Feature photo by Samuel Regan-Asante on Unsplash

Opposing harmful industrial projects – like mines, aerial pesticide spraying, factory farms, or toxic waste disposal facilities – is scary and difficult work. Feeling this fear and confronting the difficulty of the work, it is tempting to cling to false, but comforting beliefs that the communities we belong to possess more rights to protect us than they actually do.

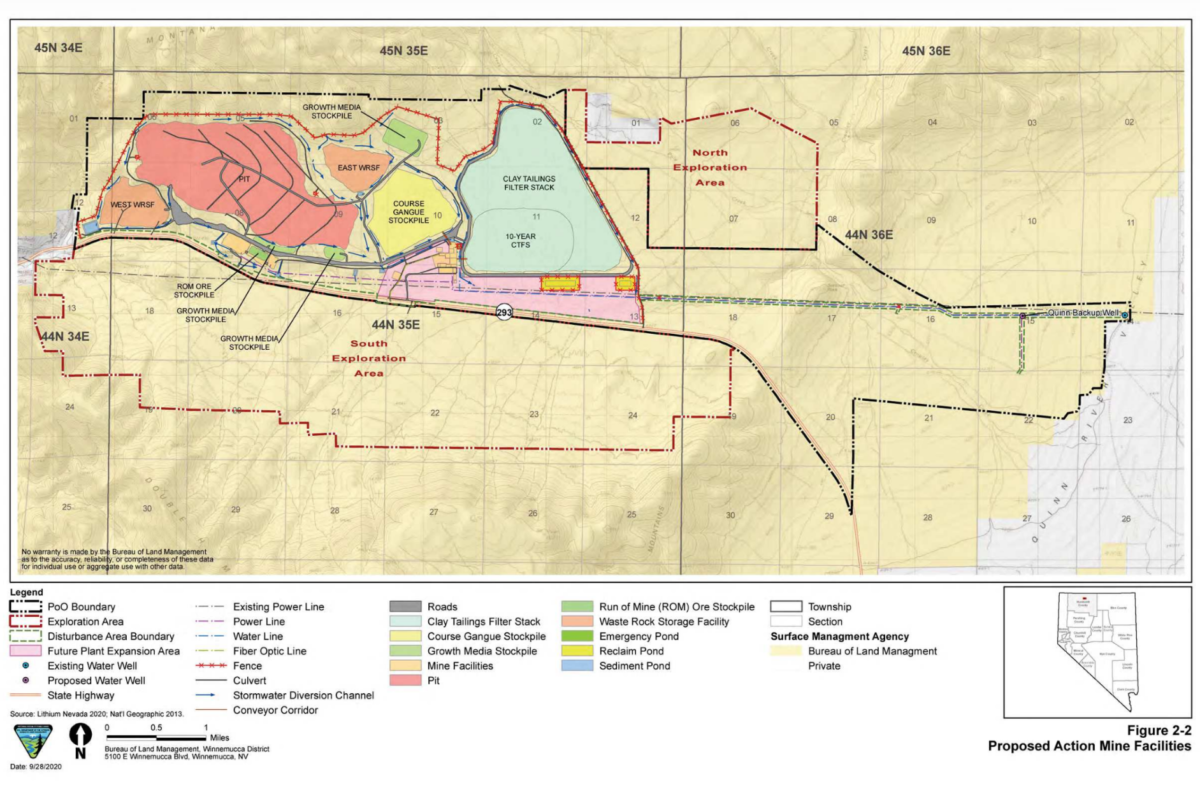

I am a grassroots community organizer and lawyer. I am not Native but I have worked in both Native and non-Native American communities opposing industrial harms that threaten them. For the past three and a half years, I’ve been involved in a campaign to stop a massive open pit lithium mine from destroying sites sacred to Paiute and Shoshone people at Thacker Pass in Northern Nevada. On January 15, 2021, the same day the federal government issued the last major permit for Lithium Nevada Corporation’s Thacker Pass Lithium Mine Project, along with my colleague Max Wilbert, I co-founded Protect Thacker Pass and set up a protest camp where the project’s proposed open pit mine would be constructed. I spent most of 2021 living in a tent and protesting the mine. When it became clear that no one was representing Native American interests in legal actions against the mine, I began representing two tribes against the federal government for permitting the mine. In late 2021, Max and I were fined nearly $50,000 for constructing temporary composting outhouses – at the request of local tribal elders who needed a place to use the bathroom while engaging in ceremony at the site – on the same land that would be destroyed for the mine’s 1,100 acre open pit. In June 2023, I was sued along with Native and other water and land protectors, for peacefully protesting at the Thacker Pass mine site after legal challenges to the project failed.

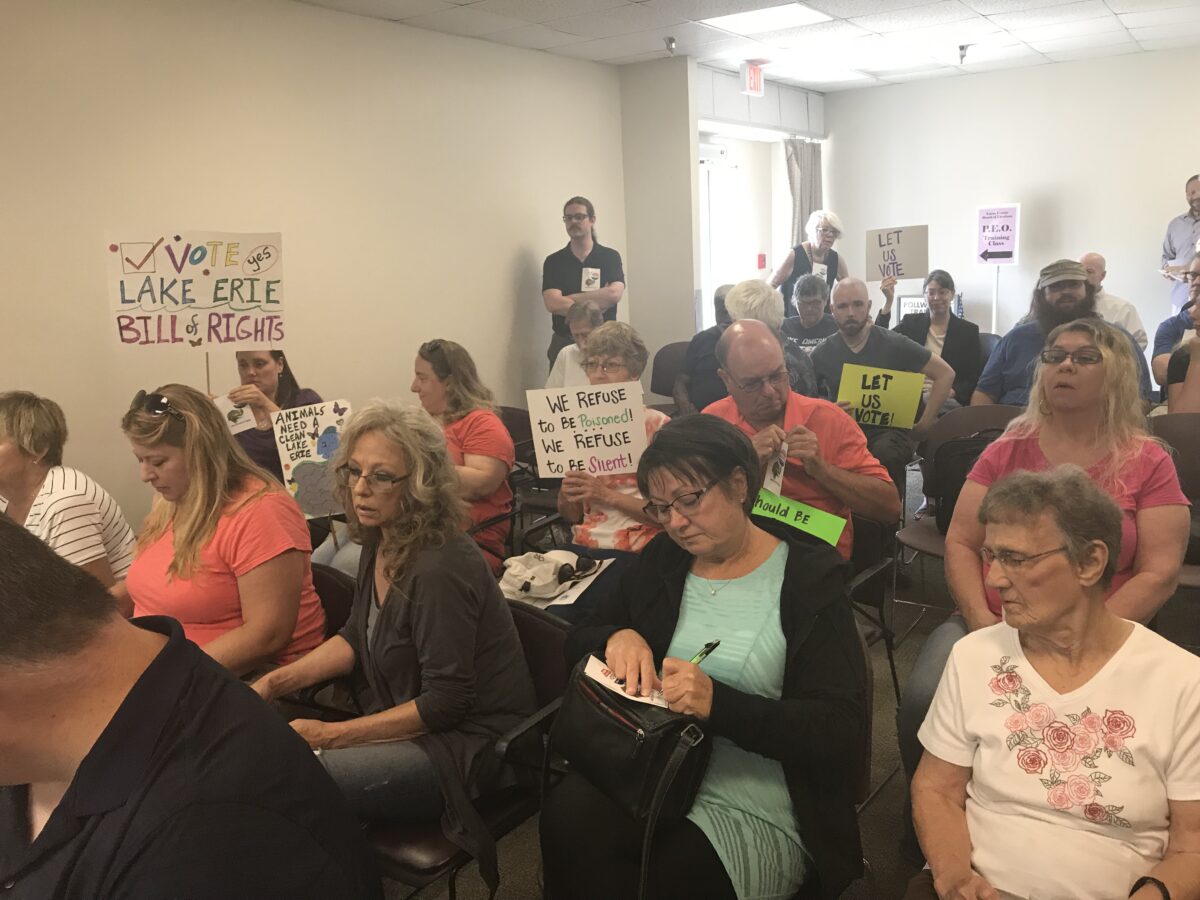

I also work with the Community Environmental Legal Defense Fund (CELDF) and have been involved in campaigns in non-Native communities to help those communities assert their right to local self-government and the rights of nature. With CELDF, I assisted the citizens of Toledo, OH to enact the Lake Erie Bill of Rights, which gave Lake Erie the rights to exist, flourish, and naturally evolve; gave the people of the City of Toledo the right to self-government in their local community; and which stripped corporations of any rights that interfered with Lake Erie’s rights or Toledo citizens’ right to local self-government. I helped Toledo residents attempt to intervene in a federal lawsuit to defend the Lake Erie Bill of Rights from corporate attack where it was ultimately struck down for exceeding municipal authority and infringing upon corporate rights.

A comforting but false belief I often encounter that diverts communities from effectively protecting themselves from social and environmental harm is the belief that American law gives communities a say over whether the government will allow destructive industrial projects to be constructed in their communities. Many Americans envision processes like public hearings and comment periods as fundamentally democratic. They believe that if enough residents tell the government they do not want an industrial project in their community the government will listen and refuse to issue permits for the project. After all, we are taught “we live in a democracy, of, by and for the people.”

This belief of community input making a difference in outcomes is widespread in both Native and non-Native American communities. With the government parroting terms like “tribal sovereignty” and “government-to-government consultation,” many people assume that Native Americans really do have sovereignty over their lands. Similarly, with many state constitutions declaring that communities have a right to local self-government, many Americans believe that their communities really do possess a right to local self-government.

Unfortunately, federally-recognized tribes in the United States are not actually sovereign nations and American communities do not actually possess a meaningful right to local self-government.

Many Native Americans understand that the United States has colonized them, while many non-Native Americans do not recognize that they have also been colonized. This is not to say that all forms of colonization are the same. Non-Native American settlers benefit from a colonial system that is built on land and labor stolen from Native Americans. Many municipalities have been involved in stealing this land and pushing Native Americans away from municipalities. However, social and environmental justice movements in the United States would benefit from recognizing the similar ways in which American law disempowers both Native and non-Native American communities. When Native and non-Native Americans recognize the similar way in which they’ve been disempowered, they can realize the common cause they both share, combine their strengths, and work more effectively to claim true sovereignty.

White Man’s Reservation

More non-Native Americans need to recognize the way they’ve been colonized. My colleague at CELDF, Ben Price, offers a story that illustrates this in a blog post he wrote in 2020 to honor the passing of Lakota activist Debra White Plume (Wioweya Najin Win). Debra was a brave advocate for her people and memorialized by the New York Times as a “prominent Native American activist who faced down police bullets, uranium mining companies and oil pipeline projects in trying to protect the traditional Oglala Lakota way of life.”

Ben was invited by the Chadron Native American Center just south of the Pine Ridge Reservation to teach a class about the evolution of corporate power in the United States. After Ben explained how municipalities under American law are not given the power to ban corporate projects within city limits, Debra stood up and said something Ben will never forget. “‘Hmmm,’ she said, ‘so municipalities are the white man’s reservations. The only difference is, we know we’re on reservations.’”

Ben explained why Debra’s words were so important: “I could imagine no explanation of how commoners in the United States have been politically, economically, and legally subordinated to the corporate class. Only Americans choose to ignore this structure…Debra revealed a simple truth that stares non-Native Americans in the face, but too-often goes unnoticed.”

Tribal Sovereignty

The Cambridge Dictionary defines “sovereignty” as “the power of a country to control its own government.” The Merriam-Webster Dictionary includes in its definition “freedom from external control.” To assess whether tribes are actually sovereign in the United States, we need to ask: Do tribes possess the power to control their own government? Are they free from external control?

Rhetoric is not reality

The American government often makes proclamations that make it appear that the American government respects tribal sovereignty. In 2000, for example, the Clinton Administration issued an executive order titled “Consultation and Coordination with Indian Tribal Governments.” The order contains these exciting declarations:

“The United States recognizes the right of Indian tribes to self-government and supports tribal sovereignty and self-determination.” And, “Agencies shall respect Indian tribal self-government and sovereignty, honor tribal treaty and other rights, and strive to meet the responsibilities that arise from the unique legal relationship between the Federal Government and Indian tribal governments.”

A few days after taking office in January, 2021, Joe Biden issued a “Memorandum for the Heads of Executive Departments and Agencies” on “Tribal Consultation and Strengthening Nation-to-Nation Relationships” in which he expressed support for Clinton’s executive order quoted from above. In his memorandum, Biden declared: “It is a priority for my Administration to make respect for Tribal sovereignty and self-governance, commitment to fulfilling Federal trust and treaty responsibilities to Tribal Nations, and regular, meaningful, and robust consultation with Tribal Nations cornerstones of Federal Indian Policy.” More recently, on December 6, 2023, Biden issued an executive order on “Reforming Federal Funding and Support for Tribal Nations to Better Embrace Our Trust Responsibilities and Promote the Next Era of Tribal Self-Determination.” In the order, Biden declared, “My Administration is committed to protecting and supporting Tribal sovereignty and self-determination, and to honoring our trust and treaty obligations to Tribal Nations.”

This all sounds good, doesn’t it? The problem is, sounding good is all these proclamations do. They make people think that the federal government honors tribal sovereignty when in reality it does not.

I describe below how Congress and the courts make Biden’s declarations to support tribal sovereignty impossible. It might be tempting to conclude that members of the executive branch, here, are trying to do the right thing while Congress and the courts won’t let them. However, readers must remember that both Bill Clinton and Joe Biden are lawyers and Biden a former member of Congress and Clinton a former Governor. Both were or are supported by very capable lawyers who understand how tribal sovereignty really operates in this country. Biden’s statements are nothing more than political rhetoric designed to secure Native and sympathetic liberal votes. There will be no true tribal sovereignty until more people refuse to be pacified by these pretty sounding words.

Congress has declared that tribal nations are not independent nations

Under the American federal system of governance, the President does not make law. Congress makes law and federal courts interpret that law. In simpler terms: Congress writes the law and courts tell us what Congress wrote means.

Congress long ago clearly legislated that Indian tribes are not sovereign nations. On March 3, 1871, Congress passed Title 25, United States Code § 71, titled “Future treaties with Indian tribes” and declared: “No Indian nation or tribe within the territory of the United States shall be acknowledged or recognized as an independent nation, tribe, or power with whom the United States may contract by treaty…” Recall the definition of sovereignty given above. Sovereign nations are independent and have the power to make treaties with other sovereign nations. But, Congress explicitly declared in 1871 that no Indian nation or tribe is an independent nation with the power to make treaties with the United States.

Federal courts have declared that Congress has plenary power over the tribes

Federal courts have the final say over the rights possessed by federally recognized tribes. To assess what those rights are, it is necessary to examine court decisions about the rights of federally recognized tribes. Perhaps no one has described the situation as clearly as a Montana federal district court when the court explained: “No doubt the Indian

tribes were at one time sovereign and even now the tribes are sometimes described as being sovereign. The blunt fact, however, is that an Indian tribe is sovereign to the extent that the United States permits it to be sovereign – neither more nor less.” United States v. Blackfeet Tribe of Blackfeet Ind. Res., 364 F. Supp. 192, 194 (D. Mont. 1973).

The court is absolutely correct that “Indian tribes were at one time sovereign.” Before the arrival of Europeans in North America, each Native American First Nation was just that: a sovereign nation with the power to govern its own affairs, use militant force to defend its land and people, enter into treaties and agreements with other First Nations, etc. – all the powers that the truly sovereign nations of today possess. Beginning in 1492, European nations invaded North America. and Britain, France, Spain, the Netherlands, Russia and the United States systematically destroyed Native governments and the ability of Native nations to defend themselves. The result, today, is exactly as the Montana judge described: whatever so-called sovereignty Indian tribes now possess, that sovereignty only comes by the permission of the US government. This is not sovereignty, but the comforting illusion of sovereignty.

The Supreme Court is the supreme authority on the rights of federally-recognized tribes. The first Supreme Court case to explicitly address tribal sovereignty was Johnson and Graham’s Lessee v. William McIntosh, 21 US 543 (1823) (known colloquially as “Johnson v. McIntosh”). In Johnson v. McIntosh, Supreme Court Justice John Marshall formally adopted the Doctrine of Discovery, which holds that the first European nations to “discover” Native American lands gained the exclusive right to own those lands because those European nations were the first Christians to “discover” those lands.

The Supreme Court explained that the rights of Native Americans in land “discovered” by Europeans “were necessarily, to a considerable extent, impaired…their rights to complete sovereignty, as independent nations, were necessarily diminished…” Id. at 574. And, the European discovery of Native land gave the United States “an exclusive right to extinguish the Indian title of occupancy, either by purchase or conquest…” Id. at 587. Translation: the federal government has the legal right to push Native Americans off their land.

Sovereign nations have absolute and exclusive ownership over their lands. In Johnson v. McIntosh, Marshall explicitly rejected the notion that Indians have absolute and exclusive ownership over their lands: “All our institutions recognize the absolute title of the [federal government], subject only to the Indian right of occupancy, and recognize the absolute title of the [federal government] to extinguish that right. This is incompatible with an absolute and complete title in the Indians.” Id. at 588. In other words, the Supreme Court has never viewed tribes as being sovereign. This is true even for Supreme Court justices venerated by liberals like Ruth Bader Ginsburg who wrote in City of Sherrill v. Oneida Indian Nation of New York: “Under the Doctrine of Discovery…fee title to the land occupied by Indians when the colonists arrived became vested in the sovereign – first the discovering European nation and later the original States and the United States.” City of Sherrill v. Oneida Indian Nation of NY, 544 U.S. 197, 204, footnote 1 (2005)

Down to the 21st century, the Supreme Court has ruled that Congress’s power over Indian tribes is “plenary and exclusive.” United States v. Lara, 541 U.S. 193, 200 (2004). And, “It is thoroughly established that Congress has plenary authority over the Indians and all their tribal relations.” Winton v. Amos, 255 U.S. 373, 391 (1921). Plenary means full, complete, absolute, and unqualified. So, when the Supreme Court holds that Congress’s power over Indian tribes is “plenary,” that means Congress’s power over Indian tribes is full, complete, absolute, and unqualified. That doesn’t sound like sovereignty, does it?

A few more Supreme Court rulings about Congress’s plenary power of Indian tribes: “Our cases leave little doubt that Congress’s power [over Indian tribes] is muscular, superseding both tribal and state authority.” Brackeen v. Haaland, 599 U.S. ___ (2023). “Congress has plenary authority to limit, modify, or eliminate the powers of local self-government which the tribes otherwise possess.” Santa Clara Pueblo v. Martinez, 436 U.S. 49, 56 (1978). “Virtually all authority over Indian commerce and Indian tribes” lies with the federal government. Seminole Tribe of Fla. v. Florida, 517 U.S. 44, 62 (1996). “Congress possesse[s] a paramount power over the property of the Indians.” Lone Wolf v. Hitchcock, 187 U.S. 553, 565 (1903).

The enforceability of treaties between the federal government and Indian tribes is another widely misunderstood aspect of tribal non-sovereignty. Many people assume that treaties between the federal government and Indian tribes are imbued with some kind of magical force that binds the federal government to honor treaties made with Indian tribes. Unfortunately, that’s never been the case. The federal government, under American law, is not required to honor treaties made with Indian peoples. This should make readers angry. But, readers should resist the urge to deny this reality. Tribal sovereignty advocates who believe treaties will protect them will likely spend countless hours and money making treaty-based legal arguments that will not win.

I’ll quote the court decisions that state this below. However, we don’t really need to read those decisions to understand this. We just need to use common political sense and ask, when two truly sovereign nations enter into a treaty and one of those nations breaks the treaty, how does the sovereign nation who is harmed by the broken treaty enforce the treaty? The answer, of course, is simple: war. Or, at least, the credible threat of war. It is true that sovereign nations might try other things before war including economic sanctions, restrictive tariffs, withholding goods and services, threatening military intervention, diplomacy and compromise, etc.

But, at the end of the day, the only way to truly enforce a treaty is to physically force another nation to comply with the treaty. And, that happens at the point of a gun or the fat nose of a nuclear warhead. When was the last time an Indian tribe forced the United States to honor a treaty?

If that doesn’t convince you, let the Supreme Court:

“The power exists to abrogate the provisions of an Indian treaty…When, therefore, treaties were entered into between the United States and a tribe of Indians it was never doubted that the power to abrogate existed in Congress, and that in a contingency such power might be availed of from considerations of governmental policy…”

Lone Wolf v. Hitchcock, 187 US 553, 566 (1903).

Not only does Congress have the power to break treaties when it wants to, Congress has the power to terminate a tribe’s recognition. For example, on August 1, 1953, Congress passed House Concurrent Resolution No. 108, which became better known as the “Termination Act.” Between 1954 and 1964, Congress terminated 109 tribes in eight states. Today, if a tribe seeks federal recognition, it must petition the government and prove that it meets seven criteria that, according to the federal government, proves that the group seeking recognition is, in fact, a tribe. Again, if a nation is sovereign, that nation’s sovereignty cannot be revoked or terminated by another nation. And, if a nation is sovereign, that nation should not have to request that another nation recognize its sovereignty.

Regardless, despite rhetoric that makes people think tribes are sovereign, the truth is Congress has legislated that tribes are not independent nations, the Supreme Court has ruled over and over again that tribes are neither sovereign nor independent nations, that Congress has plenary power over Indian tribes, that Congress has power to break treaties with Indian tribes and even to terminate Indian tribes. This means that tribes do not control their own government nor are they free from external control. So, the tribes are not truly sovereign. And, while it is true that sometimes legal decisions beneficial to tribes are made, ultimate sovereignty over tribes lies with the federal government.

The Right to Local Self-Government

Many Americans assume that their communities have a right to ban activities that harm their communities. Let’s say, for example, that a corporation proposes to construct a fracking waste injection well within a small town’s city limits. The residents of that small town learn about the public health and environmental risks associated with these injection wells and, therefore, oppose the well’s construction. What legal options do these people have to stop the injection well?

If these citizens go to their city government and propose passing a law banning injection wells within city limits, the city attorney will introduce them to a legal doctrine known as “Dillon’s Rule,” which holds that a local government may exercise only those powers that their state government grants them. Or inform them of a state law passed by the legislature giving the state sole control and legal authority over oil/gas activities and preempting them from passing any laws on that topic.

Therefore, because these injection wells are legal under state and federal law, city laws banning injection wells are preempted and illegal.

John Forrest Dillon, the Iowa Supreme Court justice and later, general counsel to the Union Pacific Railroad and Western Union Telegraph Company, articulated “Dillon’s Rule,” describing the relationship between municipalities and state governments like this: “Municipal corporations owe their origin to, and derive their powers and rights wholly from, the legislature. It breathes into them the breath of life, without which they cannot exist. As it creates, so may it destroy. If it may destroy, it may abridge and control.” Clinton v Cedar Rapids and the Missouri River Railroad, (24 Iowa 455; 1868).

In 1907, the United States Supreme Court officially adopted Dillon’s Rule. The Court, referring to the powers of city governments, wrote:

“The State…at its pleasure may modify or withdraw all such powers, may take without compensation such property, hold it itself, or vest it in other agencies, expand or contract the territorial area, unite the whole or a part of it with another municipality, repeal the charter and destroy the corporation. All of this may be done, conditionally or unconditionally, with or without the consent of the citizens, or even against their protest. In all these respects, the State is supreme…” Hunter v. Pittsburgh, 201 US 161, 178-79 (1907).

For good measure, the Supreme Court doubled down on Dillon’s Rule in a 1923 case when it ruled: “A municipality is merely a department of the State, and the State may withhold, grant or withdraw powers and privileges as it sees fit. However great or small its sphere of action, it remains the creature of the State exercising and holding powers and privileges subject to the sovereign will.” Trenton v. New Jersey, 262 US 182, 187 (1923).

Perceptive readers might point out that a handful of states have passed what are called “home rule amendments” in order to specifically grant city governments some rights to local self-government. The Ohio Constitution, for example, declares:

“Subject to the requirements of Section 1 of Article V of this constitution, municipalities shall have authority to exercise all powers of local self-government and to adopt and enforce within their limits such local police, sanitary and other similar regulations, as are not in conflict with general laws.” Article XVIII, Section 3.

The key here, however, is the last part of the Amendment that limits local self-government to laws that “are not in conflict with general laws.”

This means that, in Ohio, if the state government has already legalized injection wells, then city governments are precluded from passing laws that make them illegal. Most states have never enacted home rule or local self-government provisions, which means that local governments in those states have even fewer rights to local-self government than states which have passed these provisions, like Ohio.

Just as Congress has supreme power over Indian tribes, state governments have supreme power over city governments. Just as Congress can terminate an Indian tribe, state governments may terminate city governments. Just as Congress’ sovereignty trumps tribal sovereignty, state sovereignty trumps municipal sovereignty. Municipalities, as Debra White Plume correctly deduced, are, indeed, “white man’s reservations.”

How would Indian tribes and municipalities gain true sovereignty?

How do we change all this? How would tribes truly gain sovereignty? How would city governments truly gain the right to local self-government? The harsh truth is those who benefit from the way American government is structured – the federal government, state governments, corporations, and large landowners – will viciously oppose any effective efforts to give tribes and city governments true sovereignty. Capitalists benefit from business friendly legal doctrines and a uniform regulatory system where they do not have to contend with patchwork prohibitions and restrictions enforced by sovereign communities. The entire American real property system is built on land stolen from Native peoples and would collapse if that land was returned to Native peoples. Empowering municipalities to reject harmful corporate projects would upend the legal mandate to maximize shareholder wealth. Judges and politicians are fully aware of this. And, they’re not going to be persuaded to change the dominant power arrangement.

The good news is persuasion is only one way to create change. Force is another. Force can, but does not have to, be violent. Power is not monolithic. What that means is those in power depend on us, depend on our obedience and cooperation to wield power. We can refuse our obedience. We can refuse to cooperate. Unfortunately, those in power can easily overwhelm isolated pockets of resistance. A few tribes, here or there, standing up for true sovereignty will be overpowered. A few municipalities, here or there, standing up for true sovereignty will be swatted down. For tribes and municipalities to gain true sovereignty non-violently, a mass movement of hundreds of tribes and municipalities must form, must refuse to comply with governmental, court, and police orders, and must put their sovereignty into practice.

At the end of the day, true sovereignty exists in the power of a community to physically enforce their sovereignty. The United States has supreme power over Indian tribes because the United States can send more soldiers, with more advanced weapons, to force Indian tribes to comply. The same is true for municipalities. So, if Indian tribes and city governments are serious about protecting their communities, they’ll need to learn how to counter the raw force the federal government can bring to bear. There is strength in numbers. And, if Indian tribes and municipalities saw themselves as the natural allies they truly are, they could join together to support and protect each other’s sovereignty.

Bio: Will Falk is an attorney. He co-founded Protect Thacker Pass and works with the Community Environmental Legal Defense Fund.