown, poor, incarcerated, immigrant, transgender and other voices. Voting in the current presidential election is an opportunity to reject an overt, explicit white supremacist in favor of a passively racist moderate who authored the Crime Bill but at least does not embolden legions of vigilante neo-Nazis to crawl out of the woodworks. State and local elections offer greater variety in candidates and agendas. Municipal ballots, particularly those containing voter-initiative petitions, can be tools for advancing radical and necessary liberatory change.

Suffragettes Would Implore Us to Do More Than Vote

Media hype and national discourse intentionally emphasize voting as the end-all-be-all to end injustice. This conversation deserves more nuance. Yes, vote. And of course, take action against the racist, classist, ableist politicians seeking to restrict certain people from voting. But also know that the vote was won using outside-the-system tactics. Getting what we need today requires similar organizing methods. Lastly, recognize that as access to the right to participate in government expands to new classes of people, that same government weakens the power that this access conveys.

When formerly enslaved men were granted the right to vote, not only was Jim Crow lawmaking and violence unleashed on the African American population, but simultaneously a new legal doctrine to grant white-controlled corporations “personhood” was invented soon after—out of thin air—to protect the ruling class from the redistributive potential that accompanied the expansion of suffrage.

Restrictions on What Can Be Voted On

Today, when voters attempt to utilize their voting power through direct democracy on behalf of people, asserting our basic needs and resisting the exploitation of people and the environment, the status quo again tries to quelch meaningful influence over society. Your vote can only go so far, we are often told.

Curbs on corporate campaign contributions, millionaires’ taxes, limits on police power, opposition to the fossil fuel industry, minimum wage increases—virtually all pressing societal issues—have been advanced through local and statewide ballot measures in recent years. However, we see that governing officials will refuse to put these initiatives on the ballot despite residents following all necessary procedures, or refuse to recognize and enforce them once adopted.

When people are able to vote on and pass these protective local laws, corporations and states often sue to overturn the vote and intimidate potential copycats. Instead, we are told to choose between two or three candidates at the next election, to let them make the decisions for us. And we know whose interests this system serves.

In 2014, Cambridge University Press published a study that found corporations’ influence over policy is so severe in the United States that the country can be accurately called a “civil oligarchy.” It found that “economic elites and organised groups representing business interests have substantial independent impacts on US government policy, while average citizens and mass-based interest groups have little or no independent influence.”

Passing Extra-legal Laws is Part of a Movement

While corporations dictate the substance of laws and regulations and use their legal standing and political power to control judicial decisions, legislators and judges carefully limit what people are allowed to vote on. Gatekeepers say that because voter initiative ballot measures challenge existing law, the public must not be allowed to vote on them. However, we can force governments to treat public interest laws as valid, viable exercises of our inherent right to self government—if we apply enough pressure.

The suffragette’s diversity of tactics successfully applied this pressure 100 years ago, forcing state and local governments to hold votes on 54 state ballot measures to expand suffrage to women. At that time, it was unconstitutional to allow women to vote. However, the extra-legal element of these measures moved the political conditions that led to the 19th Amendment.

Today it is similarly unconstitutional to tax millionaires in some states, but this must not mean people should be denied the right to vote on the issue (as has happened in Massachusetts and Arizona). Blocking the opportunity for people to vote on a liberatory measure also stifles their political education on that subject. Examples of this are multitude over just the past five years.

We are not here to say voting does not matter or does not make a difference. We are taking a macro perspective to say that the vote has been diluted. A body of law and political maneuvering that protects white corporate power from the masses weakens the suffrage that civil rights movements have won with blood and tears. We must continue our efforts to defend (and expand) the franchise, not only to guard against voter exclusion but also to expand the power and jurisdiction of the vote. Voter initiatives of any substance cannot vote themselves into effect without a movement behind them. To build this movement, we must be critical of the tools offered by institutions who benefit from giving us foam mallets instead of hammers. We must be open to trying tools we may have never seen or used before.

As our colleague at the Community Environmental Legal Defense Fund Ben Price writes, United States history has been defined in part by forces that “privatize control over who will and who will not vote, and whether the votes that are cast can have any effect on policy and power.” On the 100th Anniversary of the 19th Amendment, we reflect on how private forces have defined the past century as one of racism, ecological destruction, and bigotry. With this reflection comes a commitment to reject the limits that private forces place on our ability to govern ourselves. We, the people, must be the force that defines our future.

This piece was originally published here by Common Dreams.