Communities across the country face preemption by their own state and federal governments as they fight to protect themselves from environmental harms, religious persecution, gender and sexual orientation discrimination, and economic exploitation. Communities adopt laws to advance rights and protect their health, safety, and welfare, through their local representatives or through citizen initiative. In response, state and federal governments are nullifying their laws, blocking them from the ballot, or punishing them for daring to govern themselves.

Our courts interpret state and federal law to supersede local laws – even when local laws provide greater protections for people’s rights. This exclusive preemption doctrine prevents local governments from advancing people’s rights, and protecting health, safety, and welfare. We, the people, must drive the courts to recognize that preemption cannot be used as a ceiling on local government’s advancement of rights and protection for people.

Our courts interpret state and federal law to supersede local laws – even when local laws provide greater protections for people's rights.

The problem: ceiling preemption is a weapon, not a neutral principle in federalism

With “ceiling preemption,” state or federal law sets the maximum level of protection for people’s rights, health, safety, and welfare. In contrast, with “floor preemption,” state or federal law provides a minimum level of protection (above which local law can provide greater protections).

Communities across the U.S. have firsthand experience of ceiling preemption as a problem. They live it daily as they are prevented from enacting or enforcing laws that safeguard rights and protections.

Backing them up, local government scholar Richard Briffault describes some of the policy problems with ceiling preemption, namely how it thwarts home rule, policy innovation, decentralization, and local democracy:

If a state standard-setting or regulatory law was considered to determine both the ceiling as well as the floor for regulation, there would be no space for local regulation once the state had acted. That would choke off home rule and frustrate the democratic, decentralizing, and innovative goals that animate it.1

As well, the National League of Cities has identified ceiling preemption as a problem. In a February 2017 study, the NLC found that many states use preemption as a ceiling on local governments’ advancing civil rights and local economic development.2

Using “floor preemption” for greater protection

Through most of the twentieth century, human rights advocates focused on expanding the protections provided by the United States Constitution’s Bill of Rights. But after the United States Supreme Court began turning away from civil rights and civil liberties protections in the late 1970’s (and thus narrowing the protections afforded by the federal constitution), human rights advocates began relying on state constitutional rights protections. 3

In the 1980’s and 1990’s, most state supreme courts recognized that state constitutions could provide greater protection for civil rights and civil liberties. In other words, the federal Bill of Rights did not preempt the state constitutions when the state law provided greater protection.4

The southern-facing main facade of the United States Supreme Court, overlooking Capitol Hill. Matt Popovich, Flickr Creative Commons

Equally important, the United States Supreme Court has applied the “floor preemption” versus “ceiling preemption” framework to state constitutional rights protections. For example, in Pruneyard Shopping Ctr. v. Robins, 447 U.S. 74 (1980), the court held that states can provide greater rights protections than the federal constitution. And in Romer v. Evans, 517 U.S. 620 (1996), the court held that a Colorado constitutional amendment that prevented protected status based on homosexuality violated the federal Equal Protection Clause.

Legal scholars describe this framework as the “new judicial federalism.” With this new judicial federalism, the federal constitution provides the “floor” – a person’s minimum rights – and state constitutions can go above that floor.

The solution: add local governments to the new judicial federalism

Thus, in American constitutional law today, there exists a framework for differentiating “ceiling preemption” from “floor preemption” – and prohibiting the former while enabling the latter. To address the issues of weaponized preemption, this framework can be expanded to protect local laws that go above the “floor” provided by state or federal law.

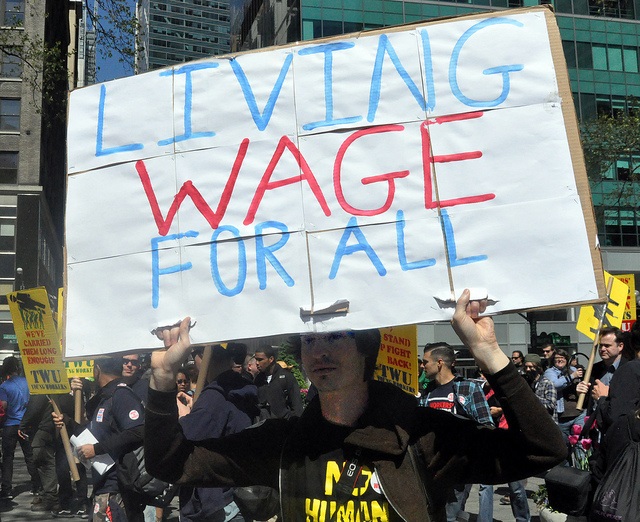

For example, the National League of Cities found that nearly half the states use ceiling preemption to prevent local governments from enacting higher minimum wage laws. This ceiling preemption prevents local governments from protecting people’s economic rights and welfare. The courts validate this practice with the exclusive preemption doctrine – allowing preemption to be both a ceiling and a floor, and invalidating local laws that expand protections.

mayday_NYC2013_DSC_0067 by Michael Fleshman, Flickr Creative Commons

If instead, communities drive the courts to recognize that state law can provide a floor, but not a ceiling, then local governments would be able to enact higher minimum wage laws (as well as paid sick leave laws, etc.) to protect people’s economic rights and welfare. The state would be unable to weaponize preemption as a tool to suppress local democracy, the benefits of decentralized policy, and the innovative potential of policy experimentation.

Making it happen

Past people’s movements have taught us that the courts change only when driven by the 99%. From abolition, to the Civil Rights era, to gay marriage rights – each of these movements achieved the advancement of rights through unrelenting, purposeful action by we, the people.

Today, across the U.S., communities are insisting on their right to protect themselves and advance rights – regardless of state ceiling preemption. Through their relentless drive to govern the places where they live, they will also drive the courts to recognize that rights, health, safety, and welfare cannot be limited by the state.

The framework is here: American constitutional law already differentiates between ceiling preemption and floor preemption when considering rights protections provided by state constitutions. To ensure that state and federal governments do not use state or federal law to suppress rights protections, communities must force the courts to prohibit ceiling preemption, and recognize the authority of local governments to advance rights and protect people’s health, safety, and welfare.

CELDF assists communities across the U.S. to advance their right to local community self-government, whereby the state and federal government set the “floor,” or minimum rights protections, and communities have the right to create and enforce broader rights protections. Our work to advance local self-governing rights is made possible by your donations. Please support democratic rights today!

1 Richard Briffault, Home Rule for the Twenty-First Century, 36 URBAN L AWYER 253, 264-65 (2004)

2 National League of Cities, City Rights in an Era of Preemption: A State-by-State Analysis (Feb. 22, 2017), available at http://nlc.org/preemption

3 See William J. Brennan, Jr., State Constitutions and the Protection of Individual Rights, 90 HARV. L. REV. 489 (1977)

4 See, e.g., Stephen Kanter, Sleeping Beauty Wide Awake: State Constitutions as Important Independent Sources of Individual Rights, 15 LEWIS & CLARK L. REV. 799 (2011)