Last week, ten South Florida cities sued the State of Florida in a legal challenge to the Joe Carlucci Uniform Firearms Act. Originally adopted in 1987 by state legislators, the law established state primacy over the regulation of firearms within the state. It declares that the state:

“occupies the whole field of regulation of firearms and ammunition, including the purchase, sale, transfer, taxation, manufacture, ownership, possession, storage, and transportation thereof, to the exclusion of all existing and future county, city, town, or municipal ordinances. . . Any such existing ordinances, rules, or regulations are hereby declared null and void.”

In June, 2011, in an effort backed by the National Rifle Association (NRA) and an open-carry advocacy group known as “Florida Carry,” the Act was amended by state legislators. They added new provisions that punish local elected officials who vote to adopt gun control laws. The law now provides that the Governor may “remove” from office any local elected official who “enacts or enforces” a local ordinance that is preempted; that a court can assess a “civil fine of up to $5,000 against the elected official,” which must be paid personally by the official; and that any “person or organization whose membership is adversely affected” by the municipal law may recover up to $100,000 against the municipality.

State Enforcement of Preemption Laws

The passage of state preemptive laws is commonplace. However, what’s unusual about the Florida law, and several laws that preceded it, is the state’s use of preemption to enforce the laws. The state is adding provisions that: 1. encourage and reward private parties to punish those elected officials who dare to challenge the state’s preemptive reach, or 2. insert the state directly into the business of enforcement – as Florida has done by authorizing civil penalties and the removal of elected officials by the Governor.

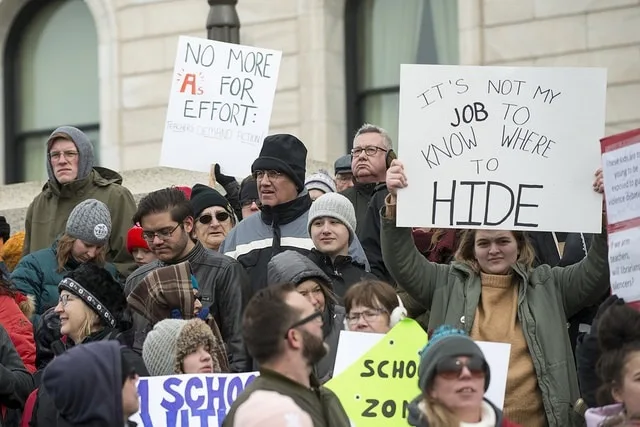

Ten Florida cities have filed suit against the state, in an action known as City of Weston v. Scott. The cities contend that:

- the punishment provisions of Florida’s preemption law unconstitutionally expand the Governor’s powers to include removal of municipal officials,

- the Act infringes on the immunity provided to elected officials when they act in a legislative capacity, and

- the Act violates the free speech rights of those officials by controlling what they discuss and adopt at the municipal level.

All of those are good arguments, of course, for challenging the ways in which the state punishes elected officials for running afoul of state preemptive law. It does not, however, directly challenge the authority of the State to prohibit them from adopting gun control laws in the first place.

“Look Ma, No Hands!”

Direct state involvement in the enforcement of preemption laws used to be a rare occurrence. What hasn’t been rare, unfortunately, is state legislators using preemption laws to shield large economic actors from municipal lawmaking. This gives private corporations an additional tool to use to sue those municipal governments who “interfere” with the corporation’s activities.

By passing preemption laws but not having a direct hand in enforcement of them, state legislators can claim political deniability when municipal laws are struck down. Because the plaintiffs in the enforcement cases are the private companies rather than the state, the state’s role gets lost in the shuffle.

In this “look ma, no hands” game of preemption, the villain becomes the corporation that sues the community, rather than the state. Yet it was the state that enabled the corporation to do so in the first place.

Authority Reserved for the [Corporate] State: Some Examples

State oil and gas laws provide a good example. Almost all state legislatures have declared that oil and gas extraction is an area reserved exclusively for state regulation. Most of those state oil and gas laws thus provide that no city or other municipality shall adopt any law regulating oil and gas extraction. Oil and gas companies affected by those local laws can then enforce state preemptive laws against the municipality in court. The inevitable outcome is the nullification of the municipal law.

Along with oil and gas laws, state legislatures have used preemption to benefit a vast spectrum of corporations. Those laws range from protecting agribusiness corporations by preempting local governments from banning genetically modified seeds and large water withdrawals, to protecting corporate employers and developers by preempting local governments from adopting minimum wage ordinances and rent control laws.

And the list grows every year. After all, why expect a state legislature not to use a power that allows them to provide special treatment to the largest corporations in their state?

Public Resources for Private Gain

It used to be enough for the state to use its lawmaking power to preempt municipal laws and to let corporations do the rest. However, at some point corporate decisionmakers questioned why their own resources were being expended to enforce what the state had adopted. After all, if the state legislature felt strongly enough to preempt, why shouldn’t the state itself take some responsibility to enforce it?

In other words, the use of public lawmaking processes to shield corporate actors wasn’t sufficient anymore, especially as more and more communities feeling the brunt of harmful corporate projects began to pass more and more local laws to stop those projects.

From the vantage point of corporations, now was the time to use public resources to enforce state preemption.

The New York Experience: Protecting Agribusiness Operations

First, there was New York.

In the late 1980’s, in an effort to save disappearing farmland within the state, legislators adopted a provision within the State’s “Agriculture and Markets Law” (AML). The provision authorized county governments to establish agricultural districts in which farming was a protected use. The law then prohibited any local governments from enacting and enforcing local ordinances or regulations that “unreasonably restrict or regulate farm operations.” The definition of “farm operation” included all operations that “contribute to the production, preparation, and marketing of crops, livestock, and livestock products as a commercial enterprise.”

In other words, basically any activity involving crops or livestock was protected by the law, including large-scale hog and chicken confinement operations.

Pursuant to the law, the New York State Department of Agriculture and Markets – a state agency – was empowered to review any local enactments and determine whether they violated state law. If a municipality refused to repeal an ordinance found to be preempted, the Commissioner of the Department – using public, taxpayer resources – was authorized to file suit directly against the municipality in the New York State Supreme Court.

While the law has been used in a litany of cases to strike down protective zoning ordinances, it has been the threat of facing off against a state lawsuit that is usually enough to force municipal officials to repeal their laws.

The Pennsylvania Experience: New York on Steroids

Then, there was Pennsylvania.

In 2005, the legislature of the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania took a cue from New York’s experiment and enacted the Agriculture, Communities, and Rural Environment (“ACRE”) law. This was in response to a stream of confrontations between corporations seeking to site large hog and chicken confinement operations and the people of rural municipalities concerned about those facilities. ACRE authorized the state Attorney General to directly override any local laws that interfered with “normal agricultural operations.”

Like New York legislators, Pennsylvania legislators broadly defined the phrase as including “customary and generally accepted activities, practices, equipment, and procedures that farmers adopt, use or engage in.” As in New York, the definition embraced massive, agribusiness livestock operations, as well as any activity related to farming – such as the dumping of sewage sludge onto farmland.

The law gave the State Attorney General, acting with public, taxpayer monies, the authority to review municipal ordinances and to file suit – in the name of the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania – against municipal governments.

And sue they have.

The law has been used to strike down setbacks for chicken factory farms, timber harvesting restrictions, bans and limits on hog confinement facilities, odor ordinances, restrictions on mushroom production, restrictions on large-scale water withdrawals, and the use of sewage sludge for crop production. Since its adoption in 2006, close to fifty municipal laws have been scrutinized by the Attorney General’s office. Most of those laws were repealed or changed by municipal officials or overturned by a court following a lawsuit brought by the state.

Colorado: A Democratic Governor Protects Oil and Gas Drilling

On July 12, 2012, Governor John Hickenlooper took preemption to new heights when he authorized the Colorado Oil and Gas Conservation Commission to sue the City of Longmont to overturn Longmont’s ban on fracking within the City’s residential areas. The State Commission, tasked with regulation of oil and gas extraction in the state, declared that the City’s oil and gas rules “trespassed” into areas meant to be “governed by the state.”

The Governor’s action came on the heels of new laws adopted by several Colorado municipalities seeking to regulate and ban fracking for natural gas within their communities. Those municipalities included the City of Lafayette. Residents overwhelmingly adopted a citizen’s initiative that banned oil and gas extraction within the municipality as a violation of the rights of residents to clean air and clean water.

The state’s preemption law makes oil and gas extraction the exclusive domain of the state. The Colorado Supreme Court issued a ruling on May 1, 2016 reaffirming state preemption over extraction. The court overturned Longmont’s ban. That ruling is now routinely used by the Colorado Oil and Gas Conservation Commission, and the private Colorado Oil and Gas Association, to threaten elected officials who propose the adoption of any new regulations for oil and gas drilling within their municipalities.

Don’t Mess with Texas: Vindicating State Preemption Over Oil and Gas Drilling

Not to be outdone by their Democratic counterparts in Colorado, on November 4, 2014, the State of Texas’ General Land Office joined with the Texas Oil and Gas Association to sue Denton. Less than 24 hours prior, Denton residents had overwhelmingly approved a ban on hydraulic fracturing within their City. Their claim in the lawsuit? That the ban on fracking violated Texas’ preemption law on oil and gas drilling, which prohibits cities from passing any local ordinances that conflict with state law.

As declared by the lawsuit, “by imposing a complete ban on hydraulic fracturing on oil and gas leases within its city limits, the city of Denton undermines this comprehensive state system of regulating oil and gas development. . .The ordinance’s complete ban second-guesses and impedes this state regulatory framework.”

Legislators in the State House and Senate were alarmed by the adoption of the ordinance by the residents of Denton. They went to work to strengthen existing preemption laws. The result was House Bill 40, which established blanket, explicit preemption over any activity “related” to oil and gas drilling in the state.

Governor Abbott signed the bill on May 18, 2015, and on June 15th – faced with pending lawsuits and the new state law – the Denton City Council voted 6-1 to repeal its ordinance, declaring that a repeal was “in the best interests of Denton taxpayers.”

Lesson? Don’t mess with Texas.

Emboldened Legislators

Recently, legislators have gotten even bolder. Texas mayors who oppose a statewide ban on sanctuary cities risk a $25,000 per day civil fine. In Arizona, the state can now punish municipalities by withholding sales tax revenues from them if they adopt local laws that are preempted.

Preemption laws are also on the rise – in a study released this week by the National League of Cities, “City Rights in an Era of Preemption,” the League identified 19 new state preemptive laws passed in the last year that prohibit the adoption of municipal laws on paid leave, anti-discrimination, and municipal broadband.

Why is Preemption Legal?

While Florida firearm preemption laws are severe in terms of punishment, the state legislature merely had to follow the footsteps of those who came before them, and then up the ante.

Like the proverbial fox guarding the henhouse, state legislators are the ones who decide how much power they, themselves, should be able to wield. When pressured by large economic actors in their state – whether that be agribusiness interests, waste management corporations, or the gun lobby – preemption provides a convenient way of passing out favors. Those favors now include not only the adoption of laws that shield those key supporters, but also the use of state resources to directly enforce those laws.

Given that far-reaching power, it’s strange how silent activist lawyers and organizations have been over challenging preemption directly. It is treated as a “well-settled” doctrine with the status of a sacred cow. Rarely does any municipality even entertain the thought that the state is acting unconstitutionally or illegally when it exercises its power to preempt.

That’s mostly because preemption has been around for so long that it boasts the appearance of being an inevitable part of a democratic system. By its very nature, however, it is one of the most anti-democratic tools of them all. No wonder it’s the corporate establishment’s weapon of choice.

The Fabrication of Preemption: John Forrest Dillon

Its creation stems from a legal doctrine known as “Dillon’s Rule.” Named after John Forrest Dillon, a railroad attorney who then became the Chief Justice of the Iowa Supreme Court, Dillon established the relationship of the state to a municipality as one of a “parent to a child,” with the child only having the powers that the state legislature says they have. Dillon’s Rule was eventually embraced by the United States Supreme Court in Hunter v. City of Pittsburgh, in which the Court declared that:

Municipal corporations owe their origin to, and derive their powers and rights wholly from, the legislature. It breathes into them the breath of life, without which they cannot exist. As it creates, so may it destroy. If it may destroy, it may abridge and control…Local governments are, so to phrase it, the mere tenants at will of the legislature.

It’s why state governments can annex, alter, and even abolish municipalities at will. Indeed, as Dillon himself once wrote, it’s not even necessary that people living in cities, towns, villages, and counties elect municipal representatives; as a “creation” of the state, the municipality exists merely to administer state law, a function that can be legally attained with state appointees, rather than with elected officials.

Preemption as a doctrine thus flows naturally from Dillon’s Rule. As the parent, state legislatures can define and re-define – at will – what legislative authority municipalities possess. They can narrow, abolish, remove, and punish renegade municipal governments that act outside of their state-defined authority.

Our municipal governments are thus serfs living on property owned by someone else. Within our own municipalities, we are accorded an even lesser status, and are often left holding the bag when our centralized state governments decide to give away the store.

Drawing the Line: A Constitutional Right to Govern Ourselves

Many people who are familiar with the “whack-a-mole” routinely visited on cities, towns, villages, townships, and counties by their own state governments, have decided to fight back. Known as the “Community Rights movement,” these municipalities, activists, and lawyers are charging that the doctrine of preemption itself – when exercised to nullify local laws that seek to impose stricter standards for the protection of people and the environment – is unconstitutional. They assert that the doctrine is unconstitutional because it violates the constitutional right of the residents of those municipalities to local community self-government.

They see the movement as a necessary bulwark against preemptive power run amuck; and a necessary limiter to state legislators who always seem to come down on the side of large corporations against the municipalities that those legislators ostensibly represent.

It doesn’t take new math to understand how a constitutional right of local self-government would affect the doctrine of preemption.

If the state government lacks the authority to preempt certain types of municipal legislation, then the state government lacks the power to directly enforce those preemptive laws. If the state government lacks the authority to enforce those laws, then the state government lacks the authority to punish elected officials for running afoul of them.

Falling Short

Which brings us back to those ten Florida cities who filed suit last week against the state of Florida. While the lawsuit is the courageous act of local officials on the receiving end of the punishments contained within the state law, it falls short of directly challenging the doctrine of preemption itself. Instead, it seeks a ruling that the legislature exceeded its boundaries in giving the Governor the power to remove elected officials, and that the legislature violated the doctrine of immunity from suit for elected officials operating in their official capacity.

Even a wholesale victory in the case would not remove the preemptive state law from effect, or define the boundaries of authority under which the legislature has adopted that law. It also would not stop the state from providing its own agents and resources to enforce the law, and it would not stop any private litigants, like the NRA, from suing municipal governments to enforce the law.

In short, while removing the most severe repercussions of the law, it fails to target the bedrock power that allowed the adoption of the law in the first place.

No one can blame the local officials for aiming so low; after all, courts have embraced the doctrine of preemption like no other over the past hundred years. But until we begin aiming higher and recognize that preemption is a fast road to nowhere, we will be left on the receiving end of a power whose limits are self-defined by those who seek to benefit from it.

The Community Environmental Legal Defense Fund is partnering with communities across the country to challenge state preemption through advancing Community Rights. We provide grassroots organizing, education and outreach, and legal support to help communities realize their right to local community self-government and their right to enact protections greater than those provided by state and federal government. Our work is possible with your support. Please donate today!