On a rainy August night in 1800, slaves huddled in small groups on plantations near Richmond, Virginia, waiting for a signal to rise up. Led by a slave named Gabriel, and comprised of close to a thousand slaves armed with tobacco-cutting scythes, the insurrection planned to seize Richmond’s armory, capture Governor James Monroe, and then ransom him in return for the slaves’ permanent freedom.

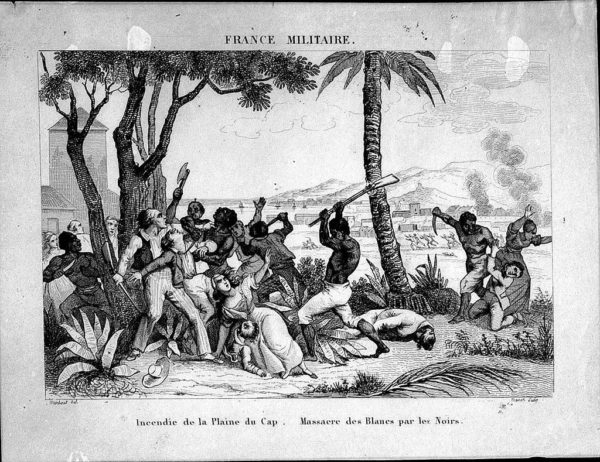

Gabriel’s rebellion wasn’t the first organized slave insurrection in the United States, nor would it be the last. Twenty years after Gabriel’s insurrection was cut short by a rainstorm that swept away key bridges between plantations, Denmark Vesey, a former Charleston slave, would lead an equally ill-fated revolt of thousands of slaves. Their plan was to burn Charleston, escape on a ship captured from the harbor, and flee to Haiti – the only place on the globe where a slave revolt had succeeded in seizing a colony from plantation owners.

http://beansouptimes.com/haiti-independence/#sthash.JeWdQa3u.dpbs

These insurrections were energized by new freedom movements sweeping the Atlantic. As summarized by historian Patrick Rael in his Eighty-Eight Years: the Long Death of Slavery in the United States, 1777-1865, the revolutionary radicalism of the American Revolution, as well as revolts fueled by that radicalism in Haiti, St. Domingue, Puerto Rico, Cuba, Martinique, and elsewhere, bolstered a new generation of slave insurrections in the U.S. As evidence of those direct links, Gabriel’s band of slaves adopted the slogan “Liberty to Slaves,” while Vesey’s rebellion was to begin on Bastille Day, in celebration of the French Revolution’s ending of slavery in the French colonies.

Both revolts were followed by harsh retribution – Gabriel, Vesey, and several hundred slaves were hunted down and hanged. Shortly after, the Virginia legislature passed a law requiring newly emancipated slaves to either leave the state or be re-enslaved, and laws were passed in Charleston requiring all black sailors docking in the city to be imprisoned for the length of their stay.

Without the slave revolts as a spark, abolition would have been rendered impossible.

Given the overwhelming strength of state and local militias, of course, slave insurrections in the American South were doomed to fail. As Rael writes, “(S)lave rebellion was a risky, all-or-nothing gamble. Its chances of success were minuscule, and the inevitable response to failure was even greater repression…from within, slave behavior might shake the foundations of the institution, but alone it was insufficient to destroy them.”

As noted by Rael, the permanent destruction of the slave system required white northerners to join with freed and enslaved African-Americans to build a broader Abolitionist movement. Without the slave revolts as a spark, abolition would have been rendered impossible.

A Contemporary Revolt: the Community Rights Movement

Beginning in the late 1990s, people in rural communities – being targeted by agribusiness and other corporations – began to ban factory farms, toxic waste dumping, water pumping operations, and other corporate projects. In places like Belfast Township, Pennsylvania, Barnstead, New Hampshire, and Shapleigh, Maine, people began doing what they had been told for over a hundred years that they could not do – adopt municipal laws to stop harmful corporate activities.

The rule of law under which municipal communities cannot stop corporate projects as long as those projects comply with state and federal law, is built from several legal doctrines manufactured by the same corporations protected by those doctrines. Those doctrines include the protection of corporations with constitutional “rights” and the punishment of municipalities who interfere with those rights, as well as the outright authority of state and federal governments to nullify municipal laws.

Check out Matt Wuerker’s political cartoons here: http://www.politico.com/wuerker/

Thus, the people who run corporations have a menu of options at their disposal to eliminate lawmaking that “interferes” with corporate prerogative. They may either use state legislatures to adopt new laws preempting and nullifying local laws, or they can use their own corporate “rights” to get a court to overturn the local laws (or they can do both). Because of that corporate power, and the authority of corporations and higher levels of government to preempt and nullify community-enacted laws – local laws aren’t laws at all, but mere suggestions to corporations regarding how and whether they should operate in a community. In many ways, they only have weight if corporate executives voluntarily agree to abide by them.

Stripping communities of the legal authority to stop corporate projects not only supplants people’s ability to decide the future of their municipality, it replaces it with corporate authority imposed from outside the community. Thus, communities stopped from saying “no” to big box stores are automatically prevented from building vibrant, sustainable downtowns; communities unable to say “no” to corporate factory farms are prevented from building and supporting small-scale, sustainable agriculture; and communities unable to say “no” to gas fracking operations are prevented from protecting clean water and breathable air.

Lacking the authority to decide what happens, communities are transformed into mere resource colonies.

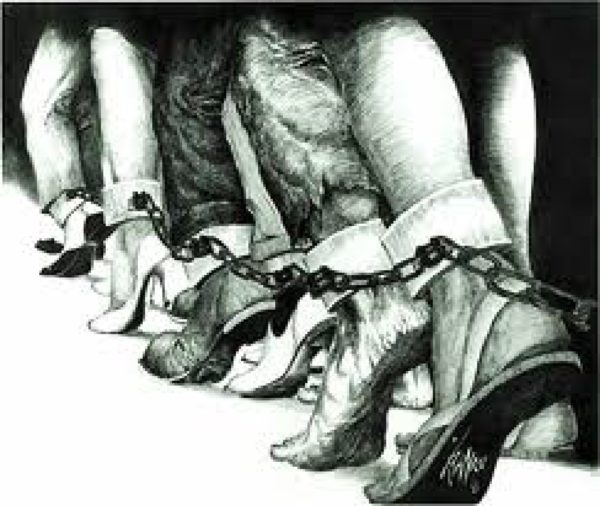

Lacking the authority to decide what happens, communities are transformed into mere resource colonies, with the people within them converted into squatters on their own land, relegated to enduring whatever the corporation chooses to give them.

The “Slave State” Transforms into the “Corporate State”

Just as the Abolitionist community was faced not just with the behavior of individual slaveowners, but with a system of law that protected the practice of slavery, communities today are faced not just with the behavior of individual corporations, but with a system of law that insulates corporate power from democratic control.

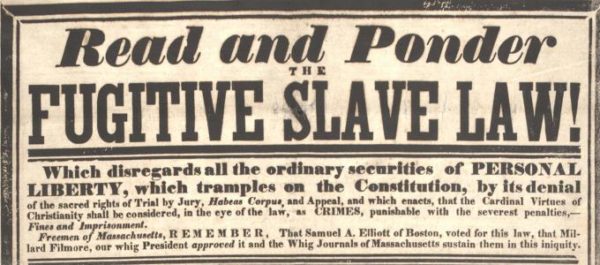

In the 1800s, slaves and Abolitionists confronted a system of law which placed the federal army at the disposal of slave states to put down slave insurrections. It was a system that counted slaves as three-fifths of a person for congressional representation while failing to recognize slaves as legal “people.” The very structure of the U.S. Constitution handed control of the federal government over to southern slaveholding states, while recognizing slaves as the right-less property of slaveholders.

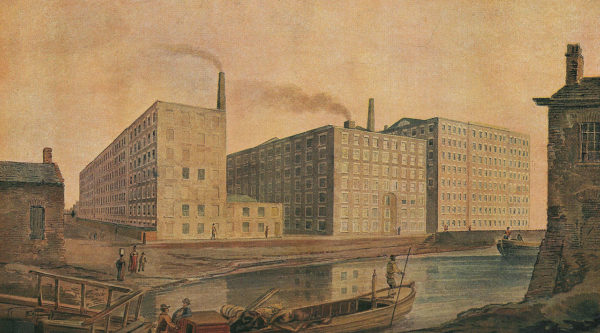

Aligned with that political power was national economic power. Northern banks and textile corporations amassed enormous fortunes from the southern cotton trade, New England shipping corporations were heavily invested in the slave trade, and early agribusiness corporations made fortunes from the growing and shipping of food to plantations in the West Indies.

“McConnel & Company mills, about 1820” A Century of fine Cotton Spinning, 1790-1913. Licensed under Public Domain via Commons – https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:McConnel_%26_Company_mills,_about_1820.jpg#/media

Thus, slaves, free blacks, and white Abolitionists faced off not just against the behavior of individual slaveowners, but against a governmental and economic system engineered specifically to support and protect the system of slavery. In the words of historian Richard Grossman, the system created and maintained a “slave state” in the U.S., in which governing power was held by those invested in the business of slavery.

While the U.S. Constitution enabled the enslavement of millions, in a more general sense, it afforded commerce the highest constitutional protections. The creation of the “commerce clause” within the Constitution – which bans local and state governments from directly regulating large areas of industry – can be directly traced to some of the wealthiest “founding fathers” who sought to prevent local and state governments from interfering with commerce and industry.

Those commercial protections, far from being destroyed by those who eventually brought down the slave state, morphed to protect newly rising industrial and commercial powers, now in the form of corporations.

Given that structure of constitutional protection, the recognition of constitutional rights for corporations by courts and judges wasn’t a mistake, but a natural evolution of the law. After all, if commercial rights were protected by the highest constitutional protections, why would those protections not be extended to the nation’s largest commercial actors, the corporations themselves?

Communities must defeat not just a single corporation, but a structure of law which elevates the “rights” of a corporation above the rights of the people who live within the community.

To stop harmful corporate projects, therefore, communities must defeat not just a single corporation, but a structure of law which elevates the “rights” of a corporation above the rights of the people who live within the community.

While slaves, free blacks, and Abolitionists faced off against the “slave state” of the 1800s – which had to be dismantled to free individual slaves – communities today must face off against a “corporate state.” The corporate state must, in turn, be dismantled to enable communities to not only stop harmful corporate projects, but to build economically and environmentally sustainable futures.

Slave Revolts & the Abolitionist Movement, Community Revolts & the Community Rights Movement

For the slave revolts to turn into a movement powerful enough to dismantle the constitutionally-enabled “slave state,” slaves had to join forces with scores of free blacks and white Abolitionists. Northern Abolitionists, for example, were able to leverage slave insurrections to undermine arguments by southerners that African-Americans were content to be enslaved. Further, they were able to show how a southern-controlled Congress could interfere with civil rights in the North – through the adoption by Congress of laws such as the Fugitive Slave Act, which required the imprisonment of northerners who failed to assist with the capture of escaping slaves.

http://tenthamendmentcenter.com/2014/05/20/constitutionally-sound-nullification-of-the-fugitive-slave-act/

While not putting their lives on the line, as slaves were forced to do, thousands of people today in close to 200 communities across the country have begun to liberate themselves from the “corporate state.” In small, rural communities like Grant Township, Pennsylvania, that has meant harnessing the power of their municipal government to adopt local bills of rights which ban frack wastewater injection wells, corporate factory farms, and corporate water withdrawals. Those municipal laws then elevate the rights of residents above the claimed “rights” of corporations, while openly rejecting the authority of the state and federal government to prohibit the community from banning those harmful projects.

As with the slave insurrections, these beachheads will not survive without the solidarity of thousands of other communities, and without the support of the broader political community – both liberal and conservative.

While professing to believe in local, grassroots, democratic control, and while understanding that environmental and economic sustainability is rendered impossible if decisions about local economies and the environment are able to be overridden by the very corporations seeking to exploit them, most mainstream groups have failed to support the growing movement for community rights.

http://www.wikihow.com/Save-the-Environment-(for-Teens)

Professional environmentalists within the “Big Green” groups – groups that held so much promise in the 1970s – have been at the forefront of steering communities away from challenging the existing structure of law and government. Because of that stance, it is those groups that now share more similarities with the corporations exploiting communities than with the communities themselves. Both are content to battle it out within regulatory agencies, where the ultimate decision has almost nothing to do with whether the community can reject corporate projects, but only with how the project will proceed.

Slaves, free blacks, and Abolitionists faced their own fox in sheep’s clothing – a group called the American Colonization Society. As with the big environmental organizations of today, the group was backed by prominent national figures including James Monroe, John Jay, and Daniel Webster. Buying land in Africa to relocate newly freed slaves, the organization touted itself as putting blacks “into a better situation” – away from the deep-seated prejudice against African-Americans that existed in the U.S. At the same time, the primary motive of the organization, as described by the group itself, was to “be cleared” of all African-Americans by shipping them overseas.

Rather than pretending that the Society had the same goals as the Abolitionist movement, leading white Abolitionists, like William Lloyd Garrison, called out the Society directly, accusing it of embracing the second-class status of African-Americans and perpetuating discrimination and prejudice. Eventually, under the onslaught of the free black community in the North and white Abolitionists, the American Colonization Society was forced to dissolve.

“Better regulation” of energy, agriculture, and transportation corporations only validates the authority of those corporations, and the highest levels of government, to continue on the same path.

A similar drive must be led to clear the landscape of big environmental organizations, whose goals are not the same as those working to recognize the legal authority of communities to reject harmful corporate projects outright. “Better regulation” of energy, agriculture, and transportation corporations only validates the authority of those corporations, and the highest levels of government, to continue on the same path. Unless we change out the decision makers, our march toward ecological destruction and the elimination of democratic self-government will continue to accelerate on its way off the cliff.

Lead, Follow, or Get Out of the Way

In response to slave insurrections in the South, in February 1834, students at Lane Seminary in Cincinnati sponsored a debate about whether slavery should be immediately abolished. In return, they were threatened with expulsion. In response, they withdrew and enrolled at Oberlin College where Ted Weld and a small band of a dozen others laid the groundwork for an evangelical Abolitionist movement which would eventually reach into churches, lofts, and schoolhouses across the North.

Today, the small band of communities taking on the world’s largest corporations have upped the ante, much as Weld and his brood did in the early 1830s.

Communities in seven states have now joined hands to create statewide community rights networks. Those networks are now proposing state constitutional changes which would elevate the rights of communities above those of corporations. They have also come together to propose a federal constitutional amendment which would recognize the legal authority of communities to ban harmful corporate projects and redefine corporate “rights” at the municipal level.

Colorado Community Rights Network http://cocrn.org/

It’s time to understand that the community rights movement is the movement that we’ve been waiting for – one not limited just to environmental issues, but one which can be used to advance indigenous rights, expand workplace rights, impose police accountability, challenge bank foreclosures, and establish rights to housing and healthcare.

Along the way, it promises to finally liberate us from the people that we’ve become – slaves in all but name.

http://www.ramblingrantsangryoldman.com/?p=157

Community Rights Paper #11: Slaves in all but Name

Visit here for more Community Rights Papers!