What is it that keeps us from getting what we want in our communities? Why can’t we say, “No!” to harmful activities?

The short answer is: THE LAW. A handful of legal doctrines make it illegal for communities to govern on important issues like fracking, factory farms, large-scale energy infrastructure projects and commercial water extraction. Many people work hard to create sustainable communities, but these legal doctrines keep us “boxed in” by a system of law that routinely restricts local law-making and tells us that “We’re beyond our authority,” or “It’s a state issue, not a local issue.”

We’ll use the issue of fracking (although you can insert almost any issue that your community is concerned about) to illustrate how these legal doctrines preempt our decision-making, legalize the harms that come from fracking, and protect the industry from citizen opposition.

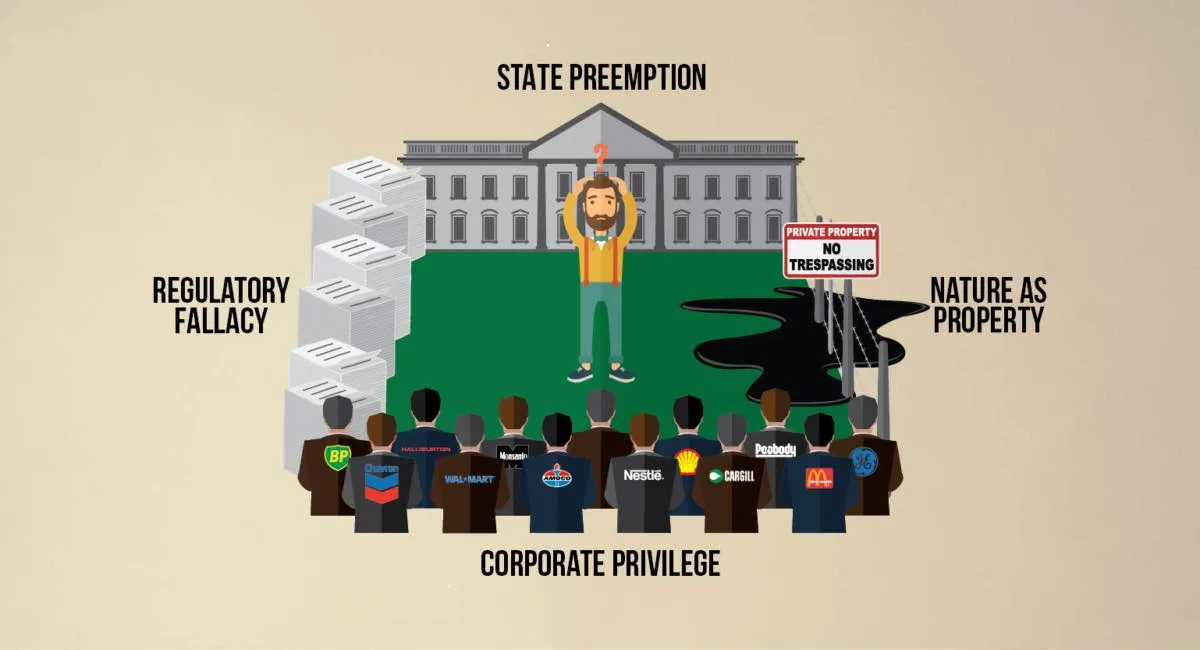

Looking at the diagram above, you’ll notice the doctrines of “State Preemption” and “Dillon’s Rule.” Preemption means the state legislature enacts law that removes authority from the community to govern on a particular issue.

Dillon’s Rule compliments state preemption by defining the legal relationship between the state and the municipality as that of a parent to a child. In the case of fracking, the (abusive)parental state has slapped the municipal child’s hand and told them not to touch decisions about fracking. In doing this, the people living within the municipality are deprived of the right to protect their own rights.

Looking at the legal doctrine of “Nature as Property” on the right side of the diagram, we see that nature is considered property under the law. Anyone with a title to property has the legal right to destroy it. With a permit from the state, the harms to ecosystems and the community members who rely on those ecosystems are legalized. Nature and human beings who do not have a title to the land, or a financial interest in that land, lack legal standing to argue in court to protect the ecosystem. With fracking, title of ownership – or a lease with a drilling company – trumps the health, safety, and welfare of the community and the viability of the ecosystem. It’s the same for GMO’s, water mining, sludge dumping, etc.

At the bottom of the diagram is Corporate Privilege. Often referred to as corporate “rights,” or “personhood,” it means that corporations claim “rights” to protections of free speech (1st amendment/money as speech), protections from search and seizure (4th amendment), due process and lost future profits (5th amendment Takings clause) and equal protection (14th amendment). Contracts clause protections, civil rights laws, and commerce laws, further amplify corporate power to override local decision-making.

The fourth legal doctrine on the left side of the diagram above, entitled the “Regulatory Fallacy,” suggests there is a way out of the Box. The permitting process, and the regulations supposedly enforced by regulatory agencies, are intended to create a sense of protection and objective oversight. By working through regulatory agencies such as the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and our state agencies, we’re told we can protect our community. We can challenge permit applications and demand regulations be enforced. Except, by their very definition, regulatory agencies regulate the amount of harm that takes place. When they issue permits, they give cover to the applicant against liability to the community for the legalized harm.

We’re encouraged to come to the hearing at 7 pm Thursday evening if we’re opposed to fracking. No one bothers to tell us that no matter how harmful fracking is, municipalities cannot ban anything permitted by the state (see State Preemption at the top of the diagram). We present our three minute, impassioned oration about the risk to community health – but in the end, nothing we say must be taken into account by the agency in the decision to issue the permit. If the application is clerically in order and complete, the permit is given. The harms are legalized. The permitting agency is in business to facilitate the issuance of the permit, not to protect people or the ecosystem. The idea that regulations protect us is a fallacy; by their very definition, they permit harm and we’re taught that our best option is to regulate just how much of it we are required to accept.

You might argue: But zoning let’s us stop harms, right? Well, not really. Zoning allows us, in most cases, to decide where industrial damage can occur. In other words, we get to choose which part of our community we want sacrificed to the harmful corporate activity.

While our legal system creates the illusion that we have a democracy, State Preemption and Dillon’s Rule, Nature as Property, Corporate “Rights,” and the Regulatory Fallacy all funnel us into a trap where we’re told, when it comes to actual governing and creating sustainable communities, “We’re beyond our authority.”

The final blockade to community self-government is the Black Hole of Doubt. We think we’re not smart enough, strong enough, or empowered enough – we literally do not believe we have the inalienable right to govern. Sally Kempton, author and feminist, says, “It’s hard to defeat an enemy who has outposts in your head.”

In a Democratic nation, self-government should not be a foreign idea. We are the ones we’ve been waiting for.

What is it that keeps us from getting what we want in our communities? Why can’t we say, “No!” to harmful activities?

The short answer is: THE LAW. A handful of legal doctrines make it illegal for communities to govern on important issues like fracking, factory farms, large-scale energy infrastructure projects and commercial water extraction. Many people work hard to create sustainable communities, but these legal doctrines keep us “boxed in” by a system of law that routinely restricts local law-making and tells us that “We’re beyond our authority,” or “It’s a state issue, not a local issue.”

We’ll use the issue of fracking (although you can insert almost any issue that your community is concerned about) to illustrate how these legal doctrines preempt our decision-making, legalize the harms that come from fracking, and protect the industry from citizen opposition.

Looking at the diagram above, you’ll notice the doctrines of “State Preemption” and “Dillon’s Rule.” Preemption means the state legislature enacts law that removes authority from the community to govern on a particular issue.

Dillon’s Rule compliments state preemption by defining the legal relationship between the state and the municipality as that of a parent to a child. In the case of fracking, the (abusive)parental state has slapped the municipal child’s hand and told them not to touch decisions about fracking. In doing this, the people living within the municipality are deprived of the right to protect their own rights.

Looking at the legal doctrine of “Nature as Property” on the right side of the diagram, we see that nature is considered property under the law. Anyone with a title to property has the legal right to destroy it. With a permit from the state, the harms to ecosystems and the community members who rely on those ecosystems are legalized. Nature and human beings who do not have a title to the land, or a financial interest in that land, lack legal standing to argue in court to protect the ecosystem. With fracking, title of ownership – or a lease with a drilling company – trumps the health, safety, and welfare of the community and the viability of the ecosystem. It’s the same for GMO’s, water mining, sludge dumping, etc.

At the bottom of the diagram is Corporate Privilege. Often referred to as corporate “rights,” or “personhood,” it means that corporations claim “rights” to protections of free speech (1st amendment/money as speech), protections from search and seizure (4th amendment), due process and lost future profits (5th amendment Takings clause) and equal protection (14th amendment). Contracts clause protections, civil rights laws, and commerce laws, further amplify corporate power to override local decision-making.

The fourth legal doctrine on the left side of the diagram above, entitled the “Regulatory Fallacy,” suggests there is a way out of the Box. The permitting process, and the regulations supposedly enforced by regulatory agencies, are intended to create a sense of protection and objective oversight. By working through regulatory agencies such as the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and our state agencies, we’re told we can protect our community. We can challenge permit applications and demand regulations be enforced. Except, by their very definition, regulatory agencies regulate the amount of harm that takes place. When they issue permits, they give cover to the applicant against liability to the community for the legalized harm.

We’re encouraged to come to the hearing at 7 pm Thursday evening if we’re opposed to fracking. No one bothers to tell us that no matter how harmful fracking is, municipalities cannot ban anything permitted by the state (see State Preemption at the top of the diagram). We present our three minute, impassioned oration about the risk to community health – but in the end, nothing we say must be taken into account by the agency in the decision to issue the permit. If the application is clerically in order and complete, the permit is given. The harms are legalized. The permitting agency is in business to facilitate the issuance of the permit, not to protect people or the ecosystem. The idea that regulations protect us is a fallacy; by their very definition, they permit harm and we’re taught that our best option is to regulate just how much of it we are required to accept.

You might argue: But zoning let’s us stop harms, right? Well, not really. Zoning allows us, in most cases, to decide where industrial damage can occur. In other words, we get to choose which part of our community we want sacrificed to the harmful corporate activity.

While our legal system creates the illusion that we have a democracy, State Preemption and Dillon’s Rule, Nature as Property, Corporate “Rights,” and the Regulatory Fallacy all funnel us into a trap where we’re told, when it comes to actual governing and creating sustainable communities, “We’re beyond our authority.”

The final blockade to community self-government is the Black Hole of Doubt. We think we’re not smart enough, strong enough, or empowered enough – we literally do not believe we have the inalienable right to govern. Sally Kempton, author and feminist, says, “It’s hard to defeat an enemy who has outposts in your head.”

In a Democratic nation, self-government should not be a foreign idea. We are the ones we’ve been waiting for.

What is it that keeps us from getting what we want in our communities? Why can’t we say, “No!” to harmful activities?

The short answer is: THE LAW. A handful of legal doctrines make it illegal for communities to govern on important issues like fracking, factory farms, large-scale energy infrastructure projects and commercial water extraction. Many people work hard to create sustainable communities, but these legal doctrines keep us “boxed in” by a system of law that routinely restricts local law-making and tells us that “We’re beyond our authority,” or “It’s a state issue, not a local issue.”

We’ll use the issue of fracking (although you can insert almost any issue that your community is concerned about) to illustrate how these legal doctrines preempt our decision-making, legalize the harms that come from fracking, and protect the industry from citizen opposition.

Looking at the diagram above, you’ll notice the doctrines of “State Preemption” and “Dillon’s Rule.” Preemption means the state legislature enacts law that removes authority from the community to govern on a particular issue.

Dillon’s Rule compliments state preemption by defining the legal relationship between the state and the municipality as that of a parent to a child. In the case of fracking, the (abusive)parental state has slapped the municipal child’s hand and told them not to touch decisions about fracking. In doing this, the people living within the municipality are deprived of the right to protect their own rights.

Looking at the legal doctrine of “Nature as Property” on the right side of the diagram, we see that nature is considered property under the law. Anyone with a title to property has the legal right to destroy it. With a permit from the state, the harms to ecosystems and the community members who rely on those ecosystems are legalized. Nature and human beings who do not have a title to the land, or a financial interest in that land, lack legal standing to argue in court to protect the ecosystem. With fracking, title of ownership – or a lease with a drilling company – trumps the health, safety, and welfare of the community and the viability of the ecosystem. It’s the same for GMO’s, water mining, sludge dumping, etc.

At the bottom of the diagram is Corporate Privilege. Often referred to as corporate “rights,” or “personhood,” it means that corporations claim “rights” to protections of free speech (1st amendment/money as speech), protections from search and seizure (4th amendment), due process and lost future profits (5th amendment Takings clause) and equal protection (14th amendment). Contracts clause protections, civil rights laws, and commerce laws, further amplify corporate power to override local decision-making.

The fourth legal doctrine on the left side of the diagram above, entitled the “Regulatory Fallacy,” suggests there is a way out of the Box. The permitting process, and the regulations supposedly enforced by regulatory agencies, are intended to create a sense of protection and objective oversight. By working through regulatory agencies such as the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and our state agencies, we’re told we can protect our community. We can challenge permit applications and demand regulations be enforced. Except, by their very definition, regulatory agencies regulate the amount of harm that takes place. When they issue permits, they give cover to the applicant against liability to the community for the legalized harm.

We’re encouraged to come to the hearing at 7 pm Thursday evening if we’re opposed to fracking. No one bothers to tell us that no matter how harmful fracking is, municipalities cannot ban anything permitted by the state (see State Preemption at the top of the diagram). We present our three minute, impassioned oration about the risk to community health – but in the end, nothing we say must be taken into account by the agency in the decision to issue the permit. If the application is clerically in order and complete, the permit is given. The harms are legalized. The permitting agency is in business to facilitate the issuance of the permit, not to protect people or the ecosystem. The idea that regulations protect us is a fallacy; by their very definition, they permit harm and we’re taught that our best option is to regulate just how much of it we are required to accept.

You might argue: But zoning let’s us stop harms, right? Well, not really. Zoning allows us, in most cases, to decide where industrial damage can occur. In other words, we get to choose which part of our community we want sacrificed to the harmful corporate activity.

While our legal system creates the illusion that we have a democracy, State Preemption and Dillon’s Rule, Nature as Property, Corporate “Rights,” and the Regulatory Fallacy all funnel us into a trap where we’re told, when it comes to actual governing and creating sustainable communities, “We’re beyond our authority.”

The final blockade to community self-government is the Black Hole of Doubt. We think we’re not smart enough, strong enough, or empowered enough – we literally do not believe we have the inalienable right to govern. Sally Kempton, author and feminist, says, “It’s hard to defeat an enemy who has outposts in your head.”

In a Democratic nation, self-government should not be a foreign idea. We are the ones we’ve been waiting for.